I recently highlighted the Jesus-Joshua problem: Jesus wants us to love our enemies. Joshua wants us to slaughter them. Both can’t be right. But what about the demand for justice that reverberates throughout Scripture, from Genesis to Revelation? If we love the oppressor; doesn’t that worsen the plight of the oppressed?

From start to finish, the biblical narrative revolves around the existential threat posed by evil people — the oppressor, the enemy, the person of violence, the unrighteous and the sinner. The terminology varies, but the reality is constant. Oppressors wound, slaughter, burn, destroy, torture, enslave and plunder. Oppressors leave famine, plague and mass starvation in their wake. In the Bible, the oppressor always is pounding on the door, about to break in and do his worst.

Alan Bean

The biblical concept of “being saved,” has little to do with ransomed souls drifting up to heaven; in virtually every case, we are saved from oppressive people. Biblically speaking, justice is what happens when God thwarts human evil. The nature of the threat varies. It might be an individual, an invading army or an outbreak of plague and pestilence. But human strength and ingenuity are insufficient. Salvation comes from God alone.

In the biblical story, God saves the oppressed from the oppressor. “Deliver me from my enemies, O my God,” the Psalmist cries. “Deliver me from those who work evil; from the bloodthirsty, save me!” (Psalm 59: 1,2).

Oppressors abound

Even in times of peace and prosperity, oppressors abound. Wealthy landlords reduce the poor of the land to virtual slavery. The powerful steal ancestral lands, and the courts do nothing because the legal system has been bought off. “Woe to those who make iniquitous decrees, who write oppressive statues,” Isaiah cries, “to turn aside the needy from justice and to rob the poor of my people of their right, to make widows their spoil and to plunder orphans!” (Isaiah 10:1,2)

If we find ourselves longing for a more “spiritual” narrative, it’s because our lives aren’t teetering on the brink of disaster.

If we find ourselves longing for a more “spiritual” narrative, it’s because our lives aren’t teetering on the brink of disaster.

The biblical plot is complicated by God’s reluctance to play the savior role. The oppressor smashes down the door, innocent blood is shed, free people are enslaved or driven into exile, women are raped, children are orphaned, God’s holy temple is ground to dust, and God does nothing to make it stop.

Sometimes God comes through in the nick of time. God parts the Red Sea and blinds a Syrian army, but often God provides no deliverance at all. In fact, the Bible was written, in large part, to justify God’s unwillingness to crush the oppressor.

A mosaic discovered in an ancient synagogue in Israel depicting the parting of the Red Sea. (Photo/Baylor)

Human sinfulness receives much of the blame. We fall prostrate before false gods, we allow the wealthy to despoil the poor, we afflict the orphan and the widow, and then we beg God to intervene on our behalf? That’s not going to happen! Yet if we but turn from our low-down ways, the salvation of God will come speedily.

Dream wouldn’t die

By the time Jesus enters the picture, the children of Abraham had been living under the heel of foreign oppression more than 800 years. If God’s people hadn’t reformed in that stretch of time, it seemed unlikely salvation was waiting in the wings. Resistance seemed futile. Rome was a superpower with highly disciplined armies circling the Mediterranean. But the salvation dream wouldn’t die. At any moment, it was popularly asserted, God’s long-promised Messiah would appear from heaven to lead the oppressed to victory.

In such an environment, talk of forgiving, loving and praying for the Romans and their Jewish collaborators sounded like madness. But that is what Jesus preached.

The people who followed Jesus around the Galilean countryside were poor, sick, hungry, dispossessed and desperate.

But although Jesus told his followers to greet the Roman oppressor with acts of compassion, “the least of these” were his brothers and sisters, and their well-being was his primary concern. Jesus felt a particular love for children and urged his followers to protect them at all costs. Those who failed to care for the poorest and most vulnerable of God’s children earned his unremitting scorn. In his first public sermon, Jesus quoted the words of Isaiah the prophet: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me because he has anointed me, to preach good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives.”

Most biblical references to hell are found on the lips of Jesus and invariably are directed at those who oppress the poor and the desperate.

Most biblical references to hell are found on the lips of Jesus and invariably are directed at those who oppress the poor and the desperate. This raises an obvious question: If Jesus was so eager to send oppressors to hell, why do they merit our forgiveness and compassion?

This odd mix of compassion and judgment particularly is evident in the parable of the sheep and the goats found in Matthew 25. The parable ends with the righteous sheep inheriting God’s kingdom while the sinful goats “go away into eternal punishment.”

Loving Matthew 25

Liberal Christians love Matthew 25 because it prioritizes compassion over right belief. Conservative Christians quote the passage because Jesus affirms the reality of hell. But there’s a problem. If only those who show compassion for the hungry, the thirsty, the prisoner, the immigrant and the prisoner make the final cut, who can be saved?

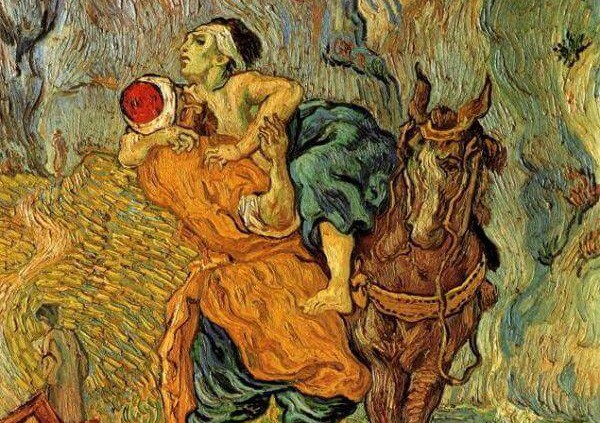

Be honest, now. Do you show compassion for “the least of these,” or, like the religious leaders in the good Samaritan story, do you frequently pass by on the other side?

“The Good Samaritan,” Vincent van Gogh

If you’re like me, you have moved to a neighborhood where you are effectively shielded from human despair. At least, that’s the plan. We occasionally send off a few dollars for disaster relief, and we toss a few coins into the Salvation Army bucket at Christmas — at least we did before we started shopping online. But if you do more than that, it’s probably because you belong to a church or a civic organization that engages in acts of corporate kindness. Compassion always has been a team sport.

We don’t want that Jesus hanging out in our neighborhoods, and if we spot him, our first impulse is to call 9-1-1.

We have gone to heroic lengths to ensure that we never cross paths with “Jesus in his distressing disguise,” to borrow a phrase from Mother Theresa. We don’t want that Jesus hanging out in our neighborhoods, and if we spot him, our first impulse is to call 9-1-1.

If the kingdom is reserved for people who extend compassion to all, with a laser focus on the least of these, we’re not going to fit in. We aren’t ready for the party.

Committed to the least of these

Does that mean Jesus is going to throw us into hell? That’s not what Matthew 25 is about. Jesus is desperately committed to the least of these. He inhabits their misery. He wants the hurting to stop. That’s why he calls for unqualified compassion.

Concrete acts of compassion don’t get us into the kingdom; acts of compassion are the kingdom. When we care for the Jesus who confronts us in the sick, the hungry and the homeless, the refugee and the incarcerated, our frozen hearts begin to thaw. Compassion requires sacrifice, especially if we head upstream and grapple with the tangled roots of human despair. You have probably heard compassion means “to suffer with.” That’s true. But that suffering ushers in kingdom joy.

The reverse also is true. Indifference makes us miserable. Encased within our fear of suffering, insensitive to the pain around us, we grow blind to our deepest needs. Insulated from a hurting world, we begin to freeze up emotionally. Our lives become increasingly cramped, stifled, suffocating and alienated. We subsist in a hell of our own making, and we don’t even know it.

Jesus saves us from hell by calling us to lives of compassion. The parable of the sheep and goats is about discipleship. It’s about moral transformation. It’s about taking on the mind of Christ. It’s about exchanging the hell of indifference for the kingdom joy of compassion.

Alan Bean is executive director of Friends of Justice, an alliance of community members that advocates for criminal justice reform. He lives in Arlington, Texas.

Related articles:

A midnight train to nowhere: How Journey’s signature song anticipated the rise of MAGA

The gospel of universal compassion

The white church isn’t dying; it’s in exile

Remembering the struggle to integrate even ‘progressive’ churches in the 1960s