Charlotte’s westward expansion — beyond Uptown, Biddleville, Wesley Heights — was in full swing around 1924, when Julia Alexander and her family decided to subdivide and sell off her deceased father’s estate, called Enderly. The old farm would become the site of hundreds of houses, plus neighborhood businesses.

And as it is with Baptist people, anywhere there was a new neighborhood, there was a new Baptist church. By December 1925, the Glenwood Baptist meeting had official status with the Mecklenburg Baptist Association. The 41 charter members met in various spots along Tuckaseegee Road, but as the church grew over the rest of the Roaring ’20s, it became clear they needed a building of their own.

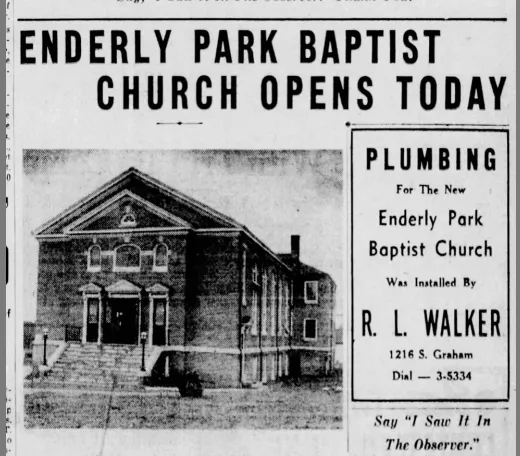

In 1930, in the full throes of the Great Depression, the trajectory of the church — by then called Enderly Park Baptist — was clearly on the way up, and so preparations for a new structure were made. In April of that year, the membership met as part of a revival series and voted to begin constructing a new building.

In 1930, in the full throes of the Great Depression, the trajectory of the church — by then called Enderly Park Baptist — was clearly on the way up, and so preparations for a new structure were made. In April of that year, the membership met as part of a revival series and voted to begin constructing a new building.

Julia Alexander donated land at the corner of Tuckaseegee and Enderly Road to site the structure. At the revival meeting the night of the decision, Rev. J.M. Page preached on the Gerasene Demoniac, from Mark 5. His message was titled “Getting Rid of Jesus.”

The building was eight years from its conception to its completion and dedication, doubtless slowed by the ongoing Depression. At completion, it was a fine structure, with 18 classrooms plus a meeting space that would hold 500 for morning worship until a larger sanctuary could be built. That separate project would take 25 years to see to completion.

Most notably, the building had a new technology in it: air conditioning. Nothing along Tuckaseegee Road has ever been described as “stately,” but it is easy to see how people would take pride in this facility they had worked to fund and construct for nearly a decade.

Most notably, the building had a new technology in it: air conditioning. Nothing along Tuckaseegee Road has ever been described as “stately,” but it is easy to see how people would take pride in this facility they had worked to fund and construct for nearly a decade.

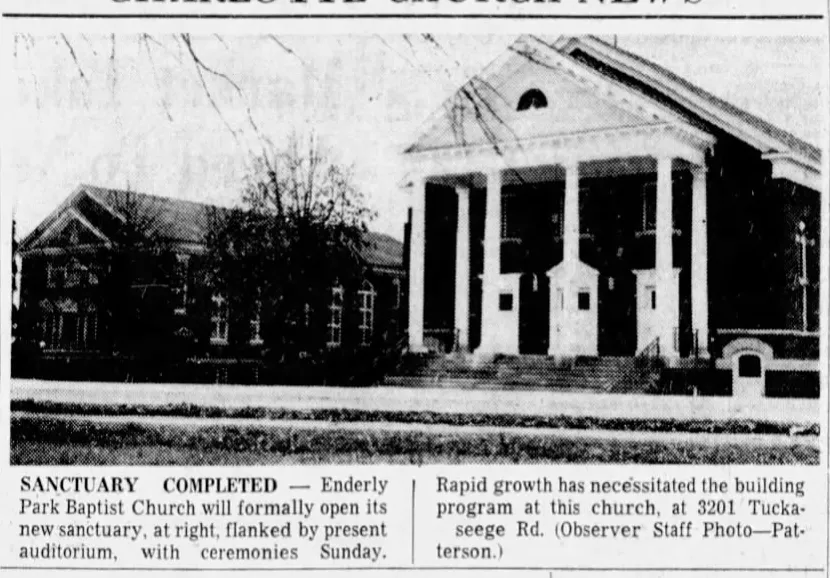

By 1950, there were more than 1,000 members on the roll. It was time to build the new sanctuary, and there was money available to do it. The 1950s were a time of enormous growth for Southern Baptist churches like Enderly Park. The Southern Baptist Convention had a fully staffed architecture division at the time, whose jobs were to assist churches with every phase of building campaigns.

You can feel the similarity to other SBC churches of the time when you walk in.

Enderly Park Baptist Church sited the new sanctuary in a way that would help make its importance clear. The sanctuary steps nearly touch the sidewalk. It is one of only a handful of buildings along Tuckaseegee, and by far the largest one, that approaches the street with little or no setback. Nearly every other business or house in the neighborhood sits 15 feet or more back from the sidewalk.

The structure was completed in 1954, to the great joy of its members.

The structure was completed in 1954, to the great joy of its members.

