It was Holy Week and two young Black men, motivated by the courage of their Christian convictions, took part in a nonviolent demonstration. Colleagues chided them for their participation. It was “untimely” given the circumstances, they complained.

Furthermore, the young men had ignored the “proper channels” for change, instead taking “extreme measures” to make their point. A few days later, on April 16, 1963, awaiting bail in the city jail of Birmingham, Ala., one of those young men began writing an open letter addressing his critics and explaining the necessity of nonviolent protest.

Tennessee State Representatives Justin Jones and Justin J. Pearson are seen during a demonstration of linking arms in support of gun control laws sponsored by Voices for a Safer Tennessee at Legislative Plaza on April 18, 2023 in Nashville, Tennessee. Photo by Jason Kempin/Getty Images)

Sixty years later, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” inspired two young Black men in Nashville, Tenn., to flout the rules of decorum and demand justice for victims of gun violence.

Today’s Tennessee would look sadly familiar to King.

Josh Spickler

“The legacy of segregation impacts so much in the South and in Tennessee. Our prisons and jails are disproportionately Black. Health outcomes are worse for Black people. Educational experiences vary wildly by ZIP Code and are hardly ever better in the ones with the most Black children,” according to Josh Spickler of the nonprofit Just City. “And we perpetuate (these dispartites) with the same systems, rules and norms that we’ve always used.”

A white conservative supermajority

In modern-day Tennessee, the central power is the predominantly white, conservative, Republican Party that controls the executive and judiciary branches of government and holds a supermajority in the state legislature.

A simple majority is a narrow enough margin that debate, protest, petition or the free press may still influence either party and shape the legislative outcome, but a supermajority can ignore opposing opinions. This lopsided representation in Tennessee controls the entire legislative agenda and determines which laws are passed and which are tabled, if debate is entertained or extinguished, and how the state House and Senate are governed.

“The Republican supermajority is the result of some heavily gerrymandered redistricting by the party.”

The Republican supermajority is the result of some heavily gerrymandered redistricting by the party, designed to dilute the power of Democrats and their minority voters. While receiving a third of the vote in statewide elections, Democrats hold only 24 of the 99 state House seats and six of the 33 seats in the state Senate. Half the Republican candidates running for the Tennessee House in 2022 faced no opposition, while Democratic incumbents’ districts were combined to reduce their numbers.

Covenant School murders

That set the stage for what happened after a gunman fired 152 rounds at the staff and students of Covenant School, a private Christian school in Nashville, killing three adults and three children. Parents, students and advocates gathered at the Capitol to demand action on gun control.

Alexander Reddy, 17, prays at an entry to Covenant School, Tuesday, March 28, 2023, in Nashville, Tenn., which has become a memorial to the victims of Monday’s school shooting. (AP Photo/John Amis)

Tennessee ranks No. 11 nationwide for gun violence and experienced a 48% increase in gun deaths from 2011 to 2020. The state has some of the least restrictive gun laws in the country, and Republican lawmakers were not inclined to change them after the Covenant School shooting.

“Political power is deeply seated in parts of this state that have absolutely no interest in sensible gun regulations,” Spickler explained.

Having campaigned on the NRA-approved permitless carry of loaded guns, Gov. Bill Lee said now was not the time to discuss gun policy. His fellow Republicans in the Senate temporarily halted progress on all gun legislation for the remainder of the year, even a bill requiring safe firearms storage. House Republicans, meanwhile, had no compunction about continuing work on bills to lower the permitless carry age to 18 for all weapons and to arm teachers, even though some staff members at Covenant were armed at the time of the attack.

Three days after the mass shooting, on March 30, hundreds more marched on the Capitol, imploring lawmakers to pass gun-control legislation. Holding signs and wearing orange, they filled the halls and galleries of the Legislature.

No interest in hearing

Their pleas fell not on deaf ears, but on the ears of the supermajority in their electorally secure seats.

David Weatherspoon

“As the father of 9- and 6-year-old girls, I’m furious at the inaction of legislators,” said David Weatherspoon, a chaplain in Memphis and former candidate for the Tennessee Senate. “Decisions and calculations by the GOP have been made that see guns as a means to maintain their power and control at the expense of human lives, including children.”

