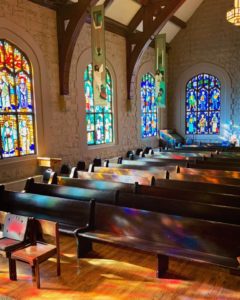

Anyone entering the sanctuary of Highland Baptist Church in Louisville, Ky., for the first time will inevitably leave talking one thing above all — the beauty of the stained-glass windows on all sides of the English Gothic-style worship space.

Look closely, though, and you’ll find in those colorful windows a source of the black-and-white problem that has sparked intensive congregational introspection that some hope will lead to public repentance: Two of the historical figures portrayed there were slaveholders and defenders of slavery.

Although the sanctuary was built in 1915, the stained glass was not installed until the 1970s — long after Louisville had been plunged into racial tensions and Southern Baptists (as Highland was then affiliated) were wrestling with how to respond.

The figures in those windows encapsulate both the history and the challenge facing a congregation known nationally for its progressive stances on women in ministry, social justice and LGBTQ inclusion. After pausing to take stock of its own story, a special task force of the church has found a gaping hole in the church’s history of progressive theology and inclusion: It has been profoundly silent about the racial divide that permeates the city and the church’s own history.

The figures in those windows encapsulate both the history and the challenge facing a congregation known nationally for its progressive stances on women in ministry, social justice and LGBTQ inclusion. After pausing to take stock of its own story, a special task force of the church has found a gaping hole in the church’s history of progressive theology and inclusion: It has been profoundly silent about the racial divide that permeates the city and the church’s own history.

That task force spent months researching the church’s history — from before its founding in 1893 to the present — and documenting what was said and not said, what was done and not done and laying that against the city and the nation’s history. The task force produced a 55-page report that has been used in two all-church dialogues and will guide next steps in what has come to be known as the church’s reparations project.

From stained glass to strained history

Nancy Goodhue is a lay leader at Highland who chairs the Reparations Task Force. In 2020, amid the nation’s racial reckoning ignited by the police shooting of Breonna Taylor in Louisville, followed by the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Highland members began asking more questions about their church’s potential complicity in the nation’s and the city’s history of racism.

Louisville, which lies along the southern edge of the Ohio River, is the epitome of a border city. Its architecture, culture and even its churches bear the influence of both North and South. The river itself was considered the visible expression of the invisible Mason-Dixon Line during the Civil War.

Basil Manly Jr. (Photo/Boyce Library/Southern Seminary)

Highland Baptist’s history is intertwined from the beginning not only with the aftermath of the Civil War but with the complicated racial history of the Southern Baptist Convention. The SBC’s first and now flagship seminary, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, is located just 2 miles up the road. And one of the seminary’s founders, Basil Manly Jr., was instrumental in starting the church.

Southern Seminary in 2018 issued a report on its historical ties to slavery and racism but its leaders declined to take any significant action or consider any kind of reparations. They refused to rename buildings on campus named for slaveholders and defenders of slavery as an institution. While that decision satisfied the conservative base that now controls the seminary, it rankled the more progressive crowd — including Highland members — now estranged from the seminary and the SBC.

All that hung in the background as the church’s Anti-Racism Team, formed in 2016, created a special subgroup to consider the windows. But before that project could be tackled, Goodhue went to other church leaders to suggest they needed to expand the scope of the work beyond the windows.

Highland’s congregation is highly educated and socially aware, and members began to connect the dots between the racial reckoning of 2020, the array of books being published on reparations for slavery and how to be anti-racist, what had happened at Southern Seminary, and the church’s stained glass.

Soon the Anti-Racism Team was joined by the Reparations Task Force.

Tell the history first

The predominantly white congregation asked for help from Black faith leaders in the community. Goodhue recalls that one of the recurring pieces of advice they were given was to “look at your history first.” The Black leaders told them: “You’ve got to look at your history and take it seriously and deal with it.”

Lauren Jones Mayfield

To that end, the task force began researching and writing. Goodhue suggested that a separate group of church members be enlisted to pray specifically for this work. Lauren Jones Mayfield, an associate pastor working with young adults and missions, has been running point on the entire reparations project. She pulled together a group of 10 prayer volunteers.

“One of the pleasant surprises was how nourishing it was,” she reported.

