In the current sociology of American religion, there are two trends moving in opposite directions. The “nones” are growing in number, while among those who identify as Christian, varieties of fundamentalism are growing.

Religion researcher Ryan Burge recently summarized this contradiction: “American religion is polarizing. Yes, there are more nones than ever. But there are also larger shares of Americans who are fundamentalists, too.”

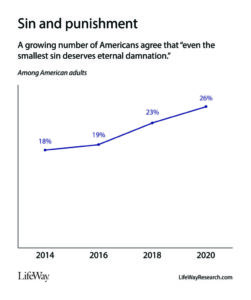

To illustrate, he posted a chart from a 2020 survey by Ligonier that found in America today 26% of people believe that “even the smallest sin deserves eternal damnation.” That number is up from 18% in 2014.

To illustrate, he posted a chart from a 2020 survey by Ligonier that found in America today 26% of people believe that “even the smallest sin deserves eternal damnation.” That number is up from 18% in 2014.

‘Fundamentalists’ versus ‘nones’

“Fundamentalism” has a specific meaning in American history, but the term also has become a broad brush for a collection of “conservative evangelicals,” another term challenging to define but widely thrown about.

It’s actually easier to talk about the “nones” than to quantify fundamentalists or conservative evangelicals, which partially explains why so many news reports appear fixated on the growth of the religiously unaffiliated.

Burge wrote the definitive book on the “nones” — published last year — and as both a Baptist pastor and statistician has keen insights into the opposing forces at work in America’s religious beliefs.

“Nones” are those who claim no religious affiliation. When asked on surveys which religious tradition they identity with, they check “none.” This includes not only the religiously unaffiliated but also smaller numbers of agnostics and atheists. But the growth among the “nones” comes almost exclusively from those who believe in God but just no longer — if they ever did — identify with a religious practice.

More growth among the ‘nones’

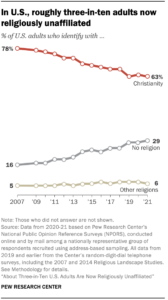

New data out this week from Pew Research shows the “nones” are continuing to grow in number — up 6 percentage points from five years ago and 10 points from a decade ago.

“Christians continue to make up a majority of the U.S. populace, but their share of the adult population is 12 points lower in 2021 than it was in 2011,” the Pew report says. “In addition, the share of U.S. adults who say they pray on a daily basis has been trending downward, as has the share who say religion is ‘very important’ in their lives.

“Christians continue to make up a majority of the U.S. populace, but their share of the adult population is 12 points lower in 2021 than it was in 2011,” the Pew report says. “In addition, the share of U.S. adults who say they pray on a daily basis has been trending downward, as has the share who say religion is ‘very important’ in their lives.

According to Pew’s numbers, today about 29% of U.S. adults identify as atheists, agnostics or “nothing in particular” when asked about their religious identity. Those self-identified as Christians of all varieties make up 63% of the adult population.

“Christians now outnumber religious ‘nones’ by a ratio of a little more than two-to-one,” the Pew report explains. “In 2007, when the center began asking its current question about religious identity, Christians outnumbered ‘nones’ by almost five-to-one (78% vs. 16%).”

The Pew data (acquired May 29 to Aug. 25, 2021) validate recent trends reported by all major surveys of Americans and their religious practices: The “nones” are growing, Protestantism in general is declining in adherents, and Catholics are barely holding steady.

Protestant trends

“The recent declines within Christianity are concentrated among Protestants,” Pew notes. “Today, 40% of U.S. adults are Protestants, a group that is broadly defined to include nondenominational Christians and people who describe themselves as ‘just Christian’ along with Baptists, Methodists, Lutherans, Presbyterians and members of many other denominational families. The Protestant share of the population is down 4 percentage points over the last five years and has dropped 10 points in 10 years.”

After a previous seven years of decline, the Catholic share of the population this year appears to have held steady, Pew says, with 21% of U.S. adults saying they are Catholic, identical to the Catholic share of the population in 2014.

But when the story turns to Protestant trends, the national data may appear conflicting. Particularly difficult these days is to define who is an “evangelical.” While survey takers have their methods, the very word “evangelical” has become fraught due to the large association of evangelical Christianity with Donald Trump and far-right politics.

When media reports cite statistics about “conservative evangelicals” believing this or are doing that, the reports usually are based in reality — the reality of a strong majority of that Christian population, sometimes up to 75% or more. Even a three-fourths majority, however, leaves a fourth of those who consider themselves “evangelical” wondering where they fit in.

