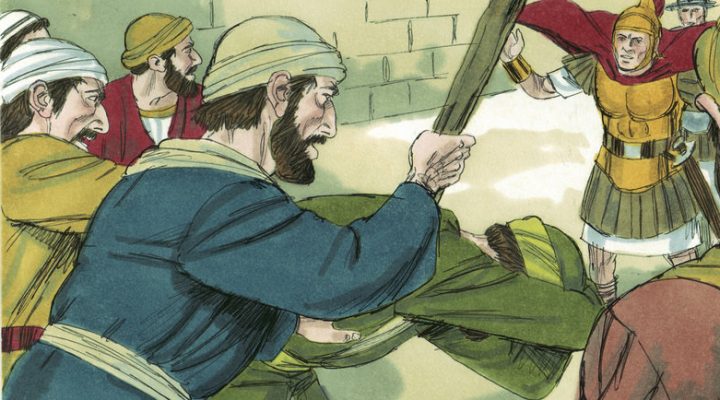

They “drove them out.” That’s what the book of Acts says a certain religio-political contingent did to Paul and Barnabas in Antioch of Pisidia, a crossroads of Roman-controlled towns in first century Asia Minor. As the text tells it, they expelled them because the Jews were “filled with violent resentment and contradicted what Paul and Barnabas said with violent abuse.”

Of course, they did. For those orthodox religionists, Paul and Barnabas were sell-outs, believers who knew better, but were reinterpreting the story, trying to blend irreconcilable world views, promoting an alternative theology. The prime perpetrator, Saul/Paul, whatever he called himself, was a Pharisee from Jerusalem, a rabbi born and bred in the texts and liturgies of synagogue and temple. He promoted that Mosaic identity and ideology for years; now he’s found another. Action must be taken.

Ultimately, that Pisidian controversy went political. It incited “the devout women of high standing and the leading men of the city, and stirred up persecution against Paul and Barnabas, and drove them out of their region.” At the intersection of politics and religion, “violent abuse” prevailed.

On his way out the door, Paul waxed eloquent about the “light to the Gentiles” he believed is dawning on the world, but did not soften his rhetoric toward the Jews, declaring “since you folks judge yourselves unworthy of eternal life, we are going to the Gentiles.” He and Barnabas shook the dust off their feet, literally, a poignant sign of a graceless embarkment.

As 2024 emerges, shouldn’t we avoid this troublesome text (Acts 13:44-52), perhaps rushing to Easter shouting, “He is risen!” or to Pentecost with the Holy Spirit poured out on “all flesh,” moments when the church seemed discernably “of one accord?”

Conflicts rage across our world, not just between proponents of different religions, but among conflicting groups inside those religions as well. In some instances, contemporary religionists don’t run each other off; they shoot each other down.

Yet events at Antioch of Pisidia, now an archeological dig in modern Turkey, represent a biblical foretaste of socio-religious discord that endures to this day. Such conflicts rage across our world, not just between proponents of different religions, but among conflicting groups inside those religions as well. In some instances, contemporary religionists don’t run each other off; they shoot each other down.

Today, religiously underwritten “violent resentment” seems both national and global: Jews and Arabs in the Middle East, Eastern Orthodox Christians in Russia and Ukraine, and Protestant against Protestant in the United States.

A Jan. 7 article in the New Yorker Daily quotes Iowa Republican legislator and evangelical minister Jon Dunwell on the “vein of Christian nationalism” in his party, persons he says believe “that Christianity should be the supreme religion of the United States, and everything should be judged in subjection to that.”

Dunwell adds, “They say my (Boomer) generation of Christianity is the reason America is this way, not because we were ineffective in transforming lives but because we weren’t bold enough to grab the sinner by the neck and throw him down and enforce the laws of God. And that, to me, is scary. It’s a little bit — it can be Talibanistic.”

Baptist News Global quotes a Republican political operative and Baptist seminary graduate who says, “If you can’t admit that Beth Moore was an ungodly, even demonic, influence on the SBC — I really won’t be able to trust you.” Demonic because she says women can, should, do preach the gospel? If that’s not 21st century Christianity-based “violent resentment,” then nothing is. Challenge her biblical interpretation if you must but forsake the title “demonic,” applied to a Christian sister.

The Acts text recounts one of the most radical events in Christian history, when Gentiles were “grafted on” to a redemption traced from “Moses and the prophets” to a first century rabbi from Nazareth. So, the Gentiles (that’s us) were invited into God’s grace, in part because Paul and Barnabas got run off by the Jews in Antioch.

