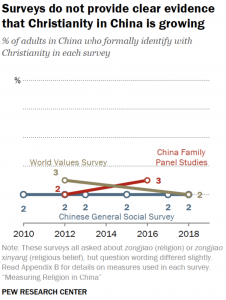

The growth of Christianity in China has remained flat for more than a decade, according to polls conducted in the Communist nation and analyzed by Pew Research Center.

“Christianity flourished after China entered an era of economic reforms and ‘opening up’ to the world in the 1980s. But recent surveys that measure zongjiao (religious) affiliation do not offer much evidence that Christian growth continued after 2010,” Pew said in an analysis titled “Measuring Religion in China.”

The Chinese General Social Survey found about 23 million Chinese self-identified as Christians in 2010, compared to about 20 million who did so in 2018 — a statistically insignificant dip, Pew said.

The Chinese General Social Survey found about 23 million Chinese self-identified as Christians in 2010, compared to about 20 million who did so in 2018 — a statistically insignificant dip, Pew said.

“According to this survey, Protestants account for roughly 90% of Chinese Christians, or about 18 million adults, while the remainder are mostly Catholics. Smaller groups, which include Orthodox Christians, are fewer than 1% of Christian adults in China.”

The Chinese social survey also found Christian practices have peaked. “Among those who identify as Christian, reports of zongjiao (religious) activity levels are roughly stable. In 2010, 38% of Christians said they engaged in zongjiao activities at least once a week, while in 2018, 35% said so — a difference that is not statistically significant.”

When the 2018 World Values Survey asked Chinese adults if they “believe in” Christianity, 2%, or about 20 million, said they did. The China Family Panel Studies survey reported in 2016 that 3% of Chinese reported that they “belong to” Christianity.

“Some media reports and academic papers have suggested the Christian share may be larger, with estimates as high as 7% (100 million) or 9% (130 million) of the total population, including children. No national surveys that measure formal Christian affiliation — by asking people which religion (zongjiao) they identify with — come close to these figures,” according to the Pew report.

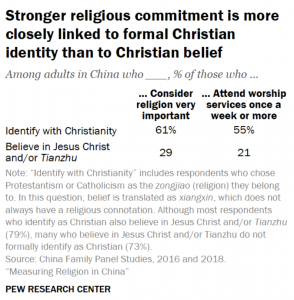

Some surveys suggest greater numbers of Chinese are connected to Christianity when measured by belief instead of religious self-identification or practice, Pew explained. “For example, the cumulative share of Chinese adults who say they ‘believe in’ (xiangxin) Jesus Christ and/or Tianzhu (the word Chinese Catholics use for God) is 7%, or roughly 81 million adults, according to the 2018 (China Family Panel Studies) survey. Some scholars argue that this measure may be a better alternative than zongjiao xinyang (religious belief), citing a core Christian teaching that one should never deny belief in God (including Jesus Christ or Tianzhu) regardless of the circumstances.”

Survey questions about formal religious affiliation often uncovered a subset of Christians with deeper levels of commitment to Christ, Pew said. “According to data from the 2016 and 2018 (China Family Panel Studies) surveys, 68% of adults who self-identify as Christians believe in Jesus Christ and/or Tianzhu (God) exclusively (i.e., without believing in other deities, including Buddha and/or a bodhisattva, immortals or Allah).”

Survey questions about formal religious affiliation often uncovered a subset of Christians with deeper levels of commitment to Christ, Pew said. “According to data from the 2016 and 2018 (China Family Panel Studies) surveys, 68% of adults who self-identify as Christians believe in Jesus Christ and/or Tianzhu (God) exclusively (i.e., without believing in other deities, including Buddha and/or a bodhisattva, immortals or Allah).”

The Chinese government occasionally publishes its own statistics, which report the number of Protestants has grown from 700,000 in 1949 to 38 million in 2018. “However, the 1949 and 2018 numbers do not seem to be directly comparable, because the Chinese government has changed its sourcing and methodology without making appropriate adjustments, and it does not always state whether children are included,” Pew countered.

Furthermore, the Chinese general survey found the number of Protestants decreased from 21 million in 2010 to 18 million in 2018.

China’s Catholic population seems to have stagnated, Pew added. According to government figures, affiliation with the church remained steady at approximately 6 million from 2010 to 2018. The Chinese social survey, on the other hand, reported 3 million Catholics in 2010 and 2 million in 2018.

Pew warned that none of the statistics it analyzed can be taken as definitive, including those reporting the devotion some Chinese Christians have for Jesus. “These figures encompass those who also believe in one or more non-Christian deities, such as Buddha and/or a bodhisattva, immortals (Taoist deities) or Allah. The share of Chinese adults who say they believe in Jesus Christ and/or Tianzhu (God) and do not believe in these other deities is about 3%.”

Conventional polling often overlooks the nature of religious imagination and experience in China, the report said. “And even though Christianity and Islam, unlike Buddhism or folk religions, emphasize exclusivity in belief and practice, many Chinese who engage in Christian practice or even consider themselves to be worshippers of Jesus Christ or Tianzhu (God) may not necessarily identify with Christianity when asked about their zongjiao Xinyang (religious beliefs).”

The Chinese government also contributes to the difficulty researchers face in obtaining accurate data on religious people and groups, Pew said. “Officially, only churches authorized by the government are allowed to operate. But, in reality, many Christians worship in unauthorized venues known as ‘underground churches’ or ‘house churches.’ These Christians may be reluctant to reveal their identity.”

The Chinese government also contributes to the difficulty researchers face in obtaining accurate data on religious people and groups, Pew said. “Officially, only churches authorized by the government are allowed to operate. But, in reality, many Christians worship in unauthorized venues known as ‘underground churches’ or ‘house churches.’ These Christians may be reluctant to reveal their identity.”

Members of the Chinese Community Party are unlikely to identify as Christians for fear of retribution, Pew researchers added. “Unfortunately, we cannot be certain how survey patterns are affected by political circumstances. There could be a real increase in the share of Chinese adults who identify with Christianity that is hidden from survey measurement.”

Geography is another impediment facing researchers. “Roughly a quarter of China’s Catholics live in the northern province of Hebei, and they tend to cluster in rural ‘Catholic villages,’ where the vast majority of residents follow Catholicism. As a result, Catholic survey estimates may vary depending on how many such villages are included in the sample. Similarly, it is consequential whether Protestants are proportionately represented.”

The infrequency with which some surveys are conducted also can affect the reliability of data, Pew said. “Since measures of Christian belief and practice have not been repeated consistently in surveys, we cannot track how beliefs and practices associated with Christianity have changed since 2010 in the Chinese public. We don’t know, for example, whether overall belief in Jesus Christ or attendance at Christian worship services has risen, declined or remained stable.”