“Decisions and calculations by the GOP have been made that see guns as a means to maintain their power and control at the expense of human lives, including children.”

On March 30, Democrat representative Justin Pearson repeatedly tried to steer debate to the recent mass shooting, but Speaker of the House Cameron Sexton — a Southern Baptist layman — quashed his attempts and turned off his mic. Sexton then reprimanded Rep. Justin Jones of Nashville for wearing a pin that said, “Halt the Assault,” even though others in the house frequently wear NRA pins.

When Jones raised this point, his voting machine was turned off.

As the House’s Republican members continued to ignore protesters, Pearson and Jones, along with fellow Democratic Rep. Gloria Johnson of Knoxville, felt compelled to act. Pearson later wrote in a letter to the House: “When I saw thousands of people — mostly children and teenagers — protesting and demanding action from us after the slaying of six innocent people, including three 9-year-old children, it was impossible to sit idly by and continue with business as usual.”

The trio, now known as the “Tennessee Three,” walked to the front of the room, known as the well of the House, to force a discussion on gun control legislation. Speaker Sexton called for a recess and turned off the podium microphone, so Jones and Pearson used a megaphone to address their fellow representatives on the floor and the protesters in the balcony. Johnson stood with them in solidarity and joined in as they led the protesters in chanting, “No justice, no peace!” and “Whose house? Our house!” and “Gun control now!”

“We occupied the House floor today after repeatedly being silenced from talking about the crisis of mass shootings.”

Jones tweeted after the event: “There comes a time when you have to do something out of the ordinary. We occupied the House floor today after repeatedly being silenced from talking about the crisis of mass shootings. We could not go about business as usual as thousands were protesting outside demanding action.”

Creating tension

This is the same reasoning Martin Luther King Jr., and his fellow protesters employed 60 years ago. As King explained in his letter, sometimes actions out of the ordinary are necessary: “Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored.”

Justin Jones (Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call via AP Images)

Creating tension is something Rep. Justin Jones learned firsthand from civil rights leader John Lewis. In 2016, Jones spent the summer working in Washington, D.C., and saw Lewis lead a 25-hour sit-in calling for common-sense gun legislation after the massacre at Pulse nightclub in Orlando.

When he returned to Tennessee, Jones led a 61-day sit-in at the Capitol to demand a meeting with the governor on racial inequality and police brutality. Jones and those with him also called for the removal of a bust of a slave trader and KKK leader from the building.

Jones lives by Lewis’ wisdom that “when you see something that is not right, not fair, not just, you have to find a way to get in the way,” he said in a 2022 campaign interview. “To get in ‘good trouble, necessary trouble.’”

A community organizer as well as a divinity student at Vanderbilt University, Jones was elected last November to represent District 52 in Nashville, where a different mass shooting occurred at a Waffle House in 2018.

Rep. Pearson not only shares a first name with Jones, but also his Christian faith and belief in the nonviolent methods of King. Pearson‘s father is pastor at Community Faith Christian Church in Memphis, and Pearson himself has spoken from the pulpits of several area churches. He is best known as a grassroots organizer for his efforts to end construction of the Byhalia Connection crude oil pipeline that threatened local drinking water.

Justin Pearson (Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images)

When House District 86 held a special election in January to fill the seat previously held by Rep. Barbara Cooper, Pearson won in a landslide.

“Justin ran a great campaign and showed that with the commitment to community change, you can defeat a whole bevy of names on the ballot,” said Cardell Orrin, executive director of the nonprofit Stand for Children in Memphis. “I’ve had the opportunity to engage with a lot of candidates over the years, and Justin is in the top tier for many reasons.”

Sexton and Republican members of the House criticized Pearson at his swearing in ceremony for breaking “decorum rules” by wearing a traditional African dashiki instead of a suit and tie.

Anniversary of King’s assassination

On April 4, the 55th anniversary of King’s assassination, Pearson spoke at a remembrance service at the National Civil Rights Museum established at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. There he said: “In persecution, the good news of the Christian faith is there’s always resurrection. Even in a place like this where an assassin’s bullet thought they might destroy a justice movement, justice still springs forth.”

“In persecution, the good news of the Christian faith is there’s always resurrection.”

