The Lost Cause myth is the original Big Lie, building on cultural, historical and religious elements of culture to try to create (or recreate) a world where white men reign supreme and some version of America is Great Again. One of the most important historians of the Lost Cause is Ty Seidule, who chaired the history department at West Point and was deeply steeped in the mythologies before he saw the light. He talked about his personal journey of recognition — and about American history and culture — in his book Robert E. Lee and Me, and he continues to talk about white Christian nationalism, the Lost Cause and how we need to recognize and tell the truth today about race, religion and white supremacy. I’m grateful to Gen. Seidule for his time and expertise and hope you’ll find this conversation enlightening.

Greg Garrett: Two years ago, just after the first anniversary of January 6, you and I talked about your book Robert E. Lee and Me and about the Lost Cause myth. On that occasion, we both mentioned being haunted by the image of that rioter walking through the halls of the Capitol carrying a Confederate battle flag, and you told me, “It means the same thing now that it meant then,” that the battle flag continues to be a marker of white supremacy in our present. In the interlude since we’ve talked, politicians and media figures have argued it doesn’t mean the same thing, that the January 6 riot wasn’t what we all witnessed. You’re a historian, and a good one. Could you talk about how we can use history to help make sense of our present? What does it mean to live at a moment when some people don’t want our whole history acknowledged or even properly taught?

“What does it mean to live at a moment when some people don’t want our whole history acknowledged or even properly taught?”

Ty Seidule: History is dangerous because it challenges our myths and even our identity. Today, we see people trying to change the meaning of an event to fit their politics and their worldview. As historians, we must tell the story of what happened in clear language backed by facts.

There are facts. A mob, incited by President Donald Trump, broke into the People’s House to stop the peaceful transfer of power. Today, those violent insurrectionists are being held to account for their actions by juries of their peers. The rule of law is working. We must use clear language to describe what happened and why.

Ty Seidule

Here’s another fact: A now convicted felon brought the Confederate flag — the flag of treason, a flag that nearly destroyed our country, the flag of slavery — into the People’s House. That flag represented many white Southerners who would not accept the result of a democratic election and chose armed rebellion instead. That’s what the flag meant in 1861. It means the same thing today.

Unless we understand history, we can’t understand ourselves. We can’t understand this moment. Everything has a history. Moreover, how can we ever hope to know where to go, if we don’t know where we’ve been?

So many folks want to prevent schools from teaching accurate, meaningful history as many did a hundred years ago. The United Daughters of the Confederacy published A Measuring Rod to Test Textbooks to ensure school boards forced children to learn Lost Cause lies in the early 20th century. My Virginia history textbooks from the 1960s and 1970s still taught children that slavery was the best system for its time and segregation worked. Compared to that, textbooks are much better now. Plus, the internet has provided a wealth of sources unavailable just 20 years ago. Look at John Green’s Crash Courses, Clint Smith’s Black American History Crash Course, or my own video, Was the Civil War about Slavery? No politician can hide the truth anymore.

GG: In Robert E. Lee and Me, you describe bringing your wife, Shari, and your teenage sons into the Lee Chapel at your alma mater, Washington and Lee. When she walked inside, she had a visceral reaction to seeing Lee’s statue atop the table where the altar should be in a house of worship. Seeing the scene through her eyes seems to have been an important step in your process of confronting the world in which you (and I) had been immersed. Could you say a bit about some of the ways the Lost Cause myth was embedded in your life as a Southern man, a soldier, maybe even as a person brought up — like Lee — an Episcopalian? How has the Lost Cause myth misshaped its adherents and our nation? What might help other Americans have that moment of recognition that Shari seems to have been part of for you?

TS: How was the Lost Cause embedded in my life? How does a fish know it’s wet? It infused my life in all respects. I wanted to be an educated, Christian, Virginia gentleman. Those titles represented status and power. Lee was a good Episcopalian, another marker of status. My first chapter book was Meet Robert E. Lee, which told me Lee was one of the greatest Americans ever. Gone with the Wind, my first adult book, showed me that Antebellum plantations represented the best possible life. Lies. Plantations were gulags, sites of mass atrocities.

“The Lost Cause made evil positive and equality suspect.”

The Lost Cause infected our nation with several lies. First, that the white South didn’t go to war to protect and expand slavery. It did. Second, that slavery was not that bad. More lies. Slavery was an abomination. Third, that African Americans weren’t ready for self-rule and democracy. Yet, 2,000 Black men held elected office from 1865 to 1877. The Lost Cause made evil positive and equality suspect. The Lost Cause became the ideological foundation of a racial police state, the Jim Crow society. To enforce third-class citizenship on African Americans, the white South launched a terror campaign of lynching to enforce white supremacy.

