More Americans say religion is increasingly influential in society even as faith’s importance on the personal level remains flat, according to new research by the Gallup Organization.

“The Religion Paradox” reported by Gallup also found that those active in faith are more likely to perceive religion’s rising dominance in American life compared to those less likely to self-identify as religious.

But some experts suspect the apparent contradiction may be exposing an American tendency to see religion as more relevant in times of trouble — such as during the COVID-19 pandemic.

That impulse was borne out in previous polling data and even by anecdotal observation in the aftermath of 9-11 and during the Great Recession, said Alan Rudnick, a Baptist minister, author and speaker who is working on a doctoral degree at La Salle University.

“The percentage of respondents who say religion is increasingly influential rose from 19% in December to 38% in April.”

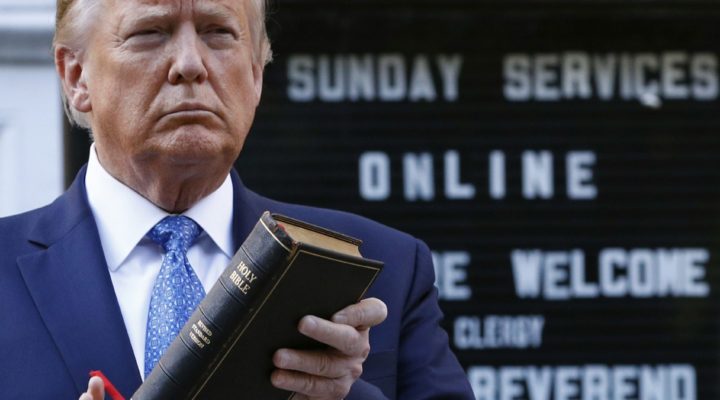

Recent images of President Trump posing with a Bible in front of a Washington, D.C., church, and news of religious groups’ Supreme Court victories also may be influencing Gallup’s findings, he suggested. “This puts religion and faith back into consciousness even for those who are not going to church and if they are not Christian. People are perceiving, whether it’s accurate or not, that religion is holding more influence in the public realm.”

Gallup reported that the percentage of respondents who say religion is increasingly influential rose from 19% in December to 38% in April.

“Despite the uptick in views that religion is increasing its influence in society, we don’t find evidence — yet — of an actual increase in the influence of religion at the individual level,” Gallup added.

The researchers noted that after 9-11, 71 percent of Americans perceived religion as more important than it had been. But similar conclusions can be drawn from both the 2001 terror attacks and the coronavirus.

Both crises “may deepen the faith of the already faithful, but there is no evidence that they widen the impact of religious faith on the population as a whole,” the study results said.

Greg DeLoach

The pandemic has uncovered “a tremendous chasm between religion and piety,” said Greg DeLoach, teaching pastor at First Baptist Church in Monroe, Ga., and interim dean at Mercer University’s McAfee School of Theology.

A rise in what DeLoach called “churchiosity,” the focus on the institutional facets of Christianity, may be contributing to the perception that religion is growing in significance during the pandemic, he said.

And the high-visibility relationship between government and religious conservatives is another factor, he added. “Civil religion seems to be in vogue.”

Even when there are resurgences of piety, they don’t last long historically, DeLoach recalled, citing the period immediately following 9-11. “People needed space to lament, to find hope and consolation. It was a really, really sweet moment in time. But then attendance went back to normal.”

DeLoach predicted this could happen again as Americans become accustomed to life in the pandemic and afterward. “I’m really questioning who is coming back.”

Alan Rudnick

The increasingly roving nature of American faith two decades into the 21st century may also be influencing the numbers, Rudnick said. “That spirituality is very nomadic, very seeking and very low in biblical knowledge.”

This development also may be traced to the latter years of the 20th century when the “spiritual-not-religious” concept began to take root, he said. “Americans began losing faith in their institutions in the 1960s and ’70s, and they lost faith in religious institutions as well. With that, the church lost its social capital.”

All this ties back into the perception of increased religious influence documented in the Gallup study, he added, suggesting it’s likely Americans assume the shows of faith on social and other forms of media indicate a genuine, wide-spread resurgence of faith.

“What we are seeing is a stream of episodic faith,” he said.

Another view, though, is that this paradox may result from the inherently difficult task of measuring personal piety or spirituality, said Julie Merritt Lee, a Houston-based Baptist minister who practices spiritual direction. “It is hard to measure spirituality, but spirituality is on the rise.”

Julie Merritt Lee

The pandemic has created a surge of interest in spirituality, she said. “People are coming out of the woodwork for spiritual direction.”

And no wonder, Lee added, as upheaval, grief, chaos and instability have inundated individual lives and families. “They are looking for ways to put the pieces together, and many are looking for spiritual ways to do that.”

So, it may be that measuring religion’s importance — whether public or private — is of limited benefit, she said.

“Maybe the levels of individual piety haven’t changed because they are measuring it by church attendance or some other external factors versus the longings of someone’s heart.”