That same day in Nashville, the General Assembly permanently halted action on any gun legislation until 2024, and Speaker Sexton took aim once more at the movement. Speaking with a local reporter, Sexton said the Tennessee Three should be expelled from the House for “breaking every rule we almost have — props, how they act, decorum” and “trying to jazz people up.”

Tennesee House Speaker Cameron Sexton, R-Crossville, says the Pledge of Allegiance during a special session in 2021, in Nashville, Tenn. (AP Photo/Mark Humphrey)

While the Tennessee Constitution makes no mention of “jazzing people up,” Section II Article 27 does say members “shall have the liberty to dissent from and protest against any act or resolve which he may think injurious to the public or to any individual.”

When asked about this provision, Republican Rep. Mark White said, “When a member brings that dissent to the level of overtaking the House and cutting off civil debate and endangering the safety of others on the floor and inciting protesters, that cuts off our ability to do business (and) is not acceptable.”

Whose business?

Which raises the question: “Whose business are they doing?”

Certainly not the protesters’, who are also constituents. And Speaker Sexton already had shut down’ attempts at “civil debate” by cutting off the microphone.

“Pearson, Jones and Johnson were actually representing many of us who believe we need better gun regulations,” Weatherspoon said. However, the supermajority controls every aspect of the agenda and, so far, has refused to discuss meaningful gun control.

“To expel these three legislators is an immoral and unethical attempt to silence the opposition,” Weatherspoon added. The entire General Assembly, like King’s “beloved Southland” in 1963 is “bogged down in a tragic effort to live in monologue rather than dialogue.”

In his “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” King considers a citizen’s obligation to obey an unjust law.

“An unjust law is a code that a numerical or power majority group compels a minority group to obey but does not make binding on itself.”

“An unjust law,” he wrote, “is a code that a numerical or power majority group compels a minority group to obey but does not make binding on itself.” Such is the case with the Tennessee Legislature’s so-called rules of “decorum.”

When then Republican state senator Marsha Blackburn summoned a right-wing mob of 2,000 to the Tennessee Capitol in 2001 with the email subject “TIME FOR TROOPS,” she was not expelled, even though protesters threw rocks, banged on doors and broke windows. Republican Rep. Justin Lafferty violated decorum rules by recording a video of the March 30 demonstration by the Tennessee Three with his phone. Lafferty was not expelled or censured. Instead, his highly edited video was used as evidence in the expulsion hearing of Jones, Johnson and Pearson.

Expulsion an extreme measure

Expulsion is rare in the Tennessee House of Representatives. The body expelled six members in 1866 for refusing to ratify the 14th Amendment, granting citizenship to formerly enslaved persons. In 1980, Rep. Robert Fisher was expelled for accepting a $1,000 bribe while in office. In 2016, the House expelled Rep. Jeremy Durham for sexual misconduct. The attorney general of Tennessee, in a 2019 review of the expulsion process, stated that expulsion must be “exercised only in extreme circumstances and with great caution.” The Tennessee Constitution states that each house of the General Assembly may determine its own definition of “disorderly behavior.” However, their rules cannot contradict the U.S. Constitution and must consider due process, equal protection and the people’s right to choose their own representatives.

“They were trying to expel us for a protest, but they weren’t talking about the conditions that brought us to the well to protest in the first place.”

To prepare for the hearing, Jones consulted “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” In an interview with MSNBC, Jones said, “Dr. King wrote, ‘You deplore the demonstrations that are taking place in Birmingham but you have not expressed similar concern about the conditions that brought the protests into being in the first place.’ And as I thought about being expelled, I thought they were trying to expel us for a protest, but they weren’t talking about the conditions that brought us to the well to protest in the first place … the conditions (being) that we worship guns at the expense of our children.”

Gun deaths are the No. 1 killer of children ages 1 to 19 in America today. Including the shooting at Covenant School, 74 people have been killed or injured in school shootings thus far in 2023. The total last year was 303.

Keeping Black men in their place

House Republicans conducted the expulsion hearing for Jones, Johnson and Pearson like a trial. Sexton previously railed in tweets and on talk radio that the demonstration in the Tennessee House was potentially worse than the violent insurrection on January 6 at the U.S. Capitol, stoking the racist stereotype that Black men are inherently dangerous. This hyperbole continued at the hearing and would have been laughable, were it not for the racism and condescension oozing from each accusation.

