By Bob Allen

Religious liberty advocates say a case headed toward the U.S. Supreme Court Oct. 7 over whether Arkansas prison officials have the right to deny permission for a Muslim inmate to grow a half-inch beard for religious reasons is about far more than a fashion statement.

Numerous groups including Americans United for Separation of Church and State, the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty and the Southern Baptist Convention International Mission Board have all filed briefs urging the high court to overturn last year’s ruling by the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals that the Arkansas Department of Corrections grooming policy does not violate a federal law passed in 2000 requiring reasonable accommodation of religious exercise for Americans behind bars.

The Baptist Joint Committee, a Washington-based advocate for religious liberty and church-state separation representing 15 cooperating Baptist conventions and supporting congregations across the United States, chaired the Coalition for the Free Exercise of Religion, which helped pass the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act signed into law by President Clinton in 2000.

The law prohibits a state or local government from substantially burdening the religious exercise of an institutionalized person, unless the government demonstrates that imposition of the burden furthers a compelling governmental interest and is the least restrictive means available to further that interest.

Its passage came after the Supreme Court ruled in 1997 that a similar law, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, was unconstitutional when imposed upon the states. Passed in 1993 to restore religious liberties stripped by a 1990 Supreme Court decision over the religious use of peyote by Native Americans, RFRA was the legal basis for the recent landmark Supreme Court ruling that the federal government could not require the Christian owners of Hobby Lobby to buy employee insurance that covers methods of birth control that violate their religious beliefs.

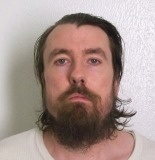

The case headed before the Supreme Court, Holt v. Hobbs, involves a request by Gregory Holt — also known as Abdul Maalik Muhammad — for an exception to the Arkansas Department of Corrections no-beard policy.

The case headed before the Supreme Court, Holt v. Hobbs, involves a request by Gregory Holt — also known as Abdul Maalik Muhammad — for an exception to the Arkansas Department of Corrections no-beard policy.

Sentenced to life in prison as a habitual offender for domestic violence and burglary, Muhammad says his Muslim faith requires him to grow a beard, contrary to the DOC policy allowing prisoners to wear trimmed mustaches but banning all other facial hair.

Prison officials say the policy is primarily for security reasons. They say beards make it easier for inmates to hide contraband and that an escaped bearded prisoner could disguise his identity quickly by shaving.

Briefs arguing on the prisoner’s behalf note that a vast majority of state prison systems allow members of religions including Sikhism, Islam and certain sects of Judaism to keep their beards for religious purposes. They also say Arkansas officials fail to explain why Muhammad’s request to grow a half-inch beard is significantly different from an exception already in the policy that allows prisoners to grow whiskers as long as a quarter-inch for reasons of dermatology.

Holly Hollman, general counsel of the Baptist Joint Committee, says the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act — typically abbreviated as RLUIPA — protects the right of people of all faiths to follow their religious beliefs.

“The government has a responsibility to ensure incarcerated individuals can freely exercise their religion if there is no contrary compelling governmental interest at stake,” Hollman said in an article on the BJC website. “This case demonstrates the need for RLUIPA to make sure religious rights are protected and taken seriously.”

The BJC brief, filed in May along with the American Jewish Committee, Union for Reform Judaism, Conference of American Rabbis and Women of Reform Judaism, says the case provides an opportunity to clear up disagreement by lower courts about what Congress intended when it allowed “deference” to institutional officials in applying the law when it comes to matters of prison security.

The brief says requiring prison officials to do no more “than simply say the magic words — safety and security of inmates and staff” — would render RLUIPA a “dead letter” when it comes to protecting a prisoner’s religious rights.

The SBC International Mission Board filed a separate brief with other religious bodies arguing that religious liberty “is a basic human right” that “extends even to the politically powerless, to the lawbreaker, and to those citizens whose religious practice may lie far outside the mainstream.”

Americans United for Separation of Church and State said in its brief that in accommodating religious exercise in prison, the state must not show favoritism to a particular faith. AU said Muhammad’s request for a “modest exception” to the grooming policy “imposes no meaningful burdens on any other inmate or anyone else and is materially indistinguishable from an exemption that is available to other inmates who request it for nonreligious reasons.”