My wife, Shari’s, honesty changed my life. She allowed me to see the truth through the lies of my culture. What might help others? The writer Gore Vidal wrote that the person who screens the history, makes the history. Try watching 12 Years a Slave, Underground Railroad, Stamped from the Beginning, Emancipation, 13th, and Harriet. These movies provide a more realistic look at the moral horror of slavery and the role African Americans had in ending it.

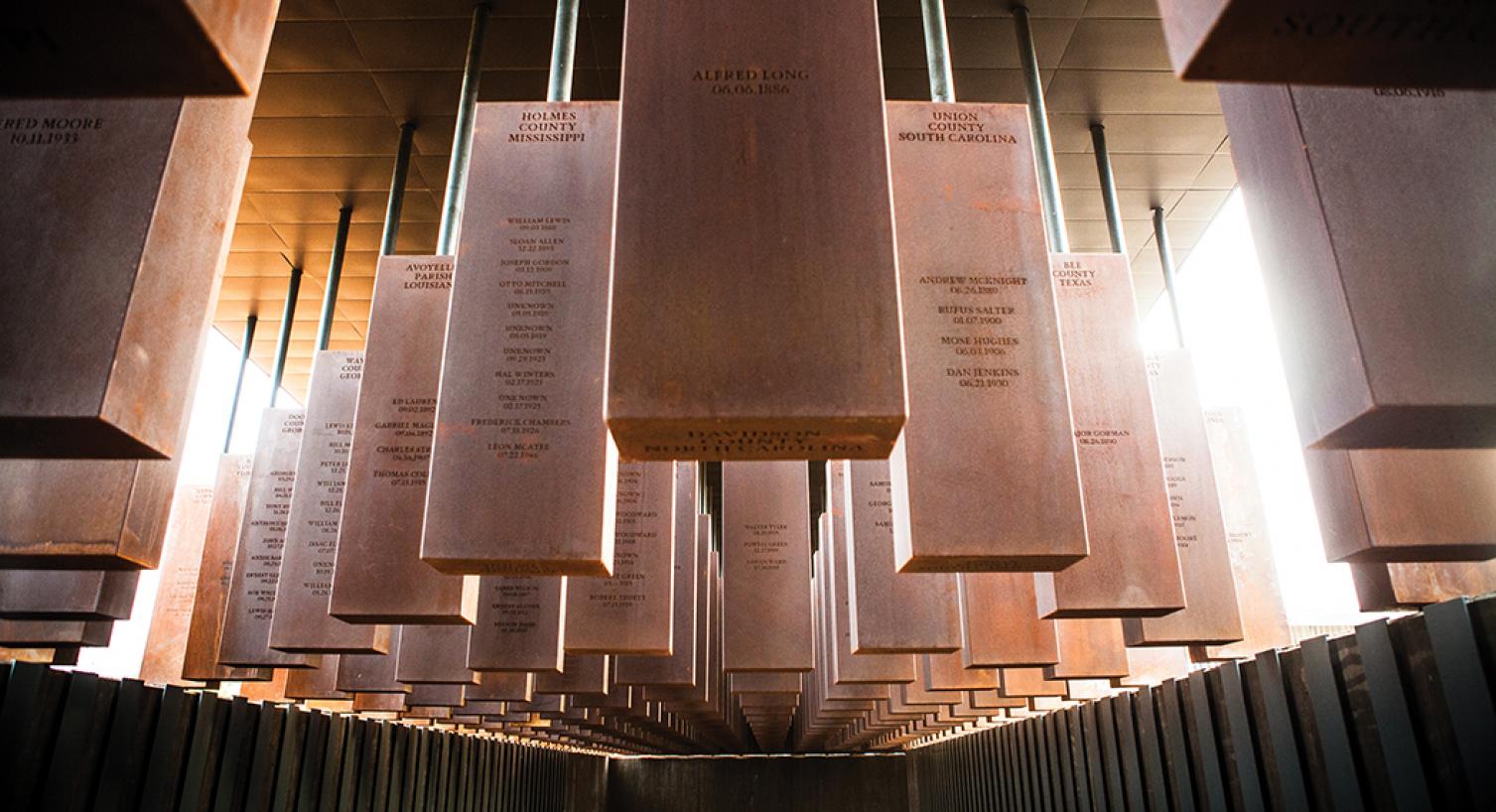

I also recommend folks go to the incredible new museums that have opened in the last 10 years. The National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, the International African American History Museum in Charleston, the Legacy Museum in Montgomery, the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum in Jackson, the Whitney Plantation Museum in Louisiana. I’ve visited all of them. They tell a powerful, moving, emotional and accurate story.

