Take a few hundred Nazis and Klansmen marching openly in Charlottesville, add three fatalities and a wink from the White House, and many people are apt to wonder if God is really out there.

“That’s a theodicy question: How can bad things happen to good people?” says Brandon Hudson, pastor at CrossCreek Baptist Church near Birmingham, Ala.

Those who feel disenfranchised in a social context usually wrestle with spiritual doubt, he says. The experience of repression naturally generates a loss of confidence in trust — or even belief — in God.

In other words, how can this be happening if a loving, all-powerful God exists?

“That’s the ‘why?’ question that’s always so difficult to answer.”

But new research reconfirms that doubt is nothing new and certainly not limited to catastrophe — cultural, political or otherwise.

Few seek guidance

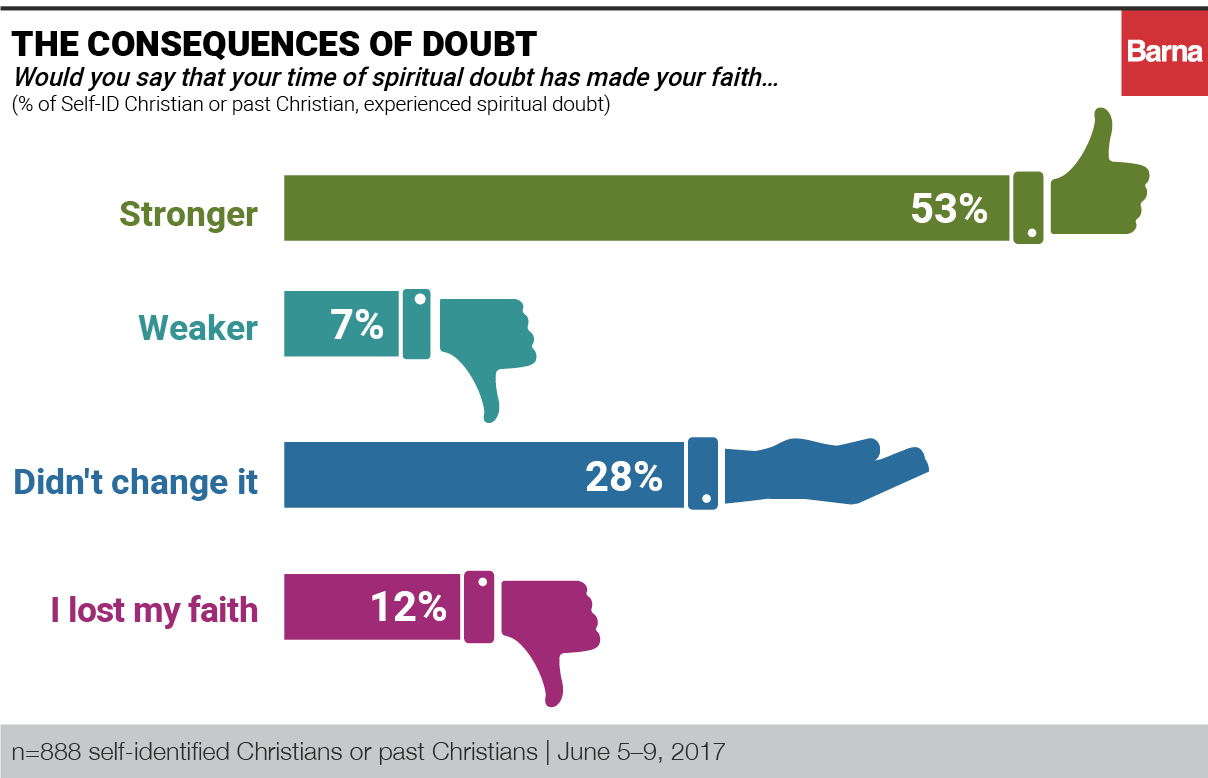

The Barna Group recently released a survey that asked U.S. Christians about their experiences with doubt. It found that the struggle is pervasive and often spiritually healthy. The study also found some disturbing trends, including an unwillingness by many to seek spiritual guidance from ministers or their churches.

The Barna Group recently released a survey that asked U.S. Christians about their experiences with doubt. It found that the struggle is pervasive and often spiritually healthy. The study also found some disturbing trends, including an unwillingness by many to seek spiritual guidance from ministers or their churches.

Barna researchers found that 40 percent of Christians in America have experienced doubt, and worked through it. Another 26 percent said they are currently experiencing doubt. About one-third reported to have never harbored doubt, Barna said in a summary of the report published online.

Among those identified as devout Christians, just under 20 percent said they have had spiritual doubt.

But most of those who have — 53 percent — said they have benefited from the struggle, Barna found.

“Among more devout groups who have experienced spiritual doubt, it overwhelmingly made their faith stronger.”

For others, wrestling with doubt resulted in ceasing worship attendance, Bible reading and prayer.A nd only 18 percent said they consult pastors or other spiritual leaders when they are questioning their faith, Barna said.

“The fact that so few would go to their spiritual leaders (or church, for that matter) may reflect the awkwardness of confiding in the individuals and institution that represent one’s questions, as well as the challenges that ministry leaders face to create safe spaces for doubt.”

‘Dark night of the soul’

That part of the survey, Hudson says, offered a particularly disturbing image of the church.

“Churches have become a culture where doubt is not welcome.”

That isn’t the case at CrossCreek, which has long embraced those who don’t have it all figured out.

“I say to my congregation from the pulpit that doubts are welcome here, that it’s OK to doubt,” Hudson says. “I am honest about my own struggles.”

Those doubts haven’t been about God’s existence so much as about why God isn’t working in the ways Hudson would like.

Those doubts haven’t been about God’s existence so much as about why God isn’t working in the ways Hudson would like.

“It usually comes across my plate when … I am confronted with change.”

Doubt, he adds, is not the opposite of faith but is intrinsic to it.

Erin Conaway, pastor at Seventh and James Baptist Church in Waco, Texas, agrees.

“As a kid, you believed everything you were told — until something happens. The questioning and the doubting, the moments of disbelief, are the things that help us grow.”

Scripture is replete with examples of people of faith, including Jesus’ disciples, working through periods of doubt, he says.

One of them was Mary Magdalen.

“Mary, she didn’t believe [the resurrection] even though she was standing in front of the risen Christ,” Conaway says. “She had been inside the tomb but still couldn’t make her mind and heart believe what her eyes were telling her.”

Knowing that she and other eye witnesses struggled with doubt should take the pressure off Christians beating themselves up for doing the same.

Conaway says he encourages others experiencing doubt to realize that it’s a natural part of the faith journey.

“The saints called it the dark night of the soul. You sense God’s absence over a prolonged time.”

It’s also important seek guidance, he says.

“We are created to exist in community. We are not supposed to go it alone, especially in times of doubt.”