I was fussing over a jigsaw puzzle when somebody turned on the Biden-Trump debate. As the combatants droned on in the background, my attention remained firmly fixed on the task before me. It was all birds and foliage. A thousand pieces. There was no way I would get it done before my week at Chautauqua was done, but I soldiered on.

Chautauqua is an ecumenical, interfaith institution founded in 1874 as a training center for Sunday school teachers. Most of the buildings in the 750-acre grounds were built in the late 19th century or are built to appear as if they were.

Six members of my Fort Worth Sunday school class made the journey to northwest New York State to spend a week listening to lectures, concerts, dramatic productions and a variety of religious services. We shared a cottage built in 1879 with six other Chautauquans. Watching the Trump-Biden debate hadn’t been on the menu, but the television was located three feet from my puzzle table, so I had no choice but to listen.

Nothing had prepared me for the worst debate in American history.

Nothing had prepared me for the worst debate in American history. Trump spewed a steady stream of lies. He spouted random clips from his campaign rallies that were radically unrelated to the questions he had been asked. It was a disgraceful display.

But Biden couldn’t rise to the occasion. He paused awkwardly in mid-sentence. He was agitated by Trump’s misrepresentations, but he couldn’t tell us why.

I didn’t realize how bad Biden’s performance had been until Anderson Cooper asked John King for his impressions. “Anderson, this was a game-changing debate in the sense that, right now as we speak, there is a deep, a wide and a very aggressive panic within the Democratic Party,” the CNN analyst replied. “They’re having conversations about what they should do about it. Some of those conversations include: Should we go to the White House and ask the president to step aside?”

David French speaks at Chautauqua.

The following day, when David French rose to speak in Chautauqua’s immense outdoor amphitheater, Biden was on everyone’s mind. French was clearly open to the idea of the president throwing in the towel, but he reminded the audience that it was Biden’s call.

A week later, as a guest on the Never-Trump Bulwark podcast, French shared he had watched the debate in the company of several dozen Chautauqua organizers. “These were Biden’s people, and they were gob-smacked,” he said. “I thought we might be witnessing some kind of medical event.”

A centrist institution

Biden is a centrist. That’s why he is popular at Chautauqua. From its beginning in 1874, the Chautauqua Institution has appealed to white Mainline Protestants. The “Seven Sisters” of the American Protestant Mainline are the United Methodists, the Episcopal Church, the United Church of Christ, The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, The Presbyterian Church (USA), the Disciples of Christ and the American Baptist Churches (USA). A few smaller denominations sometimes are described as “Mainline,” including the group my congregation calls home, the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship.

In recent years, the Chautauqua Institution has welcomed Catholics and Jews and officially is “interfaith.” Although Chautauqua still is overwhelmingly Protestant, Catholics now comprise the largest single denomination represented on the grounds. In recent years, the door has opened to Muslims, Buddhists, agnostics, atheists and anyone else who shows up for a day, a week or the entire nine-week summer season. That said, most of the people who flock to Chautauqua every summer are white Mainline Protestants.