The ‘evangelicals’

So who are these “evangelicals”?

Pew, for example, asks those surveyed whether they think of themselves as a “born-again or evangelical Christian,” a question likely to draw positive responses from those in Baptist and similar churches who might not hold other beliefs typically associated with being a culture-war evangelical.

Pew, for example, asks those surveyed whether they think of themselves as a “born-again or evangelical Christian,” a question likely to draw positive responses from those in Baptist and similar churches who might not hold other beliefs typically associated with being a culture-war evangelical.

Other surveys have shown that even those who fit a bona fide definition of a modern evangelical don’t answer questions in a consistent way.

The 2020 Ligonier survey cited by Burge noted: “While evangelicals tend to express great concern for the gospel, trends in our findings reveal that many evangelicals also express erroneous views that mirror the broader U.S. population. A substantial minority of evangelicals deny the deity of Jesus Christ, and many U.S. evangelicals exhibit confusion over who takes the initiative in God’s salvation of sinners. The latest survey shows a decline in the number of professing evangelicals who have an accurate understanding of the Holy Spirit’s work in salvation.”

What the data consistently show — and what the latest Pew research shows — is the widening gulf between an American culture that is less religious than ever and the extremely devout who attend church regularly but still may be confused about core biblical teachings.

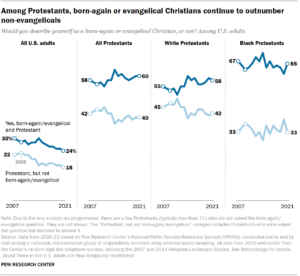

Pew reports that among American Protestants today, “evangelicals continue to outnumber those who are not evangelical. Currently, 60% of Protestants say ‘yes’ when asked whether they think of themselves as a ‘born-again or evangelical Christian,’ while 40% say ‘no’ or decline to answer the question.”

This pattern holds true among both white (58% evangelical) and Black (66% evangelical) Protestants, Pew says.

Largest and fastest-growing churches

What’s not true, Pew explains, is that all evangelical churches are growing or even that the total share of the population identifying as evangelical is growing. “Overall, both evangelical and non-evangelical Protestants have seen their shares of the population decline as the percentage of U.S. adults who identity with Protestantism has dropped. Today, 24% of U.S. adults describe themselves as born-again or evangelical Protestants, down 6 percentage points since 2007. During the same period, there also has been a 6-point decline in the share of adults who are Protestant but not born-again or evangelical (from 22% to 16%).”

“Among Protestants, born-again or evangelical Christians continue to outnumber non-evangelicals.”

Two important data points add interpretation to this:

First, from Pew, “among Protestants, born-again or evangelical Christians continue to outnumber non-evangelicals.”

Second, from other research we know that both the largest and fastest-growing churches in America tend to be conservative evangelical congregations. Outreach magazine publishes an annual list of the largest and fastest-growing churches in America, and that list consistently is populated by nondenominational churches and Baptist churches masquerading as nondenominational churches.

These largest and fastest-growing churches represent the core of the conservative evangelical base, and their pastors hold tremendous sway over large numbers of people. The Hartford Institute for Religion Research recently documented yet again that while the vast majority of churches in America are small, the vast majority of American churchgoers attend large churches: 10% of the nation’s churches attract 60% of regular churchgoers.

Declining piety

Amidst these disparities, the general trend line in American piety is downward.

Pew reports that fewer than half of U.S. adults (45%) say they pray daily. That is a 13-point drop from 2007. Further, 32% now say they seldom or never pray, up from 18% who said this in 2007.

Pew reports that fewer than half of U.S. adults (45%) say they pray daily. That is a 13-point drop from 2007. Further, 32% now say they seldom or never pray, up from 18% who said this in 2007.

Likewise, only 41% of American adults consider religion “very important” in their lives. That’s down 4 points from just a year ago and is “substantially lower” than all of Pew’s earlier data on this question. However, among self-described evangelicals, 79% say religion is “very important” in their lives.

Pew found that in 2021, 31% of American adults say they attend religious services at least once or twice a month, including 25% who say they attend at least once a week. These numbers are comparable to last year’s findings. Even among evangelicals, less than half say they attend services weekly. The only subgroup reporting more than 50% weekly attendance is Black evangelicals.

Related articles:

Largest-ever U.S. congregational survey confirms what church consultants have been telling you

Most comprehensive study yet of COVID’s impact on churches finds uneven results

Ryan Burge sifts the data to paint an evolving portrait of the ‘nones’