Writing from a Birmingham jail cell in 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. expressed his profound disappointment with “white moderates” who “constantly advise the Negro to wait for a ‘more convenient season.’”

We easily assume that, had we belonged to a Baptist Church in the mid-1960s, we would have plopped down proudly on the right side of history.

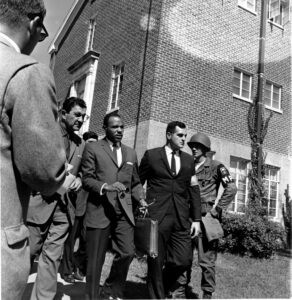

James Meredith, center with briefcase, is escorted to the University of Mississippi campus in Oxford. Escorting Meredith is Chief U.S. Marshal James McShane, left, and an unidentified marshal at right. (AP Photo, File)

A year before King wrote his letter in Birmingham, James Meredith sparked a deadly riot simply by showing up for class at the University of Mississippi. When Vivian Malone and James Hood followed Meredith’s lead the following year, Gov. George Wallace blocked the university door crying, “Segregation now! Segregation forever!”

But it wasn’t always that way. Wake Forest College (now University) integrated with comparative ease. The story begins, strangely enough, in New York City.

A missionary impulse

In 1958, James H. Robinson, a Black Presbyterian pastor from New York City, realized that unless missionaries joined the fight for African independence and were willing to add development work to their job description, the entire African continent might shut its doors to missionaries. His solution was to send teams of American students to African nations for six weeks during the summer. The first five weeks were devoted to hands-on labor in remote villages. The final week was reserved for a whirlwind tour of the continent.

Wake Forest’s G. McLeod (Mac) Bryan agreed and, in 1959, he made his first of 14 tours of Africa with Robinson’s Operation Crossroads Africa.

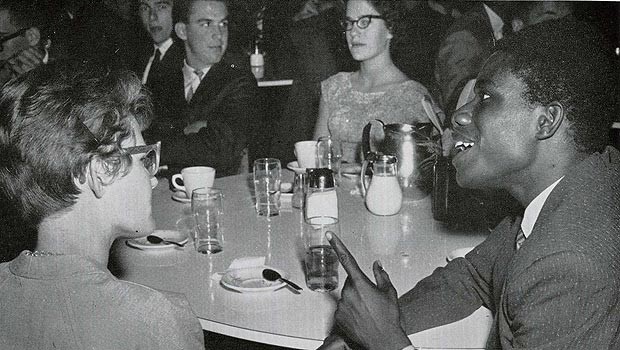

White patrons wave Confederate flags at Blacks sitting at the Woolworth’s lunch counter on Feb. 9, 1960. (Photo: Winston-Salem Journal)

Shortly after returning to Winston-Salem, N.C., Bryan prepared a small cadre of devoted students to participate in the series of revolving sit-ins that effectively shut down the city’s restaurants and lunch counters. In 1960, with Winton-Salem’s eating establishments integrated, the students decided the next step was the racial integration of Wake Forest College.

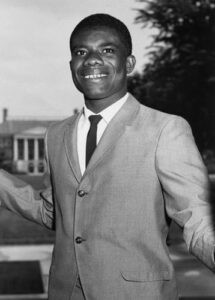

Ed Reynolds

Instead of sending American students to Africa, Bryan suggested, why not encourage African students to apply to Wake Forest. How could the college reject admission for a young man who had been won to Christ by Southern Baptist missionaries? Bryan reached out to Harris Mobley, a former student from Bryan’s days at Mercer College who was serving as a Southern Baptist missionary in Ghana. Mobley suggested Ed Reynolds, a Ghanian student with a keen desire to effect social change.

Initial rejection at Wake Forest

To cover Reynolds’ expenses, Wake Forest students and faculty organized an African Student Fund. When Reynolds the Ghanian arrived in 1961, Wake Forest rejected his application, arguing that he needed remedial work. Undeterred, the Ghanian enrolled in Shaw College, a Baptist, historically Black school in nearby Raleigh. In 1962, the Wake Forest administration relented and Wake Forest admitted its first Black student.

The following year, Harris Mobley encouraged Mercer College in Macon, Ga., to enroll another Ghanian, Sam Ricky Oni. Reynolds and Oni were just as committed to the civil rights struggle in the United States as they were to emancipating Africa from colonial rule.

Sam Oni with an unnamed students at Mercer University. Oni was the first Black student admitted to the all-white Baptist school.

Reynolds and Oni were presented as the fruit of the Southern Baptist mission project. If we can convert these men to our Christ, the argument went, surely we can admit them to our colleges. Besides, everyone assumed that African students would soon be going home, at which point, life might return to normal.

