Regular attendance at church — almost any church, even the liberal ones — makes people more conservative, Ryan Burge, an analyst of religion and politics, reported.

In a recent post on his Substack column, “Graphs About Religion,” Burge demonstrated the connection between various levels of church attendance and the spectrum of conservative-to-liberal beliefs.

“There is almost no ‘liberalizing religion’ in the United States,” he said. “The more people attend, the less liberal they are.”

Burge is an assistant professor at Eastern Illinois University who is well-known for his research on U.S. religion. He particularly has been cited for documenting the rise of the “nones,” people who indicate “none” when asked about their religious affiliation.

Ryan Burge

He cited research conducted by Landon Schnabel, an assistant professor of sociology at Cornell University.

“The conceit (of Schnabel’s study) is pretty simple — there are lots of examples of highly religious people being really conservative,” Burge explained. But “Schnabel wants to conduct a search for any evidence that being highly engaged in a certain religion pushes someone to the left side of the political spectrum.”

Schnabel found precious little of such evidence, Burge said, quoting from the last paragraph of Schnabel’s report: “Even ‘liberal’ religion is typically conservatizing ….”

Previous research pointed toward such a conclusion, Burge acknowledged, citing data from a couple of years ago that focused on “measuring beliefs about the social gospel.”

That research compared belief that “God is more concerned about individual morality than social inequalities” to church attendance among Republicans, Democrats and Independents.

“In other words, the more Democrats go to church, the more they look like Republicans.”

“It’s no shocker that Republicans are less likely to subscribe to the tenets of the social gospel” than Democrats and Independents, he said. But the data showed the more frequently members of all three groups attend church, the more they tend to emphasize individual morality over social inequalities.

“In other words, the more Democrats go to church, the more they look like Republicans,” he wrote.

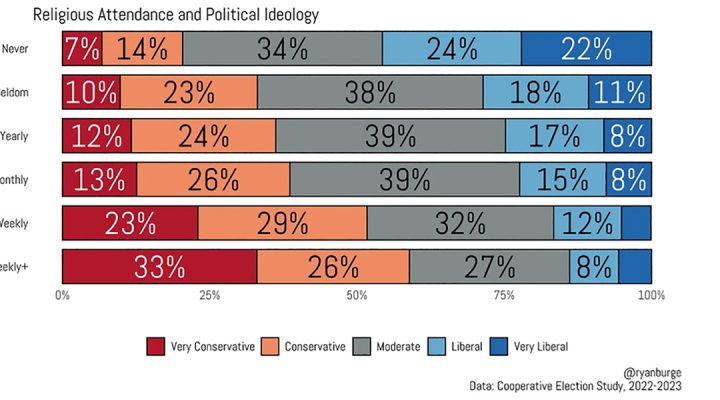

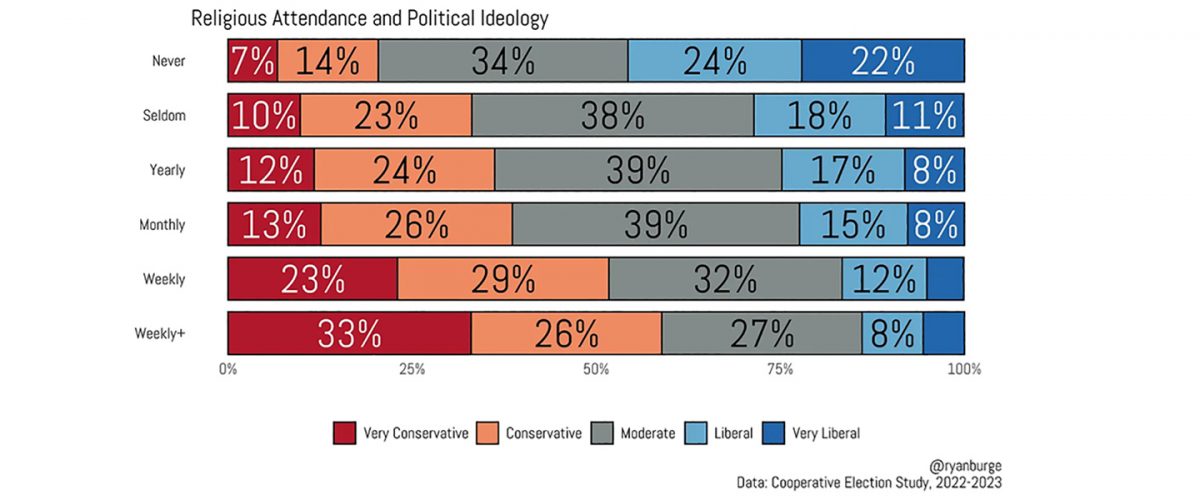

Next, Burge examined the specific connection between church attendance and political ideology. He compared how often people go to church with how they self-identify on the conservative-liberal political spectrum.

This data showed expected results. Among people who said they never attend church, 21% called themselves conservative or very conservative, while 46% called themselves liberal or very liberal.

Meanwhile, among respondents who attend church more often than weekly, 59% identified as conservative or very conservative, while 14% said they are liberal or very liberal. Among weekly attenders, 49% said they are some level of conservative, and 16% said they are some level of liberal.

