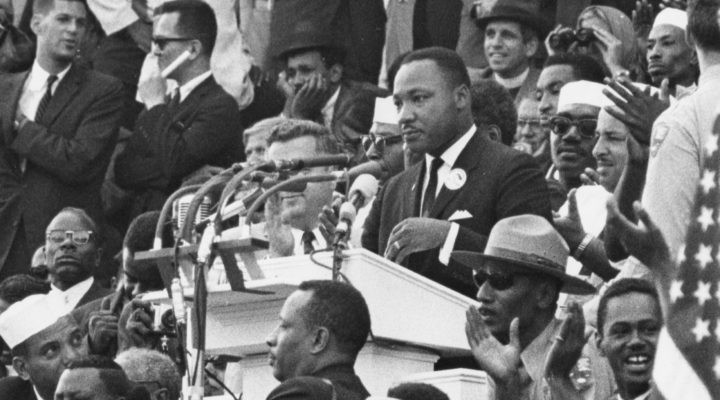

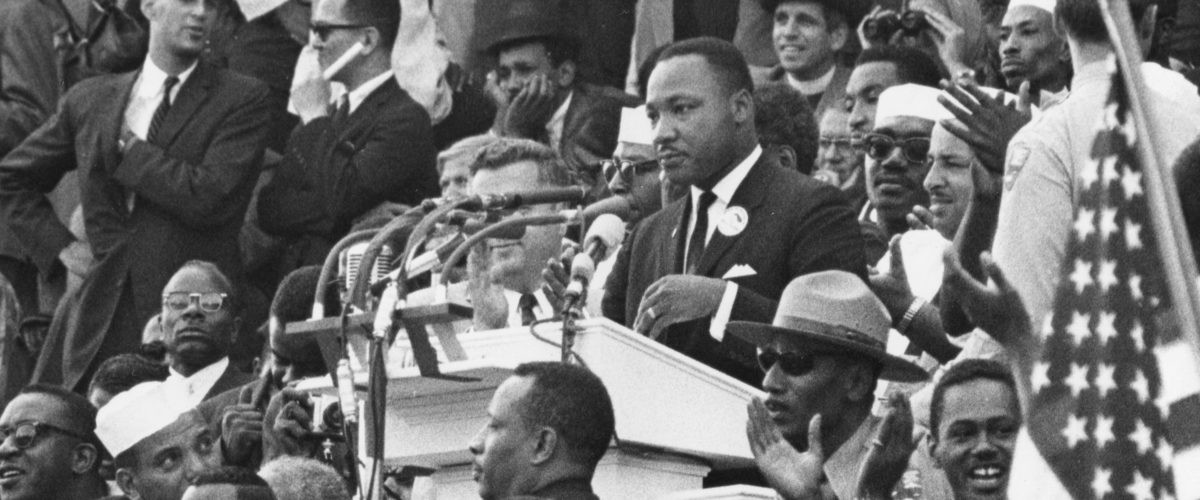

Martin Luther King’s role as a Civil Rights leader was heavily influenced by the Baptist tradition that gave structure to his ministry and activism, Jeremiah Chester said during a webinar presented by Baptist History and Heritage Society.

“We can’t separate his pastoral style and his pastoral conviction from his Baptist context. His autonomy, and that of the Baptist church which is free from a bishop’s authority and free from denominational oversight, allowed him to be guided by these convictions that are being ever clarified throughout his life,” said Chester, pastor of St. Mark Baptist Church in Huntsville, Ala.

Jeremiah Chester

Chester spoke in response to historian Paul Harvey’s summary of his 2021 book Martin Luther King: A Religious Life in the latest episode of the history society’s “Making Baptist History Public History” webinar series.

The book captures the evolution of King’s social justice strategies from his late teens until his assassination in 1968 and the steady spiritual and emotional grounding he received from his religious development.

King served as pastor of Dexter Avenue King Baptist Church in Montgomery, Ala., when he began his Civil Rights activism.

“You remind us that Baptist life is really about progression and not conservation. It’s about unlearning and relearning, not about regurgitation,” Chester said to Harvey. “This is what Baptists originally fought for: the ability to be free to hear and to follow God’s word and spirit afresh, to be free from popes and bishops and monarchs. The autonomy of the congregation and the freedom of the pastor are key to Baptist churches and are portrayed as the hidden ingredients to this and to this entire movement.”