Conflicted congregations

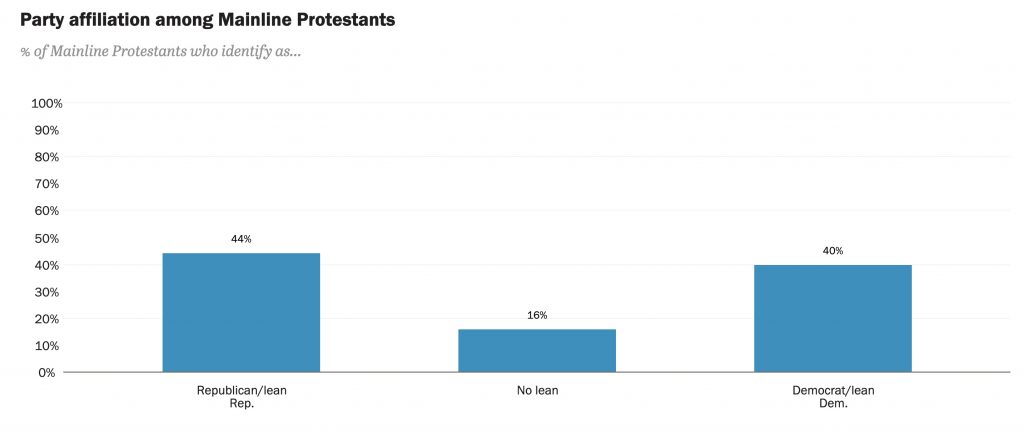

White Mainline Protestants often are described as religious liberals. This is a serious misunderstanding. A recent Pew study revealed Mainline Protestants are more likely to vote Republican (44%) than Democratic (40%). Only 20% of white Mainline Protestants describe themselves as liberal, while 38% self-identify as moderate and 37% as conservative. That’s about as centrist as you can get!

Table via Pew Research

Not surprisingly, the Protestant Mainline also is theologically diverse. While 80% believe in heaven, 20% either don’t believe or don’t know. Only 60% believe in hell.

Mainline Protestants aren’t sure what to do with the Bible. According to the Pew study, 24% believe the Bible is God’s word and should be interpreted literally, 35% say the Bible is the word of God but shouldn’t be interpreted literally and fully 28% don’t believe the Bible is the word of God in any meaningful sense. Not surprisingly, 44% read the Bible seldom or not at all.

Mainline Protestants are similarly divided on social issues. Sixty percent say abortion should be legal in most cases, but 35% believe it should be illegal in most cases. Two-thirds believe “homosexuality” should be accepted, while 26% believe it should be “discouraged.”

A third of Mainline Protestants say human evolution is a natural process with no divine involvement; a third believe God guided the process; and a third don’t believe in human evolution at all.

A third of Mainline Protestants say human evolution is a natural process with no divine involvement; a third believe God guided the process; and a third don’t believe in human evolution at all.

Responses skew a bit in a liberal direction among the better-educated members of the group, but not dramatically. Opinions also vary by denomination, with Episcopalians and members of the United Church of Christ reflecting the most liberal views on most subjects, and United Methodists and American Baptists holding down the conservative end of the Mainline spectrum. Predictably, urban Mainline congregations tend to be more liberal than their rural and small-town counterparts.

To the surprise of no one, a recent Public Religion Research Institute survey revealed Mainline pastors are considerably more liberal than their congregants. For instance, 90% of Mainline clergy support “laws that would protect gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people against discrimination in jobs, public accommodations and housing,” compared to 77% of church members.

Chautauqua mirrors the Mainline

About 5,000 people on hand for the first week of the summer program were clearly more affluent than the average Mainline Protestant; a week at Chautauqua sets you back several thousand dollars. Although I can offer no documentation, Chautauquans appear to me, at least, to be far better educated, much older and considerably more introverted than the general population. These are people, after all, who sacrifice financially to take in dozens of lectures.

Chautauqua has its own symphony orchestra, which performs twice a week during the summer, and a resident opera company. Attendance at these “high culture” events was typically modest, however. Martina McBride and the Beach Boys, with a single original member, drew a much bigger crowd.

Each day begins with a worship service attended by about 1,000 people scattered throughout an amphitheater designed for four times that number. The worship style is strictly old-school — a robed choir, organ accompaniment, traditional liturgy and a 20-minute sermon.

The gospel according to Greg Boyle

The preacher for our week was Gregory Boyle, the founder of Homeboy Industries in Los Angeles. A Jesuit priest, Boyle works almost exclusively with gang members and ex-gang members. His brief homilies consisted primarily of poignant anecdotes culled from decades of work with the most vulnerable population in Los Angeles.

Greg Boyle (Photo/Wikipedia)

Boyle believes in unconditional love and radical forgiveness.

“The goal of all this is not to save your soul, but to spend it,” he said. “We don’t get saved from ourselves, but to ourselves. … More often than not, it is your broken heart that opens your loving heart. … God protects us from nothing but sustains us in everything.”

Boyle eschews theological dualism. His God loves and forgives everyone, without qualification. We can’t earn God’s approval, and we don’t have to, he says. God sees the beauty inside us, even when we are blind to it. Transformation happens when we see what God sees. Although Boyle loves his Jesuit tradition, he sees it as just one of many paths to God. His theology is perfectly suited to an interfaith context.