“The language the state House leadership used last week to expel two Black men was couched in terms of respect, decorum and authority, echoing generations of white men whose power and very existence depend upon Black men staying in their proper place,” Spickler said.

Andrew Farmer

Rep. Andrew Farmer, the Republican who pushed for expulsion, said Pearson threw a “temper tantrum with an adolescent bullhorn.” Speaker Sexton belittled the nonviolent methods employed by the Tennessee Three as selfish, saying (without any hint of irony) they were taking focus away from the shooting victims.

When given a chance to defend their actions, the Tennessee Three seized the opportunity to lobby for gun control.

“There’s one common denominator: It’s the guns.”

“I’ve spent my life dedicated to helping children,” said Johnson, a former special education teacher who lost a student in the 2008 Central High School shooting in Knoxville. “There are so many things we could do to change the trajectory of where we’re headed: more school shootings, church shootings, theater shootings, Waffle House shootings. It’s happening everywhere, folks. There’s one common denominator: It’s the guns.”

Rep. Jones read from Jeremiah 6:14 as he addressed the House members about the recent gun deaths: “They offer superficial treatments for my people’s mortal wounds. They give assurances of peace where there is no peace.”

Pearson argued America was built on protest and those in his district supporting him were being expelled as well. “Because you spoke up for people who are marginalized. You spoke up for children who won’t ever be able to speak again. You spoke up for parents who don’t want to live in fear, you spoke up for Larry Thorn, who was murdered by gun violence. You spoke up for people we don’t want to care about. In a country built on people who speak out of turn, who spoke out of turn, who fought out of turn to build a nation.”

After each defendant finished speaking and after hours of questioning and debate, members cast their votes. Former lawmaker John Mark Windle, who defended Johnson, observed: “Today is Maundy Thursday, the day of betrayal. Isn’t it fitting these allegations are made during Holy Week?”

When it was time to vote, seven Republicans sided with House Democrats and voted against expelling Johnson, saving her by one vote. Jones and Pearson were not so fortunate. The Republican supermajority voted to expel them both.When asked why she was spared while her colleagues were expelled, Johnson said it “might have to do with the color of my skin.”

“There is a deep-seated fear particularly of young Black men who speak powerfully and prophetically about societal issues that need to change.”

Weatherspoon agreed: “There is a deep-seated fear particularly of young Black men who speak powerfully and prophetically about societal issues that need to change. Even in a state legislature with a GOP supermajority. They guise their fear in ‘decorum’ and ‘rules of conduct’ (but) they are terrified of the voices of young Black men.”

A dangerous precedent

What happened in Tennessee sets a dangerous precedent. Observers wonder if other states with supermajorities in their legislatures, like Wisconsin and North Carolina, will follow Tennessee’s lead and expel the opposition.

“America should be worried,” Johnson said. Jones, talking to reporters after his expulsion, told those gathered: “If we don’t act, we have some very dark days ahead. We have to respond to this with mass movements, nonviolent movements. This should sound the alarm across the nation that we are entering into very dangerous territory.”

Standing up to the supermajority and the power brokers in Tennessee may have cost Jones and Pearson their jobs for a moment, but both members of the House were determined it would be the people and not the politicians who would have the last say.

“Sometimes you have to … demand that democracy be true for everybody, not just for rich white men in suits, not just for rich white people who got these positions of power perpetuating the status quo, not just those who are being supported by the NRA,” Pearson said. “The folks in our districts get a voice too.”

Remembering the events of another Holy Week, he said, “Jesus, a man who was innocent of all crimes except fighting for the poor, fighting for the marginalized … was lynched by the government on Friday. … On Saturday, all hope seemed to be lost. I don’t know how long this Saturday in the state of Tennessee might last, but we have good news, folks. We’ve got good news that Sunday always comes. Resurrection is a promise.”

Taking King’s mantle

Jones and Pearson may be a generation removed from King, but they have seized upon his legacy and donned the mantle of nonviolent resistance in a way rarely seen in Tennessee since King marched there himself in the 1960s.