Mayfield believes that in addition to the prayer support, the congregation had been prepared also by the influence of its previous pastor, Joe Phelps.

“He was involved in several groups dealing with racial justice. He was preaching and calling awareness to the issues with the congregation,” she noted. He left the pastorate about three years ago, and his successor, Mary Alice Birdwhistell, arrived in Louisville from Texas just as the task force was being formed.

Birdwhistell, a native Kentuckian, embraced the project and blessed it.

When the task force released its report to the congregation earlier this fall, it scheduled two types of gatherings for church members to process the information together and ask questions. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the first of those was conducted via Zoom.

Not only did congregants ask questions, they also pointed out things missing from the written history. The task force took that information and revised the report.

Mary Alice Birdwhistell

While the individual parts of the story made sense, the combined effect of the narrative was “jarring,” Birdwhistell said. “It’s one thing for histories to be hypothetical or to be about ‘those people,’ but another thing to come to the realization that this is our history.”

“This work unearths some things within you and within your congregation that you’re going to have to wrestle with,” she added. “You’ve got to come to terms with your own complacency.”

The story that emerged challenged the way the progressive congregation thinks about itself, Mayfield added. “For all the ways Highland has shown up on issues, we have struggled to show up for the racial conversation.”

Failure to ‘show up’

Indeed, a recurring theme of the report is to note how when pivotal events were taking place in American history, Louisville history or Baptist history, the 128-year-old church seems to have been focused on other things.

That includes the spring of 1961, when Martin Luther King Jr. addressed students at Southern Seminary, calling them to join the work of racial justice and reform. The church’s records show no significant response or changes resulting from King’s speech even though seminary President Duke McCall — a former Highland member — was threatened by white pastors for allowing King to speak.

The narrative also explores a series of key junctures in the city’s history, from segregation to Jim Crow, to housing discrimination and redlining, to school integration and busing. Even though individual church members were living with and addressing these contemporary issues, there is only occasional evidence that the church was addressing them from the pulpit or in any other way.

“For all the ways Highland has shown up on issues, we have struggled to show up for the racial conversation.”

The few occasions where evidence of a response is recorded are notable mainly for their rarity. For example, in February 1946 the church held an “Inter-racial Sunday” which was followed the next Sunday night by a local Black man being invited to “speak about the prominent Black scientist George Washington Carver, whom he knew personally, in the Sunday night Training Union Assembly.”

And like many Southern Baptist churches at the time, Highland opened its membership to a Black person in 1965 not to bring in local Black Christians but when a seminary student from Nigeria asked to join.

1916 photo of Highland Baptist Church Sanctuary

Repeatedly, even when records indicate various pastors preached or spoke or wrote about racial justice, there is no evidence much of anything resulted within the life of the church. Instead, the congregation was busy doing other good deeds.

The report cites this example: “Highland Baptist Church records contain no evidence of official church support or church member participation in the demonstrations and nonviolent protests that gripped Louisville in the 1950s and 1960s. During the 1960s Highland focused its ministry on the Highland neighborhood, starting a ministry to the local elderly and, with other area churches, a coffee house aimed at serving youth in the Highlands who were not part of a church.”

And then there are reports of racially insensitive actions taken within the walls of the church, even as it was considered a trendsetter on other social issues. In 1972 and again in 1973, the church held a “Slave Auction” to help fund the youth group’s summer trips.

Seeing through stained glass

Finally, the story comes back to the stained-glass windows.

In 1970, the church called Don Burke as pastor — someone who is remembered at Highland as a highly creative and energizing force. During his tenure, the church hired artist Robert Markert to create the sanctuary stained-glass windows. The task force reports that “the church left it up to Burke to select the people honored in the windows, and he chose biblical characters and figures from church history, including from Baptist history.”

In 1970, the church called Don Burke as pastor — someone who is remembered at Highland as a highly creative and energizing force. During his tenure, the church hired artist Robert Markert to create the sanctuary stained-glass windows. The task force reports that “the church left it up to Burke to select the people honored in the windows, and he chose biblical characters and figures from church history, including from Baptist history.”

There was debate about whether to honor Martin Luther King — who had been martyred seven year earlier — but the church chose not to include him. The only Black figure included among the dozens of people honored in the stained glass is the pioneer missionary Lott Carey.