We Christians paid them back for that, with two millennia blaming Jews for rejecting the Word made flesh. The list of anti-Semitic atrocities and pogroms runs like a trail of tears across Catholic and Protestant history. Remember when their Catholic majesties Ferdinand and Isabella forced the inconversos, “unconverted” Jews, out of Spain in 1492, the same year that “Columbus sailed the ocean blue”?

The documents of Vatican Council II … noted “the Jews should not be presented as rejected or accursed by God, as if this followed from the Holy Scripture.” Finally!

Not until 1965 in the documents of Vatican Council II did the church declare Christ’s death “cannot be charged against all the Jews, without distinction, then alive, nor against the Jews today.” The document noted “the Jews should not be presented as rejected or accursed by God, as if this followed from the Holy Scripture.” Finally!

Our Protestant forebears were not far behind. Martin Luther, his conscience somewhat less than “captive to the Word of God,” authored a 1543 diatribe titled “The Jews and their Lies,” declaring: “What shall we Christians do with this rejected and condemned people, the Jews? Since they live among us, we dare not tolerate their conduct now that we are aware of their lying and reviling and blaspheming.”

Luther advised Christians to burn Jewish synagogues, homes and holy books, and “let them live in barns, like Gypsies,” Had we listened to him on this subject, we could be singing: “A Mighty Fortress is our God, a Bigot never failing.”

Christians visited “violent abuse” on the Jews. Then we turned on each other. Medieval Catholics burned the Moravian patriarch John Hus at the stake in 1415; colonial Puritans hanged Quaker Mary Dyer in Boston in 1660; 18th century Virginia Anglicans jailed Baptist Elijah Craig for preaching without a state license. They ran him off to Kentucky, where he invented Bourbon whisky, but that’s another story.

Today, who can keep track of the Christians, Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, Jews et.al. killed or harassed in religion-related worldwide conflicts?

Identity and ideology can inspire and inflame, sometimes simultaneously. Choosing one religious identity can bring us compassion or set us at odds with those of other faith traditions. Identity is a powerful resource for knowing who we are and where we fit in the world and in relationship with God.

Then comes the dilemma. Does our religious identity exclude or invite, alienate or engage? Is it inevitable that ideas create division, even conflict, because they are powerful, energizing and disruptive? For religion to be “true,” must it dominate a culture? Can we cling tenaciously to conscience-laden convictions without succumbing to the language or actions of violence?

In January 2024, we can remember Martin Luther King Jr. and his commitment to nonviolence amid differing identities and ideologies. In a 1959 sermon, King declared: “The aftermath of nonviolence is the creation of the beloved community, so that when the battle’s over, a new relationship comes into being between the oppressed and the oppressor. … The way of acquiescence leads to moral and spiritual suicide. The way of violence leads to bitterness in the survivors and brutality in the destroyers. But the way of nonviolence leads to redemption and the creation of the beloved community.”

A nameless Canaanite woman taught Jesus a thing or two about beloved community when, Matthew 15 says, she started shouting, “‘Have mercy on me, Lord, Son of David; my daughter is tormented by a demon.’ But he did not answer her at all. And his disciples came and urged him, saying, ‘Send her away, for she keeps shouting after us.’”

She was a Gentile, so Jesus responds, “‘I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel.’ But she came and knelt before him, saying, ‘Lord, help me.’ He answered, ‘It is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to the dogs.’ She said, ‘Yes, Lord, yet even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their masters table.’”

And Jesus finally gets it. “Woman,” he says, “great is your faith! Let it be done for you as you wish.” Matthew says, “And her daughter was healed from that moment.” The light to the Gentiles began with Jesus and the nameless Canaanite woman, long before Paul and Barnabas got run out of Antioch.

Jesus’ Jewish voice sings out across the centuries: “I give you a new commandment: Love one another as I have loved you,” a compassionate identity so all-encompassing that ultimately no one should eat only the crumbs from anybody’s gospel table. Hope, 2024.

Bill Leonard is founding dean and the James and Marilyn Dunn professor of Baptist studies and church history emeritus at Wake Forest University School of Divinity in Winston-Salem, N.C. He is the author or editor of 25 books. A native Texan, he lives in Winston-Salem with his wife, Candyce, and their daughter, Stephanie.

Related articles:

American democracy is in danger, and so is the gospel

Bonhoeffer moment No. 1: Claiming Christ but losing the gospel

Are our churches prepared for Christian autocracy?