A second admission at Wake Forest

In 1963, William Rufus (W.R.) Ojo became the second African admitted to Wake Forest. In marked contrast to Reynolds and Oni, Ojo didn’t see himself as a change agent. He had been educated by an all-white faculty at the Baptist high school he attended in Nigeria, and Ira Newburn Patterson, Ojo’s high school principal, also served as general superintendent of the Nigerian Baptist Convention from 1944 to 1964.

In Fight!, his autobiography, Ojo makes no mention of the civil rights struggle that engulfed Winston-Salem during his student years. The Nigerian pastor focused exclusively on his studies and in writing letters to his wife, Grace, who wasn’t able to join him in America until 1965. Ojo was a decade older than Reynolds and Oni. He already had graduated from the Southern Baptist-sponsored seminary in Nigeria and led a church of more than a thousand people when he decided to further his education. The Nigerian Baptist Convention, not the African Student Fund, was footing the bill for his education.

A cold shoulder in Louisville

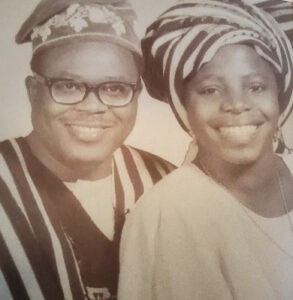

W.R. and Grace Ojo

When W.R. Ojo graduated from Wake Forest College in 1965, he and Grace spent a year in Louisville, Ky., When they started looking for a church, Lucy Ernelle Brooks, a Southern Baptist missionary in Nigeria, encouraged them to visit Highland Baptist Church where her brother, Nathan Cohn Brooks, was pastor.

After attending his first service at Highland, Ojo stood in line as Nathan Cohn Brooks welcomed worshippers on the church steps.

Highland’s pastor had earned a reputation as one of the most progressive pastors in the Southern Baptist Convention. According to a recent congregational history, he “was part of the interfaith, interracial ‘home visits’ program in which whites, Blacks and people of different faiths met in each other’s homes to talk about race, and he encouraged Highland members to join him.”

Highland’s pastor had earned a reputation as one of the most progressive pastors in the Southern Baptist Convention. According to a recent congregational history, he “was part of the interfaith, interracial ‘home visits’ program in which whites, Blacks and people of different faiths met in each other’s homes to talk about race, and he encouraged Highland members to join him.”

Five months prior to Ojo’s initial visit, Brooks had informed church leaders “that several Negro families live in our immediate church community,” and he had urged the congregation to “discover ways to minister to these families.”

But when Ojo finally arrived at the front of the line, pastor Brooks turned his back and began chatting with his parishioners. “It continued like that for a couple of weeks,” Ojo recalled. “I would wait for him to shake my hand, but he never did.”

Ojo was undeterred. A few weeks later, he responded to the invitation at the close of worship along with several white couples. Pastor Brooks introduced the white couples to the church and the congregation joyfully voted them into membership.

Brooks quietly asked Ojo to visit with him after worship. “He said it was beyond him to accept me because I was Black,” Ojo recalled, “and it could lead to the loss of some members of the church who did not favor people like me attending their church.”

The Nigerian pastor was stunned. “It was if I was dreaming. I went home that day feeling and looking dejected.”

“It was if I was dreaming. I went home that day feeling and looking dejected.”

Historical context

Brooks’ reaction must be placed in historical context. Beginning in 1963, Black students from Morehouse College began seeking admission to worship at First Baptist Church of Atlanta, then the largest church in the SBC. Told they could worship in the overflow room in the basement, the students dropped to their knees on the church steps, crying out for justice. If Morehouse students didn’t show up on Sunday morning, a contingent from Georgia Tech, or some other area school, would perform the same ritual.

A few of the church’s most enlightened members, most of them college students, soon were calling for the church to scrap its whites-only policy. Staunch segregationists defended traditional practice. A third contingent was willing, in theory, to consider a change of policy, but dismissed the protesters as attention seekers. When television cameras appeared to drink in the drama on Sunday mornings, white resentment multiplied.

A few of the church’s most enlightened members, most of them college students, soon were calling for the church to scrap its whites-only policy. Staunch segregationists defended traditional practice. A third contingent was willing, in theory, to consider a change of policy, but dismissed the protesters as attention seekers. When television cameras appeared to drink in the drama on Sunday mornings, white resentment multiplied.

Then Alton Jones, a white preacher committed to world peace and racial justice, showed up in company of two students, one white, one Black. Jones was told he could enter the sanctuary, but his Black companion could not. Jones turned to white worshipers streaming into the building and shouted, “Come right in, folks, worship a segregated God in a segregated church.”

Jones was arrested and charged with “disturbing public worship.” At trial, police officers testified to having been kicked, scratched and bitten by the 67-year-old preacher. Jones denied it. For one thing, he said, he was committed to nonviolent principles. For another, “my dentures won’t allow me to bite.”