Straddling the ideological divide

Chautauqua has been ecumenical and theologically progressive from its earliest days. John Heyl Vincent, one of Chautauqua’s founders, believed “nothing is secular in any sense as to make it foreign or unattractive to the saints of God.”

My impression was that most Chautauquans, as they call themselves, are socially liberal and politically centrist. At any rate, speakers are intentionally drawn from both sides of America’s ideological divide, from center-right to center-left. Hyper-partisan voices are avoided. Historian Jon Meacham, Monday’s keynote speaker, is an informal adviser to Joe Biden, but he also enjoyed access to both Bush administrations.

David French, Friday’s headline speaker, is a Never-Trump Republican who has spent much of his professional life defending conservative Christians in civil cases. Having been recently drummed out of his conservative denomination, the Presbyterian Church in America, French understands the religious dimension of the MAGA movement all too well.

After an address by Andrew Card, chief of staff in the George W. Bush administration, I joined a talk-back session with several dozen earnest Chautauquans. I expressed my amazement that a man who presided over one of the worst foreign policy debacles in American history could speak for an hour without issuing either an apology or a defense. This comment was not graciously received. The folks who dominated the discussion were looking for political middle ground and glimmers of reconciliation. One woman suggested we should talk more about tax policy because everybody wants to keep taxes as low as possible.

The Mainline resembles Joe Biden

Compared to white evangelicals, the Protestant Mainline doesn’t get a lot of press. This may be because 81% of white evangelicals vote for Donald Trump, while the Mainline divides its vote equally between the two major parties. Since the 1970s, Mainline churches have been shrinking at an alarming rate, while evangelical churches have exploded. In the last decade, the pace of Mainline decline has slowed somewhat, while attendance at evangelical churches has dipped sharply.

Who wants to book passage on a sinking ship?

Since I attend a Baptist church that has embraced the Mainline label, this demographic decline concerns me. Who wants to book passage on a sinking ship?

Worship at Shoreline City Church.

Would Mainlines churches grow if we jettisoned our liberal preachers, mothballed our pipe organs and adopted a Hillsong musical repertoire? Not likely. Mainline churches are in an advanced state of decline because they are internally conflicted. Our clergy shy away from simple declarative sentences for fear of upsetting a fragile equilibrium. In many churches, the slightest hint of political favoritism can spark a controversy. In a nation where every subject is fraught with culture-war implications, even self-help sermons can be misconstrued as political. Mother’s Day is a minefield.

As the Pew study indicates, many Mainline congregations are just as conflicted theologically as we are politically. We don’t know what to do with the Bible. We are unsure about the nature and character of God. We struggle to define traditional words like “salvation.”

Theological disagreement, per se, is inevitable. It can even be healthy. But if our differences make it impossible to address the kind of questions our young people are asking, we’ve got a problem. The primary reason young people leave our churches is because they no longer believe the message. When pastors avoid hard questions for fear of backlash, they lose their most thoughtful young people.

If we make our religion apolitical, what is left to talk about? Our hymnody becomes as banal and muffled as our sermons. No wonder our children sleep in on Sunday mornings as soon as they leave for college — if we are fortunate to hold them that long.

Our churches look and sound a lot like Joe Biden — earnest, well-intentioned and hopelessly tongue-tied.

How we got here

I was a pastor 20 years, so I know there are no easy answers. Ryan Burge, a highly regarded sociologist and American Baptist pastor, presided over his congregation’s final worship service. Burge loved his people, and they loved him. I doubt any pastor in America could have saved Burge’s congregation. A PRRI study indicates 35% of Mainline pastors lead congregations with fewer than 100 members. That may be why over half of Mainline pastors have seriously considered leaving the ministry.

Before we can turn things around, we’ve got to understand how we got here. That will be my focus in future columns.

Alan Bean

Alan Bean serves as executive director of Friends of Justice. He is a member of Broadway Baptist Church in Fort Worth, Texas.

Related articles:

New book shows how Mainline churches promoted Christian nationalism by another name

‘Operation Reconquista’ aims to return Mainline churches to ‘orthodoxy’

Making sense of denominational decline and church shifting

In biblical truth-telling, we need to mind the gap between clergy and laity