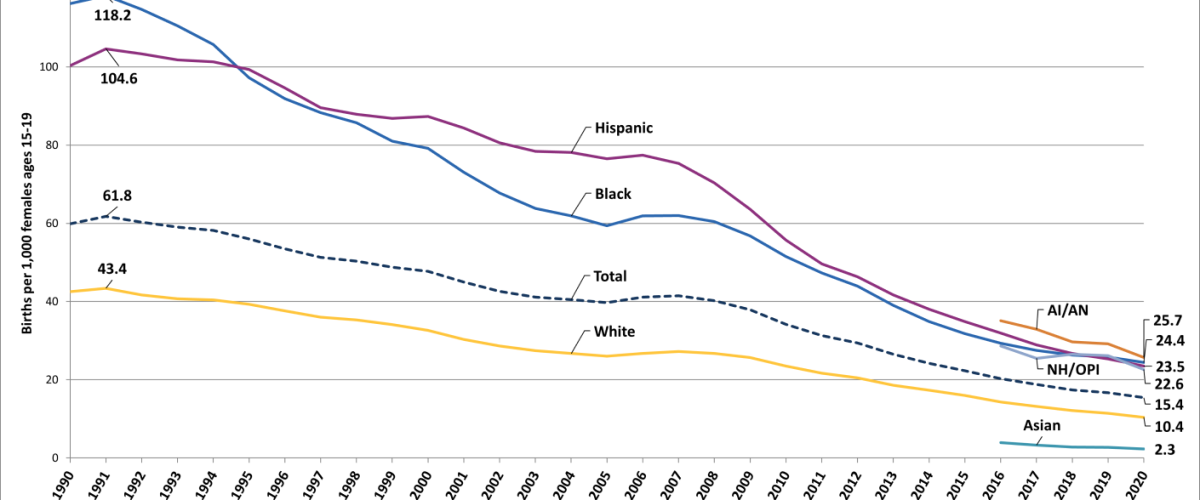

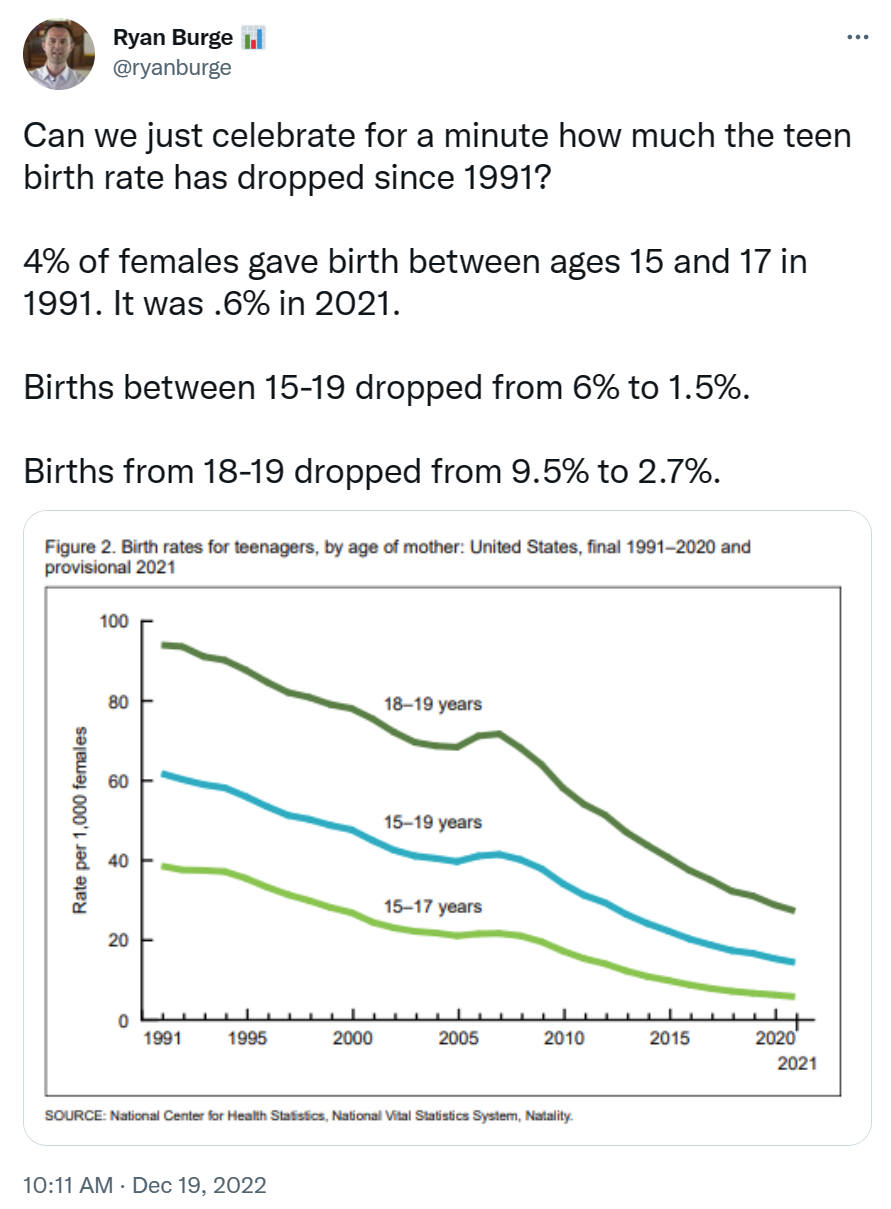

Ryan Burge — pastor, author and statistician — frequently shares intriguing research data on his Twitter account. On Nov. 19, Burge tweeted a graph showing the dramatic decrease in the amount of recorded U.S. teen pregnancies with the caption, “Can we just celebrate for a minute how much the teen birth rate has dropped since 1991?”

The data show a 75% reduction in the teen birth rate since 1991.

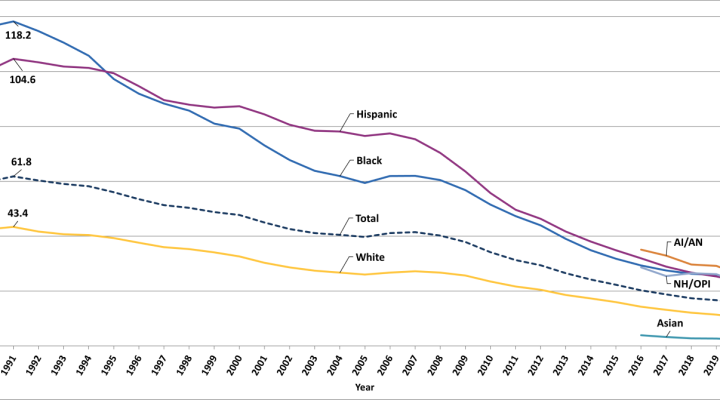

Measured in 1991, the rate was roughly 61.8 births per every 1,000 females ages 15 to 19. In 2020, it was 15.4. Burge’s graph, using data from the National Center for Health Statistics, breaks down the age demographics into more specific frames, showing a dramatic and consistent decrease in the number of both younger (ages 15-17) and older (ages 18-19) girls who give birth yearly.

Measured in 1991, the rate was roughly 61.8 births per every 1,000 females ages 15 to 19. In 2020, it was 15.4. Burge’s graph, using data from the National Center for Health Statistics, breaks down the age demographics into more specific frames, showing a dramatic and consistent decrease in the number of both younger (ages 15-17) and older (ages 18-19) girls who give birth yearly.

This is certainly a milestone to be celebrated.

But why?

There are multiple factors to consider when interpreting this data. Twitter users responded to Burge and made estimates about the causes of this decrease, suggesting things like access to abortion services, access to contraceptives as well as a general decrease in the number of teens having sex must be correlated.

These suggestions make sense.

If teens have the option to terminate a pregnancy, that will reduce the rate of teen births. This first suggestion, however, does not exactly fit what we know about teenage abortions. Although pregnant teens tend to have abortions more often compared to adult women, the overall number of teens receiving abortive services has decreased over the years. Additionally, teens may find it difficult to receive abortive services as a minor, since laws in some states may prohibit teens from making that choice without parental consent, or from making that choice at all.

The other two suggestions line up a bit better.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 90% of teens polled in 2013 said they used some form of birth control. The two most common forms were condoms and “the pill.” And while these are not the most effective forms of birth control in comparison to Long-Acting Reversible Contraception methods (IUDs and implants), it is still likely a factor in why teens who have access to them and choose to have sex are getting pregnant less often.