But the sanctuary would be short-lived, as sanctuaries go, for Enderly Park Baptist. By the mid-1970s, the neighborhood was in the midst of white flight. Its nearly 100% white population was moving further out of town to new suburban developments, and Black residents looking for homes after being displaced by Charlotte’s half-dozen urban renewal projects were moving to West Charlotte neighborhoods in large numbers.

Enderly Park Baptist Church joined white flight and began meeting seven miles away at Northside Baptist, separate from the already existing congregation there. They renamed themselves University Hills Baptist and by 1977 were breaking ground on a new facility less than one mile from the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, nearly 12 miles from their original home.

The story of their relocation, as some University Hills members once told me, was that the church had discerned a new sense of call to student ministry, and so they relocated to the university area. I don’t doubt that’s what some people told themselves and one another, but surely the story was more complex.

“Jesus calls the loudest and most clearly when there are advantageous real estate opportunities available.”

However, regular readers of my writing will note my interest in how Jesus calls the loudest and most clearly when there are advantageous real estate opportunities available. That Jesus really keeps his nail-scarred fingers on the pulse of the housing market.

When I moved to Enderly Park in 2005, one of the first Sunday mornings I walked one block over to go to church at Mt. Carmel Baptist, in the former Enderly Park Baptist building. Mt. Carmel had purchased the facility from its former inhabitants in 1977.

Mt. Carmel is a historic congregation, started in the Biddleville neighborhood adjacent to Johnson C. Smith University. Their long-time pastor, Casey Kimbrough, was so very kind to me in our first few weeks in the neighborhood, generous with his time, incisive with his words. He helped me see some of what I’ve spent the past two decades learning. But that first Sunday we visited, we learned they were spending the week packing up the offices and prepping their new building on a large campus five miles west. We wound up going to church elsewhere.

The next congregation in the building, after a period of vacancy, was Temple Church International. Temple had a complex relationship with the neighborhood. There were neighbors who were faithful attendees and deacons who were very poor, living in substandard housing, but fiercely committed to the congregation. When our beloved Khalil was killed at only 13 years old, they carried his casket out of the church and into a horse-drawn carriage that carried him down Tuckaseegee Road a way.

But the clergy didn’t think of living here. They and the staff had flashy cars and travel budgets. There were promises of neighborhood ministry that never worked out because the building was in bad shape. Money issues eventually caught up to them, and for the past five years the building has sat mostly vacant.

But not fully vacant. Charlotte, like many cities, is in a long-term housing crisis. Thousands of residents here are desperate, and desperate people do things like squat in abandoned buildings. When a city full of the rich people — and rich Christians — builds a system that requires some people’s desperation in order to maintain others’ hoarding, well, folks do what they have to do.

One dear friend of ours, who grew up here in the neighborhood, occasionally was part of the encampment in the church building. He described a complex scene. There was solidarity among those who had no other options, the kind of secret economy of mutual care rarely glimpsed from the outside. There also were opportunistic people who took advantage of desperate ones. It was both a safe haven and a briar patch of danger. It was entirely unsuitable for human habitation, and at the same time necessary because of the determined hoarding of folks across town.

But now, those campers have all been run off, part of a long-term campaign to run poor people out of Enderly Park altogether. The photo at the top of this column shows what the building looked like earlier this week

Here’s the parsonage coming down on Tuesday.

Here’s the parsonage coming down on Tuesday.

Here is a short video from Thursday morning:

It is Advent, and around the world Christians are asking about whether there is “room in the inn.” You have to admit, it’s a clever strategy: If you tear down the inns, you never have to admit that your answer is “no.”

Now you might wonder, What’s next? Would you believe me if I told you luxury townhomes?

“We find the presence of the Christ in the world in places of suffering and scorn and oppression.”

Among my clearest religious convictions is that we find the presence of the Christ in the world in places of suffering and scorn and oppression. That’s not exactly an original thought. It’s the nature of the story, and the testimony of the faithful down through the years, so far as I can see it. The God made known in Jesus Christ exhibits a “preferential option for the poor,” as the Liberation theologians say, and as Mary sings in the Magnificat.

Which leads me back to the beginnings of the building, and the preacher who was preaching when they were planning its construction. Now a real estate developer, aided and abetted by bankers and financiers and opportunity funds and by the City of Charlotte and by the State of North Carolina, have run the poor out of one more place. It’s just like that preacher 90-plus years ago was preaching, and at the same site: They’re getting rid of Jesus.

Greg Jarrell is co-founder and Chief Door Answerer at QC Family Tree, a community of rooted discipleship in the West Charlotte, N.C., neighborhood of Enderly Park. Greg shares life there with a host of neighbors who have become family, as well as his wife, Helms, and sons, John Tyson and Zeb. He is the author of A Riff of Love: Notes on Community and Belonging.

Greg Jarrell is co-founder and Chief Door Answerer at QC Family Tree, a community of rooted discipleship in the West Charlotte, N.C., neighborhood of Enderly Park. Greg shares life there with a host of neighbors who have become family, as well as his wife, Helms, and sons, John Tyson and Zeb. He is the author of A Riff of Love: Notes on Community and Belonging.

Related articles:

In our neighborhood, ‘eyes on the street’ takes on deeper meaning | Opinion by Greg Jarrell

The folly of naming a place you don’t understand | Opinion by Greg Jarrell