Extraordinary thought went into the creation of the windows, so much that they move along the spectrum of the rainbow in their colors — red, gold, green, blue and violet — as Burke once explained, “enveloping the worshipers with the colors of the rainbow, reminding the believers that they are the objects of covenant love.”

Ten windows around the bottom of the nave illustrate Hebrews 12:1, “Wherefore seeing we also are compassed about with so great a cloud of witnesses, let us lay aside every weight, and the sin which doth so easily beset us, and let us run with patience the race that is set before us.” These windows depict “the apostles and representative saints who have preceded the church of the present,” Burke explained.

The windows include “women of the Bible” and “European saints” and “United States Baptists.” But only one Black person and two white slaveholders.

Yet the stained-glass story doesn’t end there. In 2008 and 2009, the church invited the artist, Robert Markert, to extend the “Cloud of Witnesses” theme to the Fellowship Hall. Among those honored in these new windows is Basil Manly Jr., the Southern Seminary founder who helped launch the church — and who also was a slaveholder and defender of slavery.

What to do now?

The three Highland leaders most involved in the reparations study are convinced of one thing for sure: They cannot take their historical review, place it in a file and do nothing more.

“We have hired five African American consultants who are leaders in the city of Louisville,” Mayfield explained. “They have divergent opinions. One of the things they did agree on is that now that we have the history report, we have to take some action steps. Otherwise, we’re no different than Southern Seminary to have done this work but not follow through.”

Birdwhistell highlighted some advice given by Lewis Brogdon, director of the Institute for Black Church Studies at Baptist Seminary of Kentucky: “This problem has developed over 400 years, and none of it will be resolved in our lifetimes.”

Birdwhistell highlighted some advice given by Lewis Brogdon, director of the Institute for Black Church Studies at Baptist Seminary of Kentucky: “This problem has developed over 400 years, and none of it will be resolved in our lifetimes.”

But that is no excuse for inaction, the pastor added. “We’re asking, What steps can we take to move the needle?”

For now, the task force has divided its work into four prongs: Confession and repentance; imagery and symbols; finances; advocacy.

Each prong presents its own challenges. For example, while the church clearly wants to engage in confession and repentance, Mayfield said, “we’re wondering to whom do we confess and what does it mean for a white church to have this service and publicize this service?”

And reparations — most often thought of as financial — likely will take the form of long-term commitments to the community, the three church leaders agreed. One of the things the report highlights is how infrequently and insignificantly the church in the past funded anything in Louisville that served non-white populations.

“We want to give on a regular basis from here on out to a Black organization where we don’t have any say in how it is spent,” Goodhue explained.

Although rich in history, the mid-sized congregation does not have extensive financial resources to draw upon, no endowments or additional properties to sell. Even the property it currently fully utilizes requires urgent updates to the antiquated heating and air conditioning system.

Mayfield explained: “We’re trying to figure out in the midst of focusing on our building … how do we start a capital campaign for an internal need while talking about this need beyond us?”

This is where the fourth prong of advocacy could make a difference, Goodhue added. “The fact that Highland doesn’t have a lot of money is one of the reasons we want to connect with other groups. One of the things we want to do is to advocate to the federal government and other levels too for reparations.”

This is where the fourth prong of advocacy could make a difference, Goodhue added. “The fact that Highland doesn’t have a lot of money is one of the reasons we want to connect with other groups. One of the things we want to do is to advocate to the federal government and other levels too for reparations.”

The three leaders believe the church’s reparations work will outlive any of them. “This is ongoing, lifelong work for us,” Birdwhistell said. “You can’t think in a year and a half you’re going to figure it all out and check it off the list. The task force can only work for a limited amount of time, but the work is ongoing.”

At Highland, the next big step is to talk about the stained glass. That churchwide conversation is scheduled for February.

While that will be a tough one, the three leaders are hopeful. “We love this church,” Mayfield said. “What a privilege it is to serve as leaders in this conversation. Even when it is difficult, Highland Baptist shows up as people of faith and hope believing that repair is possible.”

Related articles:

Southern Seminary won’t rename buildings but creates scholarships for Black students

Ideas for churches studying the need for reparations | Analysis by Andrew Gardner

5 reasons why reparations talk makes white people crazy | Opinion by Alan Bean

What to do if you unearth a history of slavery in your church, college or institution?