By Bob Allen

A new book by a gay Baptist minister says it is time for churches to stop asking questions about whether homosexuality is right or wrong and begin listening to the voices of gays and lesbians who are sitting in their pews.

Cody Sanders, a McAfee School of Theology graduate and Ph.D. candidate at Brite Divinity School, says the church’s traditional stance has been “suspicious scrutiny” toward those who differ from the social or congregational norm.

Cody Sanders, a McAfee School of Theology graduate and Ph.D. candidate at Brite Divinity School, says the church’s traditional stance has been “suspicious scrutiny” toward those who differ from the social or congregational norm.

That suspicion prompts questions such as how someone can be both gay and a faithful Christian and whether or not LGBT persons should be allowed to join or lead churches and get married. With society’s increasing acceptance of homosexuality, he argues congregations should view them as instead a resource for learning about what it means to live as a Christian in an increasingly secular and pluralistic world.

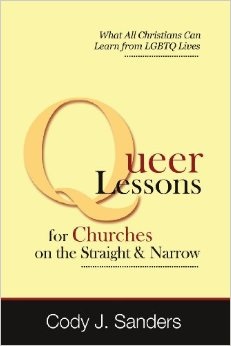

Queer Lessons for Churches on the Straight and Narrow: What All Christians Can Learn from LGBTQ Lives grew out of Sanders’ plenary address at “A [Baptist] Conference on Sexuality and Covenant” sponsored by Mercer University and the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship in April 2012.

Afterward Jim Dant at Faithlab — a firm in Macon, Ga., that provides creative services including web development and publishing for congregations and religious or non-profit organizations — approached Sanders about expanding the speech into a book “turning the questions we usually ask about LGBTQ people on their head to ask, instead, what churches should be learning from LGBTQ people.”

“As a queer person, I have grown tired of talking about sexuality — and my own life — on other people’s terms,” Sanders writes. “It is exhausting to answer the same old set of questions again and again. And it becomes utterly infuriating when you realize that the same people are asking these same questions relentlessly with seemingly little interest in any response that contradicts what they already ‘know’ about the subject.”

“As a queer person, I have grown tired of talking about sexuality — and my own life — on other people’s terms,” Sanders writes. “It is exhausting to answer the same old set of questions again and again. And it becomes utterly infuriating when you realize that the same people are asking these same questions relentlessly with seemingly little interest in any response that contradicts what they already ‘know’ about the subject.”

Sanders says it is time for churches to shift from their positions as “teachers” of often unwilling LGBT pupils to “attentive students” willing to learn from those who have been hidden, oppressed and silenced by sexual and gender privilege.

In a time when many people believe traditional marriage is in trouble, for example, Sanders says, heterosexual couples should wonder about same-sex relationships that endure despite legal barriers, religious disparagement and social disdain.

Similarly, he says, at a time when U.S. churches and denominations are losing members, “anyone attempting to beat down the doors to enter our houses of worship should raise our curiosity a bit.”

Not all the lessons are positive. One painful lesson that churches must learn, he says, is the violent potential of religion.

“It is certainly overly simplistic to say that religion causes violence against queer people,” he writes. “But it is both accurate and crucial for churches to confess the role that religious beliefs have held in fueling violence against queer lives. Our theologies have played a central role in cultivating a climate in which queer people regularly become the targets of violence.”

Sanders uses “queer” as an umbrella term to encompass a range of gender identities including “lesbian,” “gay,” “bisexual,” “transgender,” “sexually questioning,” “intersex,” “asexual” and others. But it’s also “a word of remembrance” of an epithet once used as a rhetorical weapon against those perceived as outside the norm.

“When we use the term — that is, when spoken by those of us who identify as somehow queer in our sexuality or gender identity – we are claiming a term once (and often still) used to enact violence against us, and reappropriating it as a term of unity and defiant pride,” he explains. “It is a movement of strength and resolve that says, ‘We won’t let you forever own this word as a term of contempt.’”