Political party leaders around the globe, including Donald Trump, are openly flirting with fascism to consolidate power by exploiting economic and cultural conflicts. When considering how to respond to these troubling developments, many Christians rightly turn to the example of Lutheran pastor and theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

He spoke out against the Nazi party and was executed for his connection to an assassination plot against Adolf Hitler. Yet few Baptists know we have our own role model in German Baptist pastor Arnold Köster. Köster’s ministerial platform was not nearly as lofty as Bonhoeffer’s, but his example is no less important because his is someone church leaders and congregations can more readily emulate.

Life story

Arnold Köster was born in 1896 in the small German village of Wiedenest, where his father served as a Baptist minister. While still a teenager, Köster decided to enter the ministry, a call that only deepened after his experience as a soldier in World War I. After the war, Köster attended seminary in Hamburg-Horn, Germany.

He spoke publicly at the Baptist Union of Germany saying that a “terrible illusion is spreading all over Germany, threatening to gag the hearts and minds of everyone.” The Nazi Party’s “Germany First” agenda appealed to those suffering under the crushing reparations demanded in the Treaty of Versailles. During his three years in seminary, Köster saw the party’s numbers swell from 2,000 members to 20,000.

In 1929, after serving as pastor of two German churches, Köster left his homeland to lead a prominent Baptist congregation in Vienna, Austria, at Wien-Mollardgasse 35. His new position did not dampen his outspoken distrust of the Nazi party.

“Widespread propaganda was deluding Christians into thinking Hitler was sent from God.”

Paul Spanring, pastor of Cheddar Baptist Church in England and author of the book Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Arnold Köster: Two Distinct Voices in the Midst of Germany’s Third Reich Turmoil, says Köster warned his congregation against zeal for the Nazis. Widespread propaganda was deluding Christians into thinking Hitler was sent from God. He believed the party’s promise of “salvation” (Heil in German) was competing with the saving message of the gospel. He made clear that for the Christian, Christ alone was the “ultimate leader” (Führer).

Köster was co-editor of the Täufer-Bote (Baptist Messenger ), a German-language magazine printed in Vienna for Baptist congregations in the countries around the Danube River. His column from January 1932 emphasized the pressing need for prophetic watchmen like the one in Ezekiel 33, who would sound the alarm over the dangers of fascism.

Describing the Nazis, Köster said: “They stormed past with a defiant spirit and incredible impudence while the mass of the people, drunk and hypnotised, hoped that ‘this day’ would bring salvation. Heil! Heil! — and still there is no Heil! Even the church — in still greater blindness — walks past the question of God while its representatives are dressed in holy and pious garb.”

He believed it was the duty of God’s churches to act as God’s prophets during that “dark and mysterious” time.

He believed it was the duty of God’s churches to act as God’s prophets during that “dark and mysterious” time.

Call not heeded

Sadly, most Baptist churches did not heed Köster’s call. Spanring says, “At that time many Baptists were either swept along by the Nazi enthusiasm or argued for an apolitical stance.” In his book, Spanring, who is himself Austrian, translates Köster’s description of a meeting he had with the Baptist Union of Germany in 1933:

They thoroughly grilled me for several hours; “What is your argument with National Socialism? Why don’t you keep your mouth shut? After all, you endanger the whole Baptist movement …” When I drew their attention to the prophetic word, pointing out that this rising power is but a “fading power,” and that the aim of this political movement is the spread of antichristian thinking — the men of the German Baptist movement laughed at me!

Compared to the Lutheran Church, the Baptist denomination in Germany and Austria was small. The denomination only recently had been granted legal status in 1930. To avoid jeopardizing its newfound recognition, the Baptist Union of Germany encouraged its churches to be accommodating to political developments and focus on congregational life.

The union’s secretary general, Paul Schmidt, declared Nazi power was “established by God” and should be obeyed in accordance with Romans 13. Many German Baptists celebrated Hitler’s expansion of the German Reich as an opportunity for missionary work.

“Many German Baptists celebrated Hitler’s expansion of the German Reich as an opportunity for missionary work.”

For their endorsement of the Nazi party, the Baptist Union of Germany was given charge of the Union of Pentecostals of Germany in 1937 and then the Union of Free Christian Churches of Germany in 1941. These forced mergers occurred with the help of the Gestapo.

Renamed the Union of Free Evangelical Churches, Baptists now controlled one of the largest religious organizations in Europe. Paul Schmidt, himself a Gestapo agent, according to Soviet intelligence files, was appointed federal director of the UFEC. In July 1944, after the attempted assassination of Hitler in Poland, German Baptist leaders sent the fürhrer a telegram of congratulations to demonstrate their unwavering support. This was the same assassination plot connected to Bonhoeffer’s resistance work and for which he was executed at Flossenbürg concentration camp.

A prophetic voice

Like Bonhoeffer, Köster could not remain neutral.

