The American Civil War was “a war with a musical soundtrack,” according to Christian McWhirter.

And that soundtrack continues to echo through the American church today, illustrating the different life experiences of Black and white Christians in particular, once again “marching as to war,” as one popular hymn declares.

During the 19th century, music was everywhere. And while most history of the Civil War focuses on the details surrounding the conflict between the North and the South, very few have considered the role music played.

“Songs influenced the thoughts and feelings of civilians, soldiers and slaves — shaping how they viewed the war.”

“Although it was certainly a prominent part of Northern and Southern culture before 1861, the war catapulted music to a new level of cultural significance,” McWhirter writes in Battle Hymns: The Power and Popularity of Music in the Civil War. “More than mere entertainment, it provided a valuable way for Americans to express their thoughts and feelings about the conflict. Conversely, songs influenced the thoughts and feelings of civilians, soldiers and slaves — shaping how they viewed the war.”

The primary role of music was “connecting disparate listeners and performers to the broader conflict,” according to McWhirter, a Lincoln historian. “Some pieces did this explicitly through lyrics directly referencing various aspects of the war, but others were more subtle. Patriotic songs taught Americans how to interpret the politics of the war, while sentimental ballads helped them cope with the spectrum of emotions a large and costly military struggle could introduce.

The primary role of music was “connecting disparate listeners and performers to the broader conflict,” according to McWhirter, a Lincoln historian. “Some pieces did this explicitly through lyrics directly referencing various aspects of the war, but others were more subtle. Patriotic songs taught Americans how to interpret the politics of the war, while sentimental ballads helped them cope with the spectrum of emotions a large and costly military struggle could introduce.

“Songs also allowed listeners and performers to understand their roles in a war-torn society. It was in the popular songs that Americans balanced their personal and civic responsibilities. Patriotic songs told them where their allegiances lay, but sentimental songs addressed how those allegiances could affect their personal lives.”

Between blackface and benefits

During the war, minstrels in blackface became popular in the North as a way of influencing how white people in the North perceived Black people in the South.

In the Music in Art journal, Melissa Zapata-Rodriguez says: “It was during the Civil War that minstrel iconography fueled even more the racial disparity that enabled white society in the North to fall into conflicting ideas about African Americans. Northern white society in the United States was comprised of abolitionists (radical and conservative), moderates and racists. These discerning views played an important part in music production during the Civil War, especially on the minstrel stage. Both racial animosity toward African Americans and abolitionists efforts in the North would mark the confusing, and somewhat contradictory sentiment that white Northerners would maintain during the American Civil War.”

In the South, Black people often were paraded around to sing and dance in order to “show how ‘happy they were,’” which McWhirter notes was “the favorite theme of Southerners.” Many of these events were benefit concerts that featured slave musicians in order to raise money for the war.

Between battlefields and wash bins

One month after the Civil War began, the United States War Department announced that each regiment would be allowed to have a 24-member brass band. Two months later, the Union army required every regiment to have two musicians.

“Music has done its share, and more than its share, in winning this war.”

In The Civil War 100, Michael Lanning says the North had 28,000 musicians who played in 618 bands, prompting Union general Philip Sheridan to say, “Music has done its share, and more than its share, in winning this war.” Robert E. Lee added, “I don’t think we could have an army without music.”

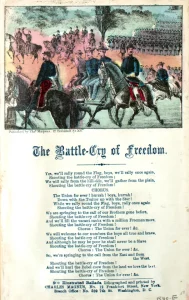

Even though music was key to everyone’s experience and processing of the Civil War, it evolved as the war developed. Songs toward the beginning of the war featured lyrics that emphasized recruiting soldiers to the cause. But as the armies filled their ranks, recruitment songs began to fade.

Even though music was key to everyone’s experience and processing of the Civil War, it evolved as the war developed. Songs toward the beginning of the war featured lyrics that emphasized recruiting soldiers to the cause. But as the armies filled their ranks, recruitment songs began to fade.

The most popular songs that emerged appealed to soldiers in battle. McWhirter says: “Pieces with melodies, lyrics and themes appealing to fighting men found the widest audiences. … In effect, soldiers became not only music’s most enthusiastic consumers but its most effective distributors.”

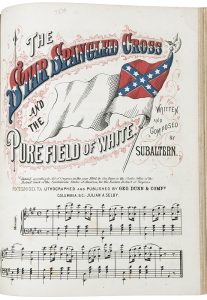

As the war came to a close, the bold singing of the Confederates began to waver.

McWhirter says: “At the end of the war, Confederates experienced a crisis of confidence in their music — finding that the sting of defeat transformed many of their favorite anthems from bold statements of purpose to dour reminders of a cause lost.”

Songs in secret

But while soldiers on both sides of the war strode onto the battlefields with songs of purpose and triumph accompanied by professional musicians, the songs of the slaves were experienced in secret.