Last, and most surprisingly, teens are having less sex than they used to. According to the Institute for Family Studies, less than 40% of American high schoolers have ever had sex. In fact, teens are engaging in less and less risky behavior across the board, with decreases in smoking and instances of drunk driving.

So, Twitter users had some good, educated guesses about causation for Burge’s statistics. There are also other factors to consider related to this research.

Factors known to affect teen pregnancy

According to the Office of Population Affairs under the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, there are individual, familial and community-based factors that impact a teen’s likelihood of becoming pregnant.

Teens are less likely to get pregnant if they:

- Feel connected to and do well in their school environment

- Feel connected to and supported by their families

- Lived with both biological parents at age 14

- Have mentors and/or a strong connection to their community

- Have access to family planning services and information (such as gynecological care or comprehensive sex education)

- Have a positive attitude surrounding contraception methods

Teens are more likely to get pregnant if they:

- Have a mother who gave birth as a teen

- Have a mother with lower levels of education

- Live in a community with high rates of substance abuse, violence and hunger

- Do not have access to family planning services and information

- Have a negative attitude surrounding contraception methods

- Have a history of mistreatment by doctors or a general distrust of doctors

In addition to these factors, when compared by race, white and Asian teens are the least likely to experience teen pregnancy, while American Indian/Alaskan Native and Black teens are the most likely.

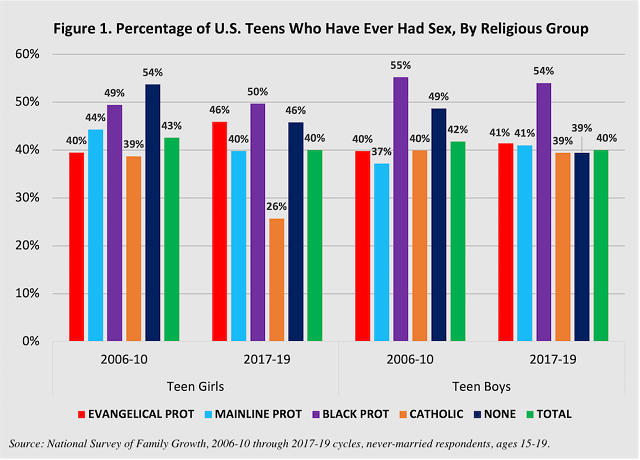

Although there was an overall decline in sexual intercourse among all teenagers, the rate of decline was less among religious teenagers.

Religious teens

Despite all this, there is a slight (and intriguing) difference in the rates at which religious teens have premarital sex. According to another set of data published by the Institute of Family Studies, researchers found although there was an overall decline in sexual intercourse among all teenagers, the rate of decline was less among religious teenagers.

For teenage girls who identified as mainline Protestant, evangelical or Black Protestant there was no significant decline. For Catholic teen girls there was a 39% decline from 2006 to 2010 and a 26% decline from 2017 to 2019. For non-religious teen girls, the decline rates in those same periods were significantly higher: 54% and 46%.

Among teen boys, there was only a clear and significant decline in sexual activity among non-religious boys, and among the various religious groups, researchers found “the declines were too small to be significant.”

Among teen boys, there was only a clear and significant decline in sexual activity among non-religious boys, and among the various religious groups, researchers found “the declines were too small to be significant.”

The general decline in teen sexual activity may be explained by factors such as a fear of “rough” sex depicted in media, increased usage of online porn and rising concerns about the logistics or consequences of sex (such as consent rules, the risk of STI transmission or pregnancy scares). But these reasons do not explain the difference among religious teens.

However, there may be multiple factors relating to purity culture that do.

First, religious teens may be less likely to have received comprehensive sexual education, and thus do not know all the risks involved with the choice to have sex. Additionally, a negative attitude Christians may have toward birth control methods may discourage their use, increasing pregnancy rates.

Some research on purity culture has found religious teens sometimes choose not to have things like condoms or birth control available to them (even if they know they may want to have sex) because having those things in their possession prior to sex makes them feel as though they are “planning” out the sinful act of premarital sex.

Second, religious teens who attend a church that participates in purity culture, although their theologies promote abstinence, may still exist in a social environment that facilitates unhealthy sexual behavior (and possibly sexual violence). This is because the purity movement does not adequately teach about consent as a factor in having sex, but instead focuses on temptation and lust. And inadequate teachings related to sexual purity can create hypersexualized or scandalized attitudes toward a person’s own body, or the bodies of others, that lead to sexual behavior.