“Overall, Köster’s aim was to be a critical and a prophetic voice. It was an enormous intellectual challenge,” Spanring said. Köster’s resolve was put to the test in 1938 when Hitler coercively annexed Austria into the German Reich. Crowds of Austrians greeted the Nazis with flags and fanfare. Immediately, the SS began rounding up the country’s politicians, intellectuals and Jewish residents as well as a number of Catholic priests who openly opposed the Nazi government. In those early weeks of German-Austrian unification, 70,000 Austrians were arrested and sent to a makeshift concentration camp.

Köster continued to preach that the Nazi ideology was “man-made hubris” and “antichristian” every Sunday morning and evening. He also delivered a similar hour-long lecture every Thursday night to his church of 300. Out of the entire congregation, only two or three families left the church in 1938, and these were Nazi sympathizers. The remainder of the church continued to support Koester. For the entirety of the war, not one member of his congregation joined the Nazi SS.

Members like Gertrud Hoffmann, who knew shorthand, would take notes on his sermons and type up the transcripts for distribution inside and outside the congregation. When the church obtained a matrix printer in 1943, members were able to distribute his sermons to their neighbors in even greater numbers. Köster preached that the church was a community; only together could they confront the Nazi threat. Baptist historians later compiled about 500 sermons preached by Köster during the Nazi occupation of Austria.

Church members weren’t the only ones present in the pews listening to Köster preach. Gestapo agents also visited Wien-Mollardgasse 35. With 900 employees, the Gestapo office in Vienna was one of the largest in the German Reich. Köster had several meetings with the Gestapo, including one in 1942. That day, the agent interrogating Köster urged him to accept the Nazi worldview. In response Köster told the man, “Dear Sir, if I were to accept your worldview, I would have to confirm publicly that this kind of worldview will accomplish victory. That I cannot do. You cannot expect that from me, since it is my view that this worldview will end in a terrible catastrophe.”

At a Thursday night lecture in 1943, he described to those listening how he would pray before he “had to go to summons and the like.” The next Sunday, Köster encouraged his congregation to continue gathering for worship even if he was “caught.” Unlike Bonhoeffer and other many other clergy who defied the Nazis, Köster never was jailed or deported to a concentration camp.

In a sermon from Jan. 2, 1944, Köster told his congregation: “I was always conscious of a mysterious divine command to preach God’s word openly. God desires to be heeded and understood! I endeavored to go to the limits.”

He did just that when he spoke out against the grotesque antisemitism of the Nazi ideology and worked to protect Jewish people.

Köster believed God loved the world and everyone in it. In a 1934 article, he wrote: “The Holy Spirit shows us the brother in man. … What do social and racial differences mean to him! ‘They are all one in Christ.’”

Protecting Jews

Unfortunately, many Austrians shared the Nazis’ antisemitic views and after the annexation in 1938 turned on their Jewish neighbors, whom they robbed and publicly humiliated by forcing them to clean public toilets with their bare hands and eat grass like animals. The Mauthausen concentration camp, constructed a few months later, would become the organizational hub of more than 60 smaller camps throughout Austria.

Most of the Jewish people in Austria lived in Vienna, and Köster’s church played an active role in their protection. He deliberately preached from the Hebrew Bible and insisted it was God’s word while other theologians rejected those texts out of deference to Nazi ideology. Köster also emphasized the role of the Jewish people as “God’s elect,” whom God would not desert.

While it is difficult to know everything Köster’s congregation did to help the Jewish people of Vienna, German church historian Andrea Strübind says the church at Mollardgasse 35 was a “home for persecuted Jews and Jewish Christians.” Before the war, the church had 50 Jewish members. During the Nazi occupation, they sheltered many more. In 1941, when the Swedish Lutheran Israel Mission no longer could help Jewish people flee Nazi Germany, Köster accepted them into his congregation.

100-year celebration

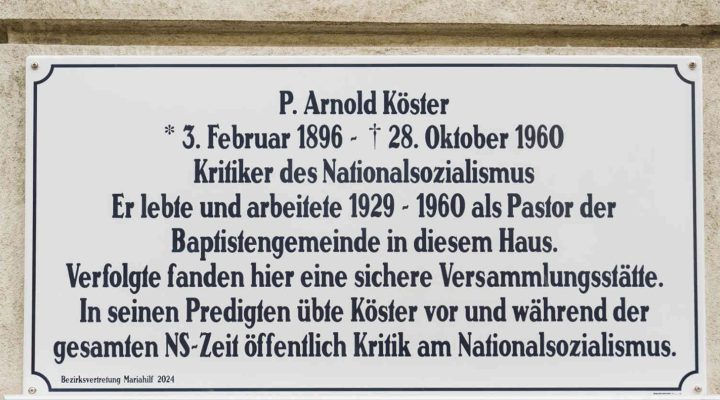