Having grown up in the era of the Black Lives Matter movement, Jones and Pearson draw their inspiration from their Christian faith and the writings of King.

King and Ralph Abernathy were arrested in Birmingham on Good Friday 1963, and there’s a sense of loneliness, abandonment and betrayal in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail” that mirrors Christ’s own. The Civil Rights movement in Birmingham had started off well with boycotts of businesses, sit-ins at lunch counters, and a voter registration march. Then the city obtained an injunction from the state circuit court against the protests.

“The movement needed King to fundraise, but his credibility was on the line if he didn’t act against this unjust court order.”

King was in a difficult position. Earlier demonstrations had depleted the fund for cash bonds, so there was no guarantee those arrested for nonviolent action would be released. The movement needed King to fundraise, but his credibility was on the line if he didn’t act against this unjust court order.

King had hoped white moderate Christians would rise up and join the fight for freedom. Instead, he found them to be a great “stumbling block,” a group “more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice.”

When Rep. Jones first joined his Democratic colleagues in the Tennessee House, he was encouraged to “keep his head down” and “to assimilate, to conform.” After all, the Republican Party had a supermajority in the House that completely controlled the legislative agenda. The best Democrats could hope for was to “go along to get along” and get what they could for their constituents back home.

“There’s always a time to protest and there’s a certain way you can do it, but in any environment you go into, you must know the rules,” said fellow Democratic Rep. Joe Towns Jr.

On March 30, when Jones, Johnson and Pearson joined protesters to call for gun control laws, Towns and Minority Leader Karen Camper angrily ushered them from the well of the House. Jones and Pearson were later expelled for their actions while Johnson was saved from expulsion by one vote.

Johnson as a white ally

Had she been expelled, Johnson would have lost her health insurance and, because the Knox County Commission has a Republican majority, would have had to wait until a special election to run again for her seat. Even so, Johnson said it was difficult to feel positive about her own survival when her two colleagues had been expelled. “They showed today how brilliant they are, how important their message is for the next generation to be able to connect like they can to the people.”

“When she did not vote to re-elect Cameron Sexton as Speaker of the House, Sexton retaliated by moving her office to a tiny windowless room.”

Johnson herself is no stranger to protest and fighting an uphill battle. When she did not vote to re-elect Cameron Sexton as Speaker of the House, Sexton retaliated by moving her office to a tiny windowless room and moving her assistant into an unventilated closet. To draw attention to the situation, Johnson moved her desk out into the hallway.

Gloria Johnson (Photo by Ken Cedeno/Sipa USA via AP Images)

In her actions and attitude, Gloria Johnson embodies the inversion of the power structure liberation theologian Allan Boesak says is necessary for true racial reconciliation to occur. She is the kind of white, moderate ally King sought in his letter, but who too often failed to show up for the Civil Rights movement.

“Few members of the oppressor race can understand the deep groans and passionate yearnings of the oppressed race, and still fewer have the vision to see that injustice must be rooted out by strong, persistent and determined action,” King wrote.

For change to happen, those in positions of power and privilege must be made, or be willing to become, uncomfortable.

“From my perspective as an affluent, middle-aged white man, I think that means speaking to my contemporaries about the white supremacist underpinnings of the criminal legal system,” said Spickler of the Memphis nonprofit Just City. “It was built to protect our privilege and has a direct connection to other, more explicit systems like slavery, Jim Crow, red-lining, etc. White people still need to confront this truth, and it is incumbent on some of us to do that, as uncomfortable as that may be.”

Sowing discomfort was at the heart of the House protest by the Tennessee Three, and the unwillingness of Republicans to face the truth led to Jones’ and Pearson’s expulsions.

Sent back to keep fighting

When a seat in the General Assembly becomes vacant and the next general election is more than a year away, the district they represent holds a special election to choose a new representative. In the intervening time before the special election, the district council appoints an interim to fill the seat. Normally there’s a four-week wait, but Nashville Vice Mayor Jim Shulman began working immediately after Rep. Jones’ expulsion on Maundy Thursday to appoint Jones as his own replacement. Flights were changed and vacations canceled so the Metropolitan Council of Davidson County would have the necessary numbers for an Easter Monday meeting. Corralling the necessary 21 votes was the next step.