Third, according to Pew Research Center, half of U.S. Christians think causal sex (if it is between consenting adults) is “sometimes or always acceptable.” This positive attitude toward sex, mixed with negative attitudes toward birth control, might be a factor in why some Christian teens are not lowering their frequency of sexual encounters (and may be at a higher risk of pregnancy than other groups).

Human trafficking

Another set of issues related to purity culture that may be important to consider in the context of Burge’s data is sex trafficking and human trafficking.

Coupled with the rise of the evangelical purity movement, which was jumpstarted by the Southern Baptist Convention with True Love Waits in the 1990s, American Christians began considering sex trafficking and human trafficking as pressing issues. Of course, sex trafficking and human trafficking should be considered serious issues across all people groups, both religious and secular, as it is a devastating and life-altering practice.

But for evangelicals practicing purity culture, sex and human trafficking have an increasingly deeper importance, as the prospects of someone being forced to engage in premarital or extramarital sex, or to have a pregnancy forcibly aborted, are fundamentally opposed to popular evangelical values surrounding sexual purity. Thus, Christian advocacy and involvement in the issues of sex and human trafficking have increased over the years since the modern purity movement began, making it one of a few crises the church is known for passionately, and some may say obsessively, speaking out against.

But for evangelicals practicing purity culture, sex and human trafficking have an increasingly deeper importance, as the prospects of someone being forced to engage in premarital or extramarital sex, or to have a pregnancy forcibly aborted, are fundamentally opposed to popular evangelical values surrounding sexual purity. Thus, Christian advocacy and involvement in the issues of sex and human trafficking have increased over the years since the modern purity movement began, making it one of a few crises the church is known for passionately, and some may say obsessively, speaking out against.

But often the terms “sex trafficking” and “human trafficking” seem like phenomena that occur in other places. We often imagine modern slave trade occurring in places like third-world countries, and not in our own states, counties or cities.

However, sex trafficking and human trafficking are huge problems globally. For example, according to the World Population Review, 199,000 incidents of human trafficking occur in the U.S. each year, and on a global scale, the U.S. is ranked one of the worst countries in terms of human trafficking risk.

This is a crisis occurring right in front of us. Even on social media, as shown by the recent arrest of brothers Andrew and Tristan Tate.

Andrew Tate is a former kickboxer and controversial online influencer, known for his demeaning, misogynistic and sexually objectifying comments about women. Tate moved to Romania in 2017, where he, his brother and two other suspects allegedly organized a crime group that facilitated the forceful recruitment, housing and sexual exploitation of women. Women were lured by the men after they lied about seeking romantic relationships with them and were subsequently forced to create pornographic content to be sold online. If the women refused, they were threatened with violence.

Police allegedly had been searching for Tate and the group but did not know his location until he posted a video about environmental activist Greta Thunberg, which included a pizza box from a local restaurant that was used to locate and arrest them.

Are the data accurate?

Crimes like this, and the issue of sex trafficking altogether, introduce the question of whether data depicting the number of teenage pregnancies and births are accurate.

In 2020, the National Human Trafficking Hotline Data Report found 28% of the victims they identified in sex trafficking situations were minors. Further, according to the 2009 National Report on Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking, data suggest that in the U.S., there are anywhere from 100,000 to 300,000 American children victimized by child prostitution each year. However, the report also states there is an overall inability for researchers to “obtain a true count of the numbers of victims of child sex trafficking” due to multiple factors such as lack of awareness and differing tracking protocols across states.

According to the report, trafficking as a crime has a broad definition, “including proof of recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, obtaining or maintaining a person for sexual exploitation.” The trafficked individual does not necessarily have to be transported by the trafficker; trafficking can be proved by any of these elements independently, so long as the sexual use of the victim was commercial (the reception of money or something of value separates the crime from other types of sexual abuse or assault).

So, children can be trafficked in a variety of ways. This broad definition means trafficking does not always look the same and can be difficult to identify or easy for a trafficker to hide.

What does this have to do with teen pregnancy?

In 2015, Freedom Network USA published a statement on Human Trafficking and Reproductive Rights. This statement addressed the control traffickers have over the bodies and reproductive rights of their victims, putting them at risk of various dangerous physical and psychological conditions. The statement included survivor stories, exemplifying “the need for reproductive health care for survivors of trafficking.”

