In the midst of a turbulent summer of police violence against Black Americans, the pressure for institutional fixtures of American society to examine the legacies of their names never has been greater. Now the Southern Baptist Convention, according to the Washington Post, has begun considering changing its name to “Great Commission Baptists.”

Such a proposal finds itself situated within a long tradition of using 20th century branding techniques by American evangelicals.

J.D. Greear (Photo: Baptist Press)

On Sept. 14, J.D. Greear, current president of the SBC, announced that the 2021 theme of the denomination’s annual gathering would be “We Are Great Commission Baptists.” For the past eight years, the convention has used this moniker unofficially.

According to Greear, “Utilizing ‘Great Commission Baptists’ is simply one more step to make clear we serve a risen Savior who died for all peoples, whose mission is not limited to one people living in one time at one place. Every week we gather to worship a Savior who died for the whole world, not one part of it. What we call ourselves should make that clear.”

Current leadership in the SBC has concerns that the use of “Southern” in their name might send the wrong message, particularly to Christians of color. While the denomination was founded in 1845 after the Triennial Convention refused to appoint Southern slaveholders to the mission field, today 20% of the SBC’s pastors are persons of color and 63% of SBC congregations begun last year were led by persons of color.

The history of evangelical branding

Reporting from the Washington Post and Greear’s comments make clear that the denomination’s theology hasn’t changed. This move is about branding.

Historian Timothy Gloege argues that mass-marketing strategies and modern-day branding techniques became integrally intertwined with evangelical Christianity in the early 20th century. His book, Guaranteed Pure: The Moody Bible Institute, Business, and the Making of Modern Evangelicalism, shows the ways in which Moody Bible Institute branded itself to be one of the premiere evangelical institutions in the United States.

Historian Timothy Gloege argues that mass-marketing strategies and modern-day branding techniques became integrally intertwined with evangelical Christianity in the early 20th century. His book, Guaranteed Pure: The Moody Bible Institute, Business, and the Making of Modern Evangelicalism, shows the ways in which Moody Bible Institute branded itself to be one of the premiere evangelical institutions in the United States.

Henry Parsons Crowell first became a trustee of Moody Bible Institute in 1901 and quickly worked to secure the school’s financial footing. He did this, Gloege argues, by branding the nondenominational school as pure, wholesale gospel.

While denominational institutions teach a gospel weighted down by partisan theological and ecclesiological particularities, Moody Bible Institute under Crowell’s leadership claimed to teach a pure, unadulterated gospel free from denominational trappings.

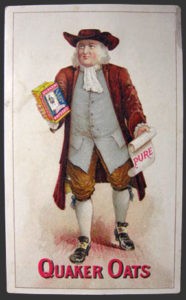

Crowell was not reinventing the wheel with this technique either. Prior to his time serving as trustee of the Chicago school, Crowell developed the now-famous marketing strategy for Quaker Oats. As Gloege writes, “The oatmeal market suffered under the weight of too many competitors, with prices often falling below production costs.” Crowell sought to differentiate his product from others through advertisements featuring a jovial Quaker oat man.

Consumers could rest assured that they were receiving a quality product because of the Quaker name. The original Quaker pitchman held a scroll upon which was written a single word, “Pure.”

Consumers could rest assured that they were receiving a quality product because of the Quaker name. The original Quaker pitchman held a scroll upon which was written a single word, “Pure.”

Crowell’s eye for marketing, Gleoge argues, proved effective in making not only Moody but also the larger evangelical and fundamentalist movements what they are today.

The move to consider changing their name to Great Commission Baptists functions as an extension of the long narrative of evangelical contemporary branding and marketing strategies.

A trend already happening

Many individual congregations within the denomination have already removed Baptist from their names or even begun from scratch without a denominational identifier. Rick Warren’s Saddleback Church in Southern California and David Platt’s McLean Bible Church in Virginia are good examples of this. Congregations like City Church in Tallahassee, Fla., can be difficult to identify as a Southern Baptist congregation.

For a conservative denomination like the SBC to change its name right now carries both potential reward and risk. Marshall Blalock, pastor of First Baptist Church of Charleston, S.C. — the oldest Baptist church in the South — explains the risk: “Anybody who knows why we’re trying to do this knows we’re not trying to be woke, and we’re not trying to cover up the past.” Instead, he says, “We need to remove barriers.”