At trial, police officers testified to having been kicked, scratched and bitten by the 67-year-old preacher.

Short months before pastor Ojo visited Highland Baptist Church in Louisville, the Atlanta congregation abandoned its commitment to whites-only worship. In announcing the policy change, Pastor Roy McLain made two things clear: First, allowing Black people into the sanctuary “does not mean you have to marry them.”

More rejection in Macon

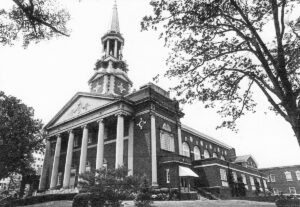

The religious controversy quickly shifted to Macon, Ga. When Sam Rickey Oni arrived on the Mercer campus in 1963, it was widely assumed that, like most students, he would be attending nearby Tattnall Square Baptist Church. Determined to quash that possibility, Tattnall’s senior pastor visited Oni’s dorm room and announced that Black people were not welcome in his church.

The religious controversy quickly shifted to Macon, Ga. When Sam Rickey Oni arrived on the Mercer campus in 1963, it was widely assumed that, like most students, he would be attending nearby Tattnall Square Baptist Church. Determined to quash that possibility, Tattnall’s senior pastor visited Oni’s dorm room and announced that Black people were not welcome in his church.

When Oni presented himself for membership at the nearby Vineville Baptist Church, pastor Walter Moore framed the issue for the congregation with great care. Oni was not “an ordinary local Georgia Negro,” he told the church. “He was a peculiar Negro … a unique Negro, one who had come to know the Lord through their own praying, their own gifts and their own efforts on the mission field.”

Oni was not “an ordinary local Georgia Negro,” the pastor told the church.

Late in 1964, Thomas Holmes accepted the pastoral call of Tattnall Square Baptist Church with the clear understanding that the congregation would swiftly move toward integrated worship. In 1965, Holmes pressed ahead with this agenda. It cost him his job.

An incensed Sam Jerry Oni strode up the front steps of Tattnall Square Baptist Church in the wake of Holmes’ ouster. As the television cameras whirred and the congregation sang “Where Cross the Crowded Ways of Life,” two oversized deacons dragged the Ghanian student from the church.

A call from Nigeria

These events were replaying in the mind of Nathan Cohn Brooks when he was confronted by pastor Ojo.

The Nigerian remained undaunted. He called up his old high school principal, Ira Newburn Patterson. Patterson contacted Lucy Brooks in Nigeria, and she implored her brother to change his mind. If word got out that a prominent Nigerian pastor had been refused membership by one of the SBC’s most progressive congregations, the Nigerian Baptist Convention would be outraged and Brooks would be in bad odor at Louisville’s Southern Baptist Theological Seminary.

According to Ojo’s memoir, “the pastor called and begged me to come to church the following Sunday.” At the close of worship, Brooks lectured his flock on the unity of Christ’s body and Highland Baptist Church was officially integrated.

Vintage postcard of Broadway Baptist Church

For a few months, all was well. Then Ojo mentioned to the faculty adviser of the seminary’s international club that, before returning to Africa, he wanted to spend a few months at the SBC Radio and Television Commission studios in Fort Worth, Texas. From Louisville, Professor James Leo Garrett called J.P. Allen in Fort Worth and asked him if Broadway Baptist Church was ready to welcome a Nigerian family.

Broadway’s deacons had discussed the matter in 1963 but failed to adopt a definite policy. Pastor Allen took the matter to his executive committee, they kicked it over to the deacons, who announced a congregational talking session. Finally, in a fourth meeting, the issue was put to a vote. The couple was asked to show up for worship in indigenous dress, and they happily complied.

Finally, in a fourth meeting, the issue was put to a vote. The couple was asked to show up for worship in indigenous dress, and they happily complied.

Everything went so smoothly that the integration of Broadway Baptist Church didn’t warrant a mention in Ojo’s autobiography. Presumably, the couple never learned of the frantic, behind-the-scenes negotiations that preceded their arrival.

It is easy to dismiss this history with a snort of bemused indignation. Why, we ask, were these Baptists of old so afraid to do the right thing?

But what would happen in your church if two women, or two men, walked the aisle hand-in-hand. Would your church respond with grace and joy? If not, Dr. King’s disappointment with white moderates abides.

Alan Bean is executive director of Friends of Justice, an alliance of community members that advocates for criminal justice reform. He lives in Arlington, Texas.

Related articles:

What to do if you unearth a history of slavery in your church, college or institution?

How the church in Maryland became the primary auction block for slaves

Racism and the evolution of Protestant support for private education | Analysis by Andrew Gardner