Victims mentioned that, while being commercially sexually exploited, they were forced to have abortions in the event they became pregnant.

In multiple stories, victims mentioned that, while being commercially sexually exploited, they were forced to have abortions in the event they became pregnant. In all these cases, victims did not have access to proper medical care, and this led to a great deal of pain and suffering during their captivity (atop the violence already being subjected upon them), as well as long-term medical consequences such as infertility or the need to take medications to mitigate painful symptoms.

Aside from (sometimes instead of) forced abortions, some babies are born into situations of sex and human trafficking. While most victims enter trafficking situations between the ages of 9 and 17, there is a spike in the number of victims aged birth to 8, according to the Counter Trafficking Data Collaborative. This spike, researchers say, is due to “the number of children who are born into trafficking.” For reference, 26% of trafficked children enter situations of trafficking between ages birth to 8, compared to 33% who enter between 15 and 17.

So, if a newborn enters a trafficking situation, they are either sold by or stolen from a mother who is not being trafficked or born to a mother who already is being trafficked.

But as the National Report on Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking addresses, it is not known exactly how many teenage girls are victims of sex trafficking each year, nor do we know exactly how many of these teen girls experience pregnancy, miscarriage, forced abortions or childbirth each year.

Is the rate of teen pregnancy for trafficked teen girls also decreasing, as Burge’s encouraging data finds for teen girls overall? The currently available data does not answer this question.

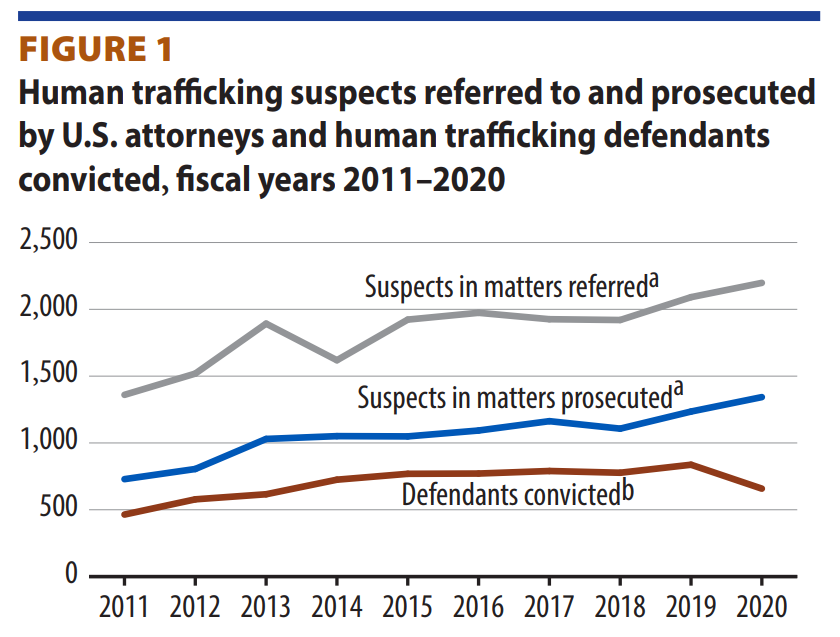

What is known is that between 2011 and 2020, the number of persons prosecuted for human trafficking increased by 84%. So, it seems more traffickers are being caught and punished for their crimes than before, which is a good thing.

Something to celebrate and something to worry about

And it is also a good thing to celebrate the measurable reduction of teen pregnancy rates. This is a triumph. More teens are choosing to wait to have sex, and the ones who are having sex tend to do so responsibly. This creates safer and more secure situations for these teens as they make the transition into adulthood without the added stress of pregnancy and child-rearing.

As for sex trafficking, although we do not know exactly how prevalent the issue of teen pregnancy is or is becoming for victims, it is important to continue lobbying for more action that protects children and adults who experience this type of violence.

Just as access to individual and community support, as well as reproductive health care or family planning services helps teens overall reduce their likelihood of becoming pregnant, these things also can positively impact the lives of those in violent or dangerous situations.

Mallory Challis is a senior at Wingate University and serves as BNG’s Clemons Fellow.

Related articles:

Can Christians come together to reduce the need for abortion? | Opinion by Susan Shaw