Emails poured in over Easter weekend calling for Jones’ appointment as interim. “I was proud to see Justin Pearson and Justin Jones stand up for themselves at the Tennessee Legislature today backed by all their supporters from across the state and country,” said Cardell Orrin, executive director of the nonprofit Stand for Children in Memphis. “These young brothers will lead us to a better future.”

While the majority of the Metro Council are Democrats, there are a few conservative members. If two opposed lifting the four-week wait time, the legislative session would end and the District 52 seat would be left unfilled. Fortunately for Jones, those who might have opposed the motion did not attend the Monday meeting where a unanimous vote appointed Jones as the interim representative.

Reflecting on the story of Joseph in the Hebrew Bible, Jones said of Speaker Cameron Sexton, “What you meant for evil is being used for good to shine a light in this capital.”

The Metropolitan Council of Davidson County itself has been the object of Republican retribution. Lawmakers in the General Assembly attempted to cut the number of seats on the council from 40 to 20 after the Metro Council blocked the national Republican Party from holding its 2024 convention in Nashville.

The 40-seat council was the work of Civil Rights advocates who in 1963 fought to maintain the city-county structure that gave Black residents in Nashville a voice. Stripping the council to 20 seats would drastically impact the body’s diverse representation. Currently, a fourth of the council members are Black, half are women, and five are members who identify as LGBTQ.

“Tennessee Republicans sent out a fundraising email mail to cash in on the Democrat’s expulsion.”

On Good Friday as Democratic council members in Nashville scrambled to organize their meeting to appoint Jones, Tennessee Republicans sent out a fundraising email to cash in on the Democrat’s expulsion.

“Their adolescence and immature behavior brought dishonor to the Tennessee General Assembly,” the email said. “We applaud House Republicans for having the conviction to protect the rules, the laws and the prestige of the State of Tennessee.”

It ended with the cryptic words, “The fight is just beginning.”

The fact that Jones and Pearson did not break any laws is beside the point to those on the far right, who called their protest an “insurrection,” Weatherspoon said. “It is ironic given the differences in events. Peaceful protests against a deep injustice in gun violence versus the real insurrection in the violent act of treason on January 6 by many of the same base for these GOP politicians.”

Julian Bond

This is not the first time a state legislature has undermined the will of the people by targeting their African American representative. In 1966, the Georgia Legislature refused to swear in Julian Bond. Just as with Pearson and Jones, the actions against Bond were racially motivated, a violation of the First Amendment and a denial of his constituents’ right to choose their representative.

“If you’re going to be a Christian, take the gospel of Jesus Christ seriously, you must be a dissenter, you must be a non-conformist.”

Originally from Nashville, Bond was a Civil Rights activist who opposed the Vietnam War. One of Bond’s constituents was Martin Luther King Jr. On April 16, 1966, three years to the day of his arrest in Birmingham, King praised Bond in his Sunday sermon at Ebenezer Baptist Church, saying he was “a young man who dared to speak his mind.” King continued, “If you’re going to be a Christian, take the gospel of Jesus Christ seriously, you must be a dissenter, you must be a non-conformist.”

Bond went on to serve in the Georgia House and Senate and co-founded the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Taking the gospel seriously

Taking the gospel seriously means being an “extremist,” King says in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” An extremist for love like Christ who told his followers to “love your enemies,” and an extremist for justice like Amos who called for justice to “roll down like waters.”

As the Civil Rights movement progressed, King himself became more extreme. He spoke out against the Vietnam War and the nation’s tendency toward imperialism. In 1967, he launched the Poor People’s Campaign that focused on jobs, a fair minimum wage, unemployment insurance and education for poor adults and children. The campaign was more assertive in its socioeconomic demands and more pointed in its political critiques.

In response, the Civil Rights movement’s liberal, white supporters began to bow out and took their donations with them. The Poor People’s Campaign separated King’s followers from his fans.

“Being an extremist for justice is what prompted King to join Memphis’ sanitation workers who were striking in 1968.”

Being an extremist for justice is what prompted King to join Memphis’ sanitation workers who were striking in 1968. The men who collected the city’s garbage were treated like little more than garbage themselves. They were among the poorest of the poor, making 65 cents an hour and subjected to horrendous working conditions.