The upside is potential rebranding that would signal to Black Christians that they are welcome in the denomination, while signaling to white, Southern Baptists that the denomination remains committed to the same conservative theological tradition.

The upside is potential rebranding that would signal to Black Christians that they are welcome in the denomination, while signaling to white, Southern Baptists that the denomination remains committed to the same conservative theological tradition.

SBC leaders might pivot to explain that the change seeks to be more accommodating for member congregations who reside outside the American South. In many ways, “Southern” no longer reflects the current geographic makeup of the denomination. While such a consideration is important, denominational leaders would be lying if they claimed the racial subtext of this descriptor was not a driving factor in the proposed name change.

Facing up to history

John Onwuchekwa, a Black pastor of Cornerstone Baptist Church in Atlanta, has been frustrated with the SBC’s strong support for President Trump and recently announced that his church is leaving the SBC. He thinks a name change might force the convention to face its history.

While some scholars point to the SBC’s 1995 apology over its complicity in slavery and racism as evidence of the denomination’s confrontation with its past, few acknowledge that this apology followed a similar statement by the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship in 1992. And even fewer acknowledge that this statement followed a similar statement adopted by then Southern Baptist Alliance (Alliance of Baptists) in 1990. These statements, while significant, did not rise to the appropriate level of reorienting each denomination’s relationship to white supremacy and racism.

For the SBC to make meaningful change in its relationship to both its history as well as contemporary communities of color, more is needed than a rebranding. Theological and ethical commitments must be interrogated and changed to root out the sins of racism and white supremacy.

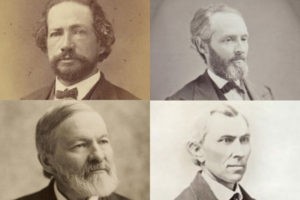

Southern Seminary founders, clockwise from top left: Boyce, Manly, Williams, Broadus.

Even now, intense debates rage among SBC leaders over how to make such institutional change, illustrated by the reluctance of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary — the SBC’s oldest seminary with ties to First Baptist Charleston — to remove the names of slaveholder and Confederate founders from its buildings.

Few institutions that have done the difficult work of changing the names of buildings and removing statues performed these actions in a vacuum. Instead, these changes have occurred in tandem with historical study and were accompanied by guidelines and practices for the future. Greear is providing leadership in this area, but he should look to other organizations and institutions as a guide. Simply rebranding the denomination’s name will not result in long-term change.

Moderate and progressive Baptists, pay attention

Greear’s leadership within the SBC provides an opportunity for moderate and progressive Baptists also to reconsider questions of congregational and even denominational name changes. Branding is a powerful tool, and not one to be taken lightly. In the 21st century, branding and marketing are essential for broadcasting your mission and identity to the world.

For moderate and progressive Baptists, the question often revolves around whether or not to keep the name “Baptist,” and if so where to place that title in the name — as in the case of River Road Church, Baptist in Richmond, Va.

Branding, however, is not and cannot replace the work of the church. Before considering whether a congregation needs to undergo a rebrand, congregations might consider finding new ways to serve their local communities. Before thinking about their names, churches might ask: What ministries do we perform for our community that provide opportunities for non-members to join in service? What work do we do that would beckon people to come and follow? What is our own history on racial issues? What is our congregation’s reputation in the community among people who don’t look like us?

In a world increasingly gilded — covered in a deceptively thin layer of gold — congregations have an obligation to be communities of character and depth. If rebranding is only intended to get more people in the pews on Sunday morning (or in today’s world more people on Zoom) your congregation may be gilded too.

Andrew Gardner holds a Ph.D. in American religious history and is the author of Reimagining Zion: A History of the Alliance of Baptists.

Andrew Gardner holds a Ph.D. in American religious history and is the author of Reimagining Zion: A History of the Alliance of Baptists.

This article was made possible by gifts to the Mark Wingfield Fund for Interpretive Journalism.

Related articles:

‘Disremembering’ our history: Pastor John Onwuchekwa, the SBC and the rest of us