In the summer of 2019, I rode a bus high into the Swiss Alps, a terror ride straight out of Six Flags, to visit the most important site in American race relations that nobody knows about.

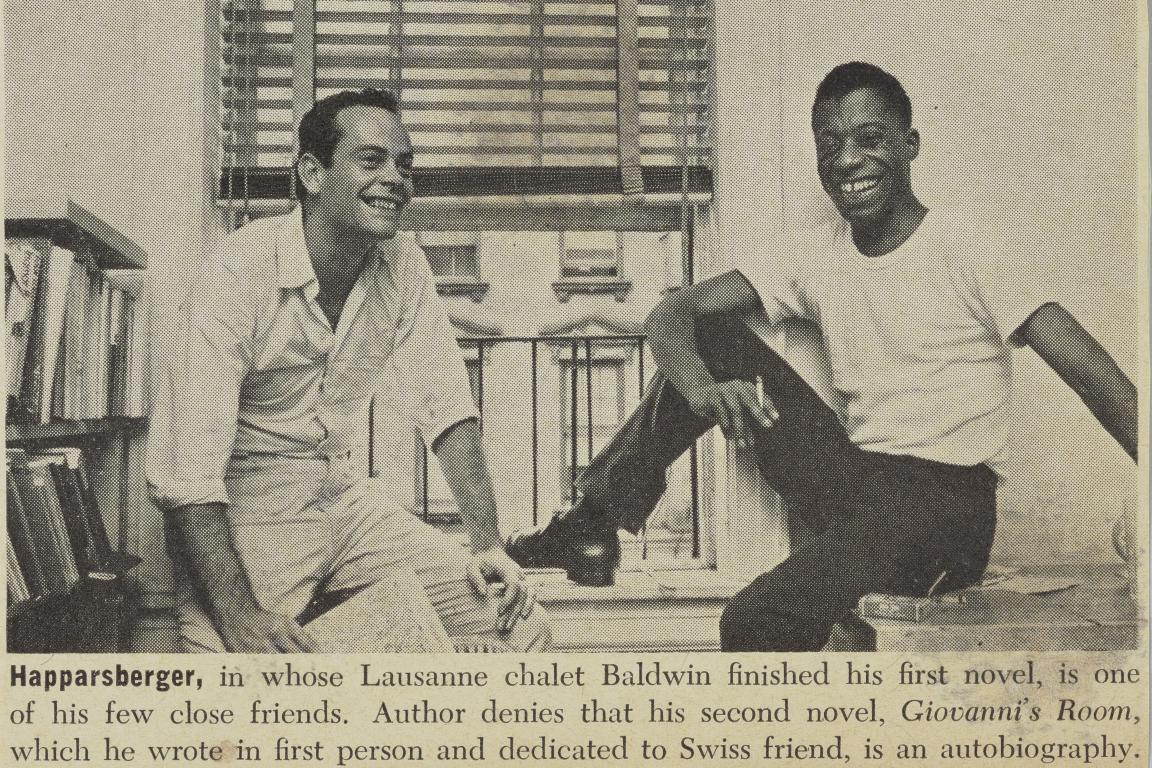

In 1951, the author and social critic James Baldwin came to the tiny village of Leukerbad to try and solve the problem of his first novel, Go Tell it on the Mountain, and what he experienced there in Switzerland not only changed his understanding of race and America, but speaks loudly to us in this very moment.

Leukerbad was (and to some extent remains) a tiny resort village whose year-round population is unrelievedly white. While Baldwin was there writing and thinking, the villagers thought of him as an exotic beast. They never had seen anyone like him before; in fact, their only awareness of people from Africa or of African descent came through the annual giving campaign through which the tiny local Catholic church “bought” Africans to convert them to Christianity.