“It was not Sunday morning worship with their masters that nourished the spirit of the slaves, but their secret meeting.”

In her book In Their Own Words: Slave Life and the Power of the Spirituals, Eileen Guenther says: “By and large, it was not Sunday morning worship with their masters that nourished the spirit of the slaves, but their secret meetings. … The meetings, held in secret places out of earshot of the overseers and owners, were times of genuine faith and ‘real’ worship — places of respite, protest, self-expression, creativity and building community.”

She continues: “This was the milieu from which the Spirituals emerged. … Locations varied: in a distant cabin, under a clump of trees, or in a distant gully… . Slaves risked punishment if they were caught in such meetings. Children might be stationed in tree tops as lookouts to whistle a warning should an overseer come close to their meeting place. Participants also hung wet quilts on overturned iron pots in order to mute the sound of their praying and singing.”

McWhirter says slaves responded to bans on singing by, “going to their cabins and singing with wash bins over their heads so (their master) could not hear them.”

McWhirter says slaves responded to bans on singing by, “going to their cabins and singing with wash bins over their heads so (their master) could not hear them.”

Between conquering and code

With the growing popularity of war songs, it is no surprise that hymns like “Onward, Christian Soldiers,” “Sound the Battle Cry,” “Stand Up, Stand Up for Jesus,” and “The Call to Arms is Sounding” resonated among white congregations during the second half of the 19th century.

White congregations sang such lyrics as:

Stand up, stand up for Jesus,

Ye soldiers of the cross.

Lift high his royal banner,

it must not suffer loss.

From victory unto victory

his army shall he lead,

till every foe is vanquished,

and Christ is Lord indeed.”

But gatherings of Black worshipers had to sing in code. Guenther details how slaves used songs such as “Follow the Drinking Gourd,” “Go Down, Moses,” “Gospel Train’s a Comin’” or “Wade in the Water” to signal to one another when rescue was coming.

“Code songs might seem harmless enough to owners or overseers but could convey to the slaves a hidden meaning, such as the time of a secret meeting, or the arrival of a guide to lead them to freedom,” she explains.

“Code songs might seem harmless enough to owners or overseers but could convey to the slaves a hidden meaning.”

The slaves also used a biblical code in their songs — with references to Egypt, Babylon or hell being metaphors for the South, references to Pharaoh or Satan being metaphors for their masters, references to Pharaoh’s army being metaphors for the patrollers, references to the Israelites as metaphors for themselves, references to Jesus as metaphors for those who would rescue them, references to the Jordan River as metaphors for their liberation, and references to the Promised Land as metaphors for the North, Canada or heaven.

And because white congregations mixed political war language with religious worship language, Black communities knew coded worship music would be allowed. McWhirter explains: “Blacks knew that plain talk about freedom and equality would surely meet with harsh disapproval or worse from white listeners, but song lyrics couched in religious imagery were acceptable and even endearing to whites.”

Between power and liberation

Like the children of Israel, African American worship was intrinsically connected to political liberation from empire. But for white Americans, worship was connected to conquest. And the war only exacerbated this.

“Religious music was long dominant before the Civil War and only became more so as the conflict progressed, especially in the armies,” McWhirter wrote.

“Religious music was long dominant before the Civil War and only became more so as the conflict progressed, especially in the armies,” McWhirter wrote.

One popular song among white people said:

Mighty Ruler, all commanding,

Reigning on thy heavenly throne,

Forth to earth thy spirit sending,

Winning conquests for thy Son,

Led our armies

till rebellion be cast down.

Even “The Star Spangled Banner” was sung in church services. McWhirter writes: “With ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ waving its way even into church services, some observers began to wonder if its lyrics adequately expressed the North’s wartime sentiments.”

Therefore, Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. wrote a new verse:

When our land is illumined with

Liberty’s smile,

If a foe from within strike a blow

At her glory,

Down, down with the traitor

Who dares to defile

The flag of her stars and the page

Of her story!

Songs written by white people sent mixed messages while continuing to evolve. For example, “John Brown’s Body” was born out of camp meetings hosted by Christians, then became popular with Union soldiers as a memorial to an abolitionist who had died and also as a coarse joke about a soldier in one battalion who had the same name.

But then the song was given new lyrics and was changed to “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” But while it is a song that resonates with Christian nationalists in the South today, McWhirter points out that it was protested in the South because “it ‘teaches wrong history.’”

On the other hand, Black communities didn’t resonate with songs about commands, thrones, conquests and casting down rebellions. Instead, they resonated with songs about liberation.

In The Spirituals and the Blues, James Cone points out: “In the spirituals, Black slaves combined the memory of their fathers with the Christian gospel and created a style of existence that participated in their liberation from earthly bondage. … The divine liberation of the oppressed from slavery is the central theological concept in the Black spirituals. … The message of liberation in the spirituals is based on the biblical contention that God’s righteousness is revealed in deliverance of the oppressed from the shackles of human bondage.”