Lynching memorial

GG: You recently told a Congressional committee that the military pursues diversity because diversity works: “Diversity is the military’s strength because diversity is America’s strength.” This was not necessarily what the committee wanted to hear; you were invited to address a hearing on “The Risks of Progressive Ideologies in the U.S. Military.” It is, as you’ve noted this spring, ironic that the party of Lincoln now seems to be so resistant to truths about race and equity. How did we get here? What explains this hysteria on the far right about DEI initiatives and Critical Race Theory? How can we make the point that diversity is indeed America’s strength?

“Every time there is a moment toward equal rights, there is a counter movement to protest or squash those rights.”

TS: Every time there is a moment toward equal rights, there is a counter movement to protest or squash those rights. The end of slavery begat the Klan. Reconstruction (1865-1877) begat Jim Crow. The Civil Rights Movement begat George Wallace and racist populism. Barack Obama’s election begat the Tea Party. The summer of George Floyd’s murder and Black Lives Matter protests begat the war on CRT and DEI.

CRT argues that some of America’s laws were written with racist intent. Hard to argue against that.

Diversity is America’s strength. Our superpower is bringing immigrants in from all over the world and making them Americans. Yet, that policy is only about 60 years old. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 ended a racist law that prevented immigration from Africa and Asia. Over the last 60 years, America has opened its doors to “those who can contribute most to this country — to its growth, to its strength, to its spirit.”

Immigrants founded and run some of America’s greatest companies. Immigration is the reason our economy has done better than Europe’s over the last five years.

When people ask me to prove that diversity works, I point to the U.S. military. We have the greatest military in the world because we represent and reflect the greatest nation in the world. The U.S. military has implemented diversity practices for the last 50 years. Why? Because focusing on the strength of diversity works. We also have the most diverse workforce in the country. The Army alone brings in 10,000 new people a month. We must ensure all soldiers understand our values, and that requires training and education.

GG: I wanted to bring together a number of diverse voices this election year to talk about where we are as Americans and as people of faith or people shaped by faith. White Christian nationalism alarms me, as it does many of the liberal and conservative Christians with whom I’ve spoken. How should we understand the appeal of Christian nationalism? Does it concern you? As a historian — or simply as a human — what are the things that worry you most about our present American moment?

TS: We have always had groups in America that find their power in keeping other people out of power. Oppression under the guise of religion is an American tradition.

“Oppression under the guise of religion is an American tradition.”

We must, however, stop equating white evangelicals with all Christians. Black Christians, Korean American Christians, Mainline Protestant Christians and many others practice Christian traditions and deserve more study. White Christian nationalism seems less about Christianity and more about white nationalism. Perhaps, we should stop talking about them as Christians until they start acting like Christians. Until then, lets focus on those groups that do try to follow the gospel.

GG: Not long ago, the Confederate memorial at Arlington Cemetery — which you told me was “the cruelest monument in the country,” came down. The statue of Lee in Richmond has been melted down and will be turned into new public art. The windows commemorating Lee and Stonewall Jackson in Washington National Cathedral have been replaced by stained glass created by the African American artist Kerry James Marshall. As hard as these past years have been, as much rollback as there has been in some quarters on race and justice, we’ve also seen these signs that a more inclusive future is possible. Where are you finding hope? What thoughts do you have about how we might continue our quest for a more perfect union?

TS: I do find hope. I finished writing my book, Robert E. Lee and Me, in late 2019. It came out in January 2021. The book is, in some ways, a polemic against the ubiquity of Confederate commemoration, racist commemoration, in the military and in the nation. Since publication, more than 90% of the names, monuments and memorials have been removed or changed. Amazing! 1,111 Confederate names in the Department of Defense are gone. West Point now has no Confederate commemoration.

Why? Because Congress passed a law and then overrode President Donald Trump’s veto to create the Naming Commission I served on. The American people, through their elected representatives made it happen. When we went to change the army post names, we found very little resistance. The new names inspire all of us. Hal and Julie Moore, Van Barfoot, Charity Adams, Arthur Gregg, Henry Johnson, Mary Walker, and Richard Cavazos are true American heroes who fought for this country we love. The U.S. military no longer honors those who chose treason to preserve slavery. Most Americans, I believe, know that Confederates no longer represent our values. And we have so many other heroes that deserve recognition.

I am a proud American. I believe we will make our nation a better place for our children and grandchildren, but that only happens when good people fight for equality.

We’ve come a long way, and we have a long way to go.

Greg Garrett teaches creative writing, film, literature and theology classes at Baylor University. He is the author of two dozen books of fiction, nonfiction, memoir and translation, including the critically acclaimed novels Free Bird, Cycling, Shame and The Prodigal. His latest novel is Bastille Day. He is one of America’s leading voices on religion and culture. Two of his recent nonfiction books are In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett and A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. He is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

Related articles in this series:

Politics, faith and mission: A BNG interview series on the 2024 election and the Church

Politics, faith and mission: A talk with Tim Alberta on his book and faith journey

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jemar Tisby

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Leonard Hamlin Sr.