A new study illustrates in numbers what many already know intuitively: evangelicals aren’t big on dialoguing with anyone but themselves.

“Evangelicals seem to have a particularly difficult time talking to those outside their group,” the Barna Group reported in a March 9 study titled “Americans Struggle to Talk Across Divides.”

But Imam Imad Enchassi, spiritual leader of the Islamic Society of Greater Oklahoma City, said he has found many evangelicals to be very open to talking.

“I have encountered them right outside our mosque — with signs,” Enchassi said.

Signs like “turn or burn” and “Muhammad is a pedophile” are common, he said.

One Christian wore a hot dog costume to a protest, implying that standing close to Muslims is like being cooked over an open fire.

“I said ‘this is your best pick-up line for Jesus, really?”

Enchassi said he is optimistic, sometimes, during these encounters.

“I try to dialogue with them, but it’s basically a one-way street,” he said.

Difficult friendships

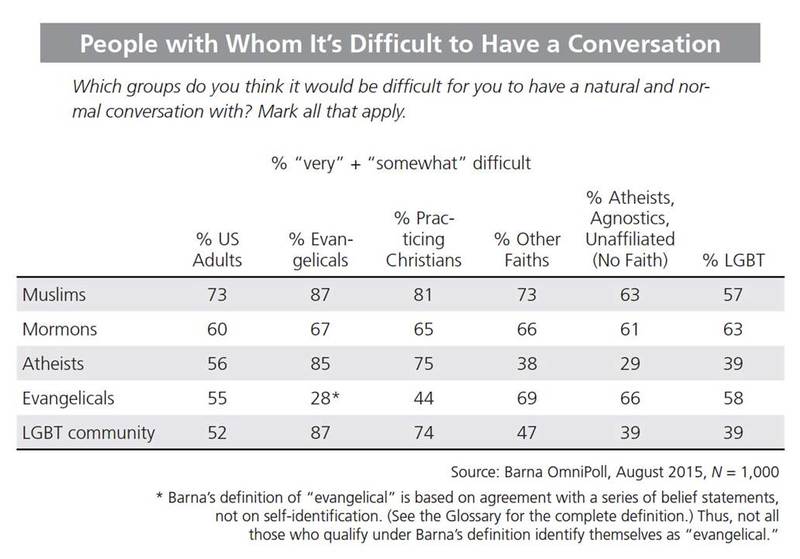

But Enchassi and other Muslims needn’t feel alone in that experience. The Barna data shows that while 87 percent of evangelicals avoid Muslims, the same percentage avoid members of the LGBT community and 85 percent won’t speak with an atheist. Nearly 70 percent avoid conversations with Mormons.

Other groups — including American adults as a whole, Christians, atheists and agnostics — also struggle with conversing with others, though not to the degree that evangelicals do, the Barna study reported.

A consequence is that few people can healthily engage with others unless they are in total agreement, Barna President David Kinnaman said in the report.

“Try to talk about things like gay marriage — or anything remotely controversial — with someone you disagree with and the temperature rises a few degrees,” he said.

“But being friends across differences is hard, and cultivating good conversations is the rocky, up-hill climb that leads to peace in a conflict-ridden culture,” he said.

But that seems to be an extremely up-hill struggle for evangelicals, which Barna defines as those who, among other things: have made personal commitments to Jesus Christ; believe the Bible to be accurate in all its teachings; feel compelled to share their faith with non-Christians; and believe salvation is possible only through grace, not works.

But that seems to be an extremely up-hill struggle for evangelicals, which Barna defines as those who, among other things: have made personal commitments to Jesus Christ; believe the Bible to be accurate in all its teachings; feel compelled to share their faith with non-Christians; and believe salvation is possible only through grace, not works.

‘Behold, I might be accused’

But it may be time to get a new term to define those Christians, others say.

“I just noticed a few weeks ago that I had stopped describing myself to people as an ‘evangelical,’” Russell Moore, president of the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, said in a Washington Post column titled “Why this election makes me hate the word ‘evangelical.’”

Moore laments the way the word is used by both Christians and non-Christians in the current election season, including reports that so-called evangelicals are supporting Donald Trump in large numbers.

So Moore said he has opted to identify himself as a “gospel Christian” instead.

Others suggest reclaiming the term for themselves.

“I like [pastor and author] Eugene Peterson’s great definition of evangelical, which is to believe the gospel of Jesus Christ can change someone’s life,” said Kyle Reese, pastor at Hendricks Avenue Baptist Church in Jacksonville, Fla. “I can go with that definition for myself.”

The Christians identified by the Barna study can also go by their traditional name, Reese said.

“In popular culture, evangelical is considered to be synonymous with fundamentalist Christianity,” said Reese, who is a leader in the interfaith movement in Northeast Florida.

The term makes sense in the current context because fundamentalists are long known for a guilt-by-association attitude toward speaking with non-fundamentalists, Reese said.

“If I sit down and have a conversation with someone, behold, I might be accused,” he said.

But there can be exceptions. Reese pointed out a conservative, non-denominational church located across the street from Jacksonville’s leading mosque. The two congregations have a close-knit relationship that is well known in the city.

“It’s a lot more difficult to hate someone and judge someone when they move in next door to do you,” he said.

‘Many important exceptions’

Muslim Parvez Ahmed said he has encountered evangelical Christians who defy the descriptions presented by the Barna study.

“This is not altogether surprising, true,” he said of Barna’s findings about evangelicals. “But let’s also keep sight of the fact there are many important exceptions.”

Ahmed is a Jacksonville resident also involved in that city’s interfaith community. He is also the former chairman of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, which has exposed him to Christian-Muslim relations at the national level.

Ahmed commended Moore as an example of an evangelical willing to dialogue with people of other faiths. He recalled that Moore and Saddleback Pastor Rick Warren were roundly criticized by conservatives for participating in Pope Francis’ marriage conference at the Vatican last year.

Ahmed said he’s encountered Christians, including Reese, who are staunch advocates of interfaith dialogue.

“There are some who have shown interest in the [interfaith] movement and who believe dialogue is consistent with the evangelical perspective of Christianity,” he said.

But there are also who don’t — and Ahmed has encountered them, as well.

Ahmed saw it first-hand after his 2010 appointment to Jacksonville’s Human Rights Commission. City Council meetings became scenes of anti-Muslim protests led by terrorism-fearing conservative Christians, including some members of the council.

One council member, a Southern Baptist, demanded Ahmed demonstrate a Muslim prayer from the podium.

Ahmed was eventually appointed to the commission, on which he still serves today.

Once, a prominent evangelical leader in Jacksonville asked for a meeting with Ahmed.

“I was very open to the conversation,” he said. “We met one time and after that he was not interested in meeting any further.”