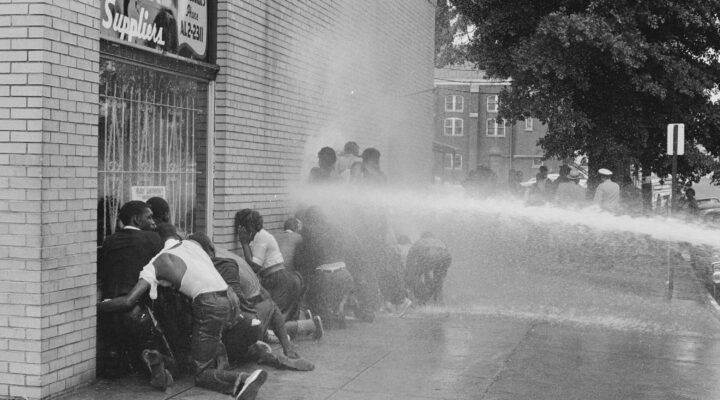

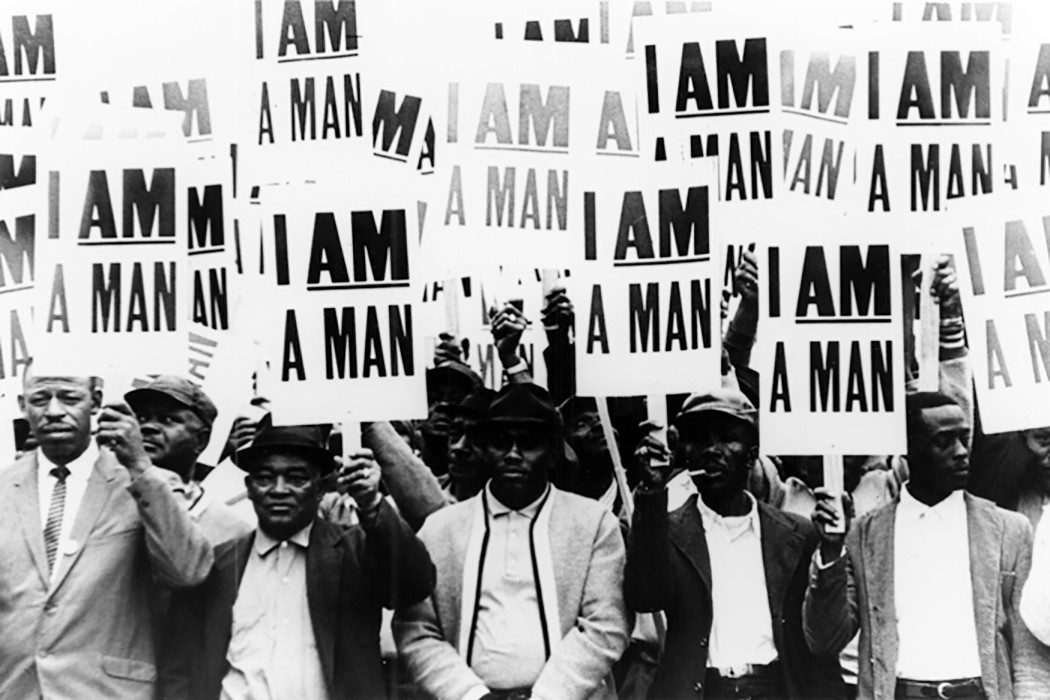

In February that year, two workers were killed when their truck malfunctioned and the city refused to compensate their families. It was just the sort of injustice King wanted to highlight in the campaign. Five thousand protesters marched with him in Memphis, many carrying signs that read “I AM A MAN, “a precursor to the phrase “Black Lives Matter.”

Striking members of Memphis Local 1733 hold signs whose slogan symbolized the sanitation workers’ 1968 campaign. (Via Walter P. Reuther Library/Wayne State University)

The march erupted in violence and looting. Police chased and gunned down an unarmed 16-year-old boy. They flung tear gas at protesters seeking refuge in a neighborhood church and beat them as they lay on the floor inside. King was determined nonviolence would have the last word. “The movement lives or dies in Memphis,” he said as he prepared for a second march.