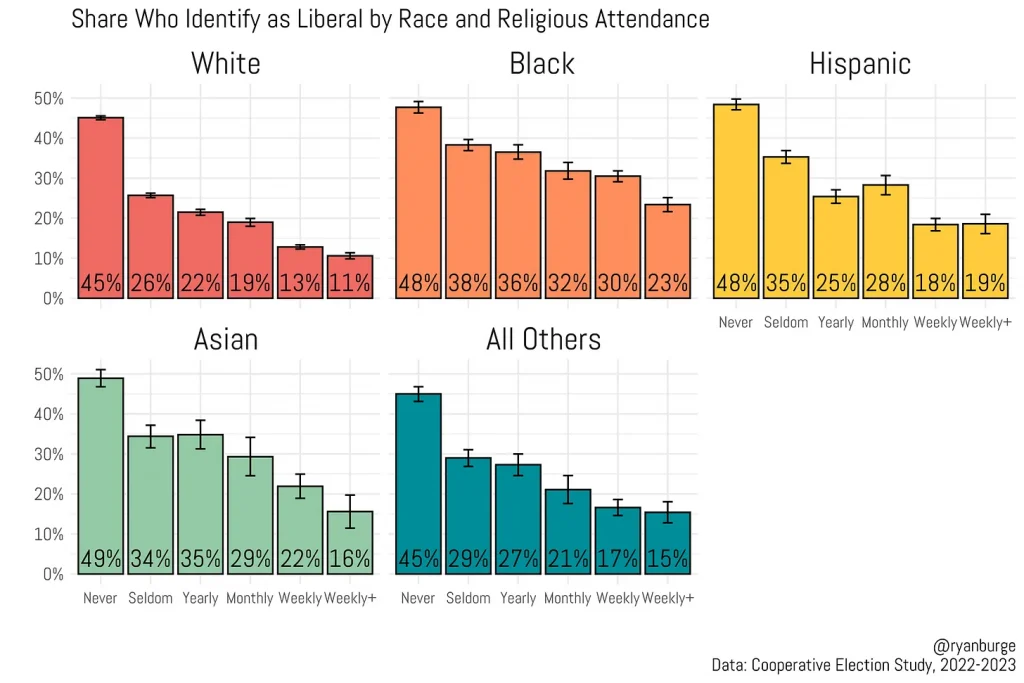

Turning to race, Burge reported the pattern still holds.

“Among white respondents, 45% of never attenders are liberals. It’s just about 12% of white weekly attenders,” he said. “A Black person who never attends religious services is twice as likely to identify as a liberal, compared to one who attends multiple times per week — 48% vs. 23%.”

For Hispanics, “the trajectory is the same,” he added. “There aren’t many Hispanic liberals in the pews each Sunday.

“People who are more religiously active are significantly less likely to describe themselves as liberals.”

“There’s just no two ways about it. People who are more religiously active are significantly less likely to describe themselves as liberals. That’s the case for every racial group as well.”

The trend line also holds for attendance by adherents of Protestant faith groups.

Among 20 U.S. Protestant denominations or nondenominational affiliations, 18 show a direct correlation between frequency of church attendance and conservatism, Burge noted.

“Those who attend most frequently are the least likely to identify as liberal,” he said. “That’s true for Southern Baptists and a lot of nondenominational folks, too. Which tracks — those are evangelical denominations.”

For example, among Southern Baptists, well less than 10% of weekly-plus attenders identify as liberal, compared to about 30% of never attenders. Among “other nondenominational,” the trend line is similar — about 10% of weekly-plus attenders and less than 30% of never attenders are liberal.

But similar trends also hold for the so-called liberal denominations, Burge observed.

“What may be most striking is that even folks who are members of what are perceived to be left-leaning or moderate denominations like the United Methodist Church and the Presbyterian Church (USA) are showing a similar pattern to Southern Baptists — higher attendance means less liberalism,” he said.

Slightly more than 40% of never-attending United Methodists identify as liberal, compared to less than 20% who go to church more than weekly. In the Presbyterian Church (USA), not quite 40% of never-attenders identify as liberal, and slightly more than 5% of weekly-plus members claim the liberal tag.

The only two denominations that reverse the trend are the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and the Episcopal Church, Burge said.

“That’s the only two out of these 20 where the most frequent church goers are more liberal than those who attend with less frequency,” he said. “Those two denominations represent about 8% of the sample. … The Southern Baptists by themselves are 15%.”

Catholics follow a similar pattern, except the weekly-plus attenders are slightly more liberal than the weekly attenders. Among never-attenders, 28% are liberal. For weekly attenders, the number is 18%, and for weekly-plus, it’s 22%.

“It’s hard to look at this data and say that there are significant pockets of liberalizing religion in the United States,” Burge noted. “The more people go to church, the less liberal they are. That’s true across all racial lines. That’s also true in a lot of major Protestant traditions.”

Sometimes, mainline church leaders “ask me if it would be wise for them to spend time and resources on publicizing the fact that their church is not conservative,” he reported. “I don’t know if there’s an empirically driven answer to that question. …

“For anyone born in the last 40 years or so, the only conception they have of religious activism is likely tied up with the Religious Right, which, of course, was a conservative movement.

“Maybe the idea that religion can push people toward left-leaning ideas is over for good. It’s hard to say. Or maybe the pendulum will swing back. … From this data-driven vantage point, there’s plenty of evidence that American religion is now inextricably linked to one political viewpoint. For good or ill.”

Related articles:

Ryan Burge explains ‘casual dechurching’

In BNG webinar, Ryan Burge details the double threat to denominational churches in America

Ryan Burge sifts the data to paint an evolving portrait of the ‘nones’