Between spiritual freedom and earthly freedom

Because Black worshipers had to sing in code, many of their songs could have been taken as speaking more about the eternal freedom of heaven than about their earthly freedom. Cone says this was by design.

“White song collectors heard what the slave permitted them to hear.”

“Slaves lived in a society without any political, economic or personal security, and they had to camouflage their deepest feelings,” Cone explained. “White song collectors heard what the slave permitted them to hear. … The slave knew that a too-obvious reference of a condemnation of whites or a slight reference to political freedom in the presence of white people could mean his or her life.”

But as the possibility of liberation became more real, the political boldness of the lyrics became more clear.

“My contention that the pre-Civil War songs (although ambiguous) did in fact refer to earthly freedom is supported by the fact that Black people made unequivocal statements as soon as the need for equivocation was removed,” Cone wrote. “These are the songs that Blacks sang in response to the Civil War and emancipation.”

One common thought many white Christians have today is that song lyrics about defeating the enemies is referring to a “spiritual freedom” rather than to a political freedom. But from the perspectives of those who are oppressed by white Christians, Cone says, “This is not a ‘spiritual’ freedom; it is an eschatological freedom grounded in the events of the historical present … . Freedom, for Black slaves, was not a theological idea about being delivered from the oppression of sin. It was a historical reality that had transcendent implications.”

Between the dehumanizing and the human

Black worshipers understood that spiritual expression came from what it meant to be human. So when their white overseers controlled their expression of spirituality, they were dehumanizing them.

Cone writes: “To be enslaved is to be declared nobody, and the form of existence contradicts God’s creation of people to be God’s children. Because Black people believed they were God’s children, they were affirmed in their somebodiness, refusing to reconcile their servitude with divine revelation. They rejected white distortions of the gospel, which emphasized the obedience of slaves to their masters. They contended that God willed their freedom and not their slavery.”

One subtle, coded way Black communities affirmed their humanity was through the simple pronoun “I.”

Eileen Guenther explains: “‘I’ appears frequently in the spirituals but does not solely refer to the singer. Rather, it declares that the slave is, in fact, a person in a society that denied that recognition, designating the slave as nothing more than property. The ‘I’ is a ‘communitarian word, the expression of collective consciousness.’”

But while histories of slavery rightly emphasize how white people dehumanized Black people, Cone reminds us that our history is even more about how Black people sang their way through white assault in order to be liberated through the affirmation of their humanity.

“Black history is also the record of Black people’s resistance, an account of their perceptions of their existence in an oppressive society.”

“If Black history were no more than the story of what whites did to Blacks, there would have been no spirituals,” he notes. “Black history is also the record of Black people’s resistance, an account of their perceptions of their existence in an oppressive society. What whites did to Blacks is secondary. The primary reality is what Blacks did to whites in order to delimit the white assault on their humanity.”

Between then and now

In the decades after the Civil War, as new forms of oppression began to form, the songs of power and liberation within white and Black communities began to fade.

“As veterans, civilians, immigrants and their children turned to other matters, few needed to be reminded of why they slaughtered each other in the 1860s,” McWhirter explains. “Thus, not only did slave spirituals decline after the war, so too did the political songs that had so dominated the war years. Even pieces that were still performed had been partially neutered.”

“As veterans, civilians, immigrants and their children turned to other matters, few needed to be reminded of why they slaughtered each other in the 1860s,” McWhirter explains. “Thus, not only did slave spirituals decline after the war, so too did the political songs that had so dominated the war years. Even pieces that were still performed had been partially neutered.”

Yet with the rise of Christian nationalism and the rampant embrace of retributive justice in white evangelicalism today, political power songs are becoming popular once again in white communities. And with white worship leaders increasingly embracing white Christian nationalist politics, it’s important that we learn from the political worship songs of our past and be honest about how lyrics shape our posture toward ourselves and others.

Then as we look for new spaces to meet in a culture that is so racially and politically divided and as we write new songs to express our spirituality, perhaps we should begin by listening to the Black communities of songwriters who sang prostrate, under wash bins, and with clarity and code that emphasized liberation through freedom and an embrace of our whole common humanity.

Rick Pidcock

Rick Pidcock is a 2004 graduate of Bob Jones University, with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Bible. He’s a freelance writer based in South Carolina and a former Clemons Fellow with BNG. He recently completed a Master of Arts degree in worship from Northern Seminary. He is a stay-at-home father of five children and produces music under the artist name Provoke Wonder. Follow his blog at www.rickpidcock.com.

Related article:

Is there a balm in singing the spirituals, and if so, who should sing them? | Analysis by Rick Pidcock

Baylor’s Black Gospel Archive and Listening Center now open to the public