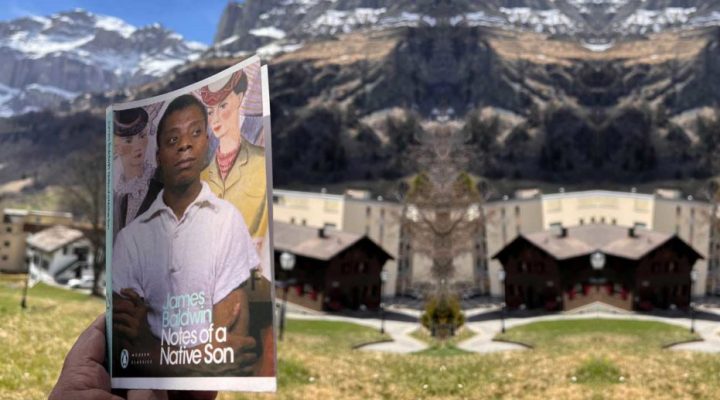

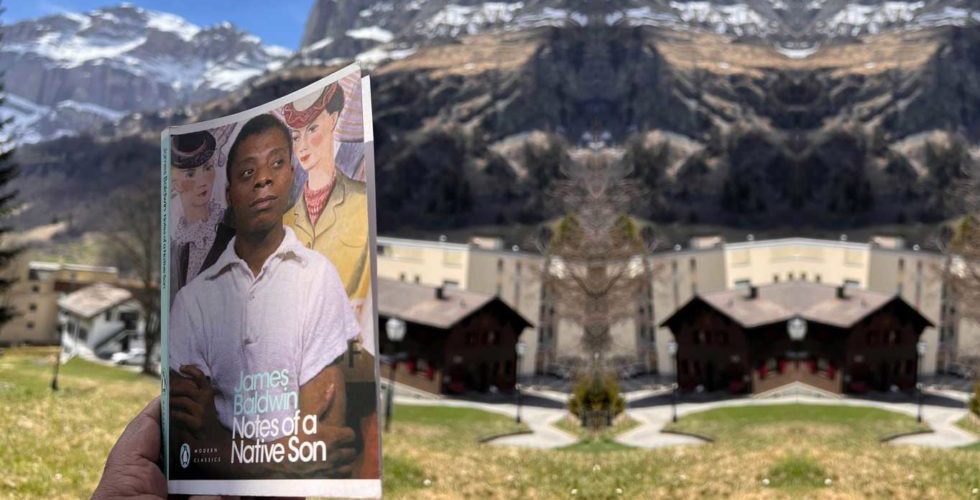

The idea of racial separation — that people belonged “where they came from” — seemed more real to Baldwin in Leukerbad than in the States. He was clearly an alien there, an outsider, visibly not “from” there. The seminal essay he wrote about his time in Switzerland and the conclusions to which it had moved him was actually called “Stranger in the Village” in its original publication in Harper’s and in his collection Notes of a Native Son.

The idea of racial separation — that people belonged “where they came from” — seemed more real to Baldwin in Leukerbad than in the States. He was clearly an alien there, an outsider, visibly not “from” there. The seminal essay he wrote about his time in Switzerland and the conclusions to which it had moved him was actually called “Stranger in the Village” in its original publication in Harper’s and in his collection Notes of a Native Son.

Other Americans, not all of them remembered as racists, have been moved to follow this logic that the races should be separated, that people could somehow go back to their ancestral homes. Even Abraham Lincoln, the Great Liberator, long thought that perhaps the solution was to return slaves to Africa. And certainly in recent days former President Donald Trump and his supporters vocally encouraged politicians with whom they don’t agree — who not coincidentally happen to be women of color — to go back where they came from (even though for many of them that is right here, as they were born in America).

“People are trapped in history, and history is trapped in them.”

But Baldwin’s conclusion when he came down from the Alps did not support the separation of the races, or the idea that Americans of any color could be sent back to the places from which they or their families came. America is a product of the melting pot of races and cultures, positive experiences and negative. This never can be changed.

“People are trapped in history,” Baldwin writes in “Stranger in the Village,” “and history is trapped in them.”

Just as Lincoln says of the North and South in his first inaugural address that “we cannot separate,” Americans of every creed and color and political persuasion and economic reality are tied together in the common experiment that is America, and no one can be extracted out of it because we disagree with them or hate them or fear them. What it means to realize that we cannot separate ourselves, Baldwin says, is that we are forced to reckon with the “other,” the person who doesn’t resemble us.

As an African American man, Baldwin put it like this: “The Black man insists, by whatever means he finds at his disposal, that the white man cease to regard him as an exotic rarity and recognize him as a human being.” But we can substitute for “Black man,” the Jew, the Muslim, the Salvadoran, the Asian, the trans woman, the person who doesn’t fit our ideas of how an American should look.

America cannot be dialed back to a time when only white Protestant Christian men were heard, however loudly or stridently some might long for that. In fact, as Baldwin points out, the very vehemence of the argument, the necessity, say, for a crowd at a Trumpian campaign rally to chant “Send them home,” implies “a certain unprecedented uneasiness over the idea’s life and power, if not, indeed, the idea’s validity.”

“America cannot be dialed back to a time when only white Protestant Christian men were heard.”

You can’t send them home, any more than any “white” American can be sent home. We are trapped in mutuality, in the need to acknowledge and understand each other. That easy and nonexistent solution is simply an emotionally satisfying racist chant, not a policy solution. Baldwin tells us that the person of color “is not a visitor to the West, but a citizen there, an American; as American as the Americans who despise him, the Americans who fear him.”

In our book-length conversation, Rowan Williams, the past archbishop of Canterbury and one of the world’s more formidable intellects, told me it is essential that we enter into dialogue with those we don’t understand or don’t like because “they are not going away.”

This was Baldwin’s conclusion, and after coming back from Leukerbad, mine as well. On the train back to Geneva, I sat across from a Muslim girl who was chatting excitedly on her phone, and just behind an Asian woman dressed to the nines although there was a heat wave across all Europe. I got off the train in Geneva surrounded by faces that did not look like my face, by people speaking languages I do not speak.

Even Switzerland, land of chocolate and cuckoo clocks and whiteness, is no longer a racial monolith, and only someone blind or willfully ignorant could fail to notice this.

“People who shut their eyes to reality simply invite their own destruction,” Baldwin concludes, “and anyone who insists on remaining in a state of innocence long after that innocence is dead turns himself into a monster.”

So Baldwin’s prophetic words remind us that people of color, Jews, Muslims, gays, opinionated women, whoever someone might think of as the undesirable who somehow reached our shores and need to be sent home to preserve American purity are not “them.”

They are us.

They are not going home.

They are home.

And it is our task to build an idea of America big enough to encompass us all.

Greg Garrett

Greg Garrett teaches creative writing, film, literature and theology classes at Baylor University. He is the author of two dozen books of fiction, nonfiction, memoir and translation, including the critically acclaimed novels Free Bird, Cycling, Shame and The Prodigal. He is one of America’s leading voices on religion and culture. One of his most recent nonfiction books is In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett. His latest book, A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation, is hot off the presses. He is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

Related articles:

Amid rampant antisemitism, most Americans think highly of Jews

A message to white Christian America: Remember the church at Sardis | Opinion by Wendell Griffen

Baldwin, Bobby and the necessity of hard conversations | Opinion by Greg Garrett