He stood in the pulpit of Mason Temple on April 3 and spoke about his time in Birmingham and the tactics of Bull Connor: “There was a certain kind of fire that no water could put out. And we went before the fire hoses; we had known water. If we were Baptist or some other denominations, we had been immersed. … That couldn’t stop us.”

He told those gathered about the jail where he wrote his famous open letter to local clergy and moderate critics: “We’d see the jailers looking through the windows being moved by our prayers and being moved by our words and our songs. And there was a power there which Bull Connor couldn’t adjust to.”

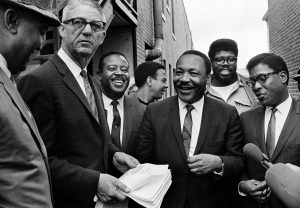

U.S. Marshal Cato Ellis serves Martin Luther King and his aides with a temporary restraining order barring them from leading another march without court approval, outside the Lorraine Hotel in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 3, 1968. The order was aimed at stopping a march set for April 8 in support of city sanitation workers. Identified people in the photo are Cato, holding papers, Ralph Abernathy, Andrew Young, in profile and Kin. Others are unidentified. (AP Photo)

King reminded the preachers in his audience once more to live and minister like Amos, that “extremist for justice” who said, “Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like a might stream.” He preached then on the Parable of the Good Samaritan and the necessity of developing a “dangerous unselfishness.” Rather than asking, “If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?” the Good Samaritan asked, “If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?”

King then posed the question, “If I do not stop to help the sanitation workers, what will happen to them?”

There was a second march in Memphis, but King was not there to lead it. He was assassinated on April 4, 1968, at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis.

Back to Memphis

Fifty-five years and one week later — on April 12, 2023 — Justin Pearson, Justin Jones and Gloria Johnson gathered with hundreds of supporters outside the Loraine Motel, now the National Civil Rights Museum. Pearson began his remarks by quoting King, “The movement lives or dies in Memphis, and here at this hallowed place, at this sacred place, we’re showing the United States of America and the Republicans in Tennessee that the movement is still alive.”

Johnson encouraged the audience to “lift up the voices of young people.” Jones called for Speaker Sexton to resign and then handed the microphone back to Pearson.

“This is the democracy that is going to transform a broken nation and a broken state and transform it into the place that God calls for it to be,” Pearson said. “This is the democracy that will bring people from the back, people that have been pushed to the periphery to the center of justice.”

After the speech, the Tennessee Three and those gathered at the museum marched more than a mile to the Shelby County Commission building where the Shelby County Board of Commissioners was holding a special meeting to vote on installing Pearson as the interim representative of District 86. The marchers sang “Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me around …, Ain’t gonna let white supremacy turn me around” as they made their way to the meeting.

Pearson’s father, Pastor Jason Pearson, opened the meeting with prayer and the board quickly voted 7-0 to appoint Justin Pearson to fill the position from which he had been expelled.

If King were writing his “Letter from Birmingham Jail” now, a letter from Memphis or Nashville, what would he say?

Josh Spickler has an idea: “He would write the exact same letter with the same focus on the same white people, who are seemingly much less moderate in Tennessee these days but are still more devoted to order than justice.”

David Weatherspoon agrees that King would be saddened to find so much of America unchanged. “He would be steadfast in his understanding that the work is still so similar to what he wrote in the Birmingham jail. But I also believe he’d be a bit dismayed and angry that we are still in a spot that is so similar to 60 years ago when he wrote that letter. … I also think he’d be proud of Jones and Pearson.”

Kristen Thomason is a freelance writer with a background in media studies and production. She has worked with national and international religious organizations and for public television. Currently based in Scotland, she has organized worship arts at churches in Metro D.C. and Toronto. In addition to writing for Baptist News Global, Kristen blogs on matters of faith and social justice at viaexmachina.com.

Related articles:

Expelling dissent: America from Roger Williams to the ‘Tennessee Three’ | Opinion by Bill Leonard

Tennessee legislators turn back the clock to Jim Crow time | Opinion by Rodney Kennedy

Hypocrisy | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

Tennessee representative who proposed execution by ‘hanging by a tree’ needs a history lesson | Opinion by Rodney Kennedy

Dear Tennessee legislators: You are driving people away from faith | Opinion by Brad Bull