King grew to become a “Baptist social gospeler” and social Democrat for whom civil rights was not just about creating a colorblind society but undergoing the total economic and social change needed to achieve it, said Harvey, professor of history at the University of Colorado.

“He held firm to certain core radical convictions, but he also underwent a constant process of thinking over and through those convictions. He grew. He evolved over time and as he did, he came to a clearer and arguably darker vision of the insidiously deep-rooted nature of American racism and the moral and practical complexities of promoting human brotherhood within a system that deliberately and systematically thwarted achieving it.”

King’s understanding of evil grew more profound along the way, Harvey said.

“We think of King as a great optimist, but that optimism arose from a profound sense of human evil.”

“We think of King as a great optimist, but that optimism arose from a profound sense of human evil. King’s dream is often portrayed as being a positive forecast of the days of human brotherhood to come,” he said. “The prophetic rage that King expressed most pronouncedly in the last three years before his assassination — 1965 to 1968 in particular — came in part from his sense of the intensity of the struggle against human evil.”

Paul Harvey

The centrality of nonviolence in the Civil Rights movement also deepened for King, especially as he interacted with Malcom X, Stokely Carmichael and others who disagreed with that approach, he added. “His sense that nonviolence was not just the means, but was itself the message, grew more radical over time as he confronted challenges from other Black radicals.”

The evolution of King’s message also emanated in part from his ability to assimilate and translate complex concepts into inspiring language to motivate his followers.

“From his youngest writings, he described himself as a profound advocator of the social gospel … and he morphed that into social democracy — that is to say a state that consciously works toward greater equality, toward the elimination of poverty and injustice, toward the equitable distribution of wealth, toward protecting jobs and livelihoods. Those were central to King’s dream.”

Harvey added that the development of King’s philosophy remained rooted in his religious formation. “He derived that from the Black gospel tradition to which he had been trained, and from his everyday observations from his boyhood forward about how inequality actually worked.”

And King was all too familiar with the overt forms of racism and replacement theory that are active in the U.S. today. He was prophetic about “the automation of jobs, police brutality, inegalitarian tax systems, systematic discrimination in housing and employment and the growing alliance of white supremacist forces with national conservatives interested in defending states’ rights and Western civilization.”

And King was all too familiar with the overt forms of racism and replacement theory that are active in the U.S. today. He was prophetic about “the automation of jobs, police brutality, inegalitarian tax systems, systematic discrimination in housing and employment and the growing alliance of white supremacist forces with national conservatives interested in defending states’ rights and Western civilization.”

King also came to see the merger of religion and politics as an evil to be battled, Harvey said. “He preached against the ‘false God of nationalism’ that could be perverted to evil ends when it became an excuse for the exercise of power over others. … King was attuned to how fascism could, and sometimes did, arise in America. And he knew where the phrase ‘America first’ came from to begin with. And he knew that it was a phrase shot through with echoes of ideas about a kind of fascist, white supremacist state.”

But those facts have almost completely been lost in the decades since his assassination and replaced by platitudes, misconceptions and lies by those who have appropriated King’s message for causes he would never have endorsed, Harvey said.

“He remains, in my estimation, a misunderstood martyr, at least in the eyes of the general public.”

“He remains, in my estimation, a misunderstood martyr, at least in the eyes of the general public. And the fate of martyrs is to be made into saints, and the fate of saints is to be made into statues, mausoleum pieces and irrelevant national holidays.”

An example came earlier this year when Republicans turned to social media to quote a snippet from King’s “I Have A Dream” speech, namely that they hope their children would not be judged by the color of their skin.

“The tough edges were whittled down over time,” Harvey said. “His status as a martyr and a saint made him useful for causes that he spent his entire career in vain against. And so, we have now the parade of twisted tweets and fake quotations that are paraded through the social media on King Day as the real King recedes from consciousness.”

Related articles:

Knowing a church’s history on slavery can be a nudge toward redemption, historians say

Author explains the history of ‘Peace Be Still’ and its social influence

Scholar traces how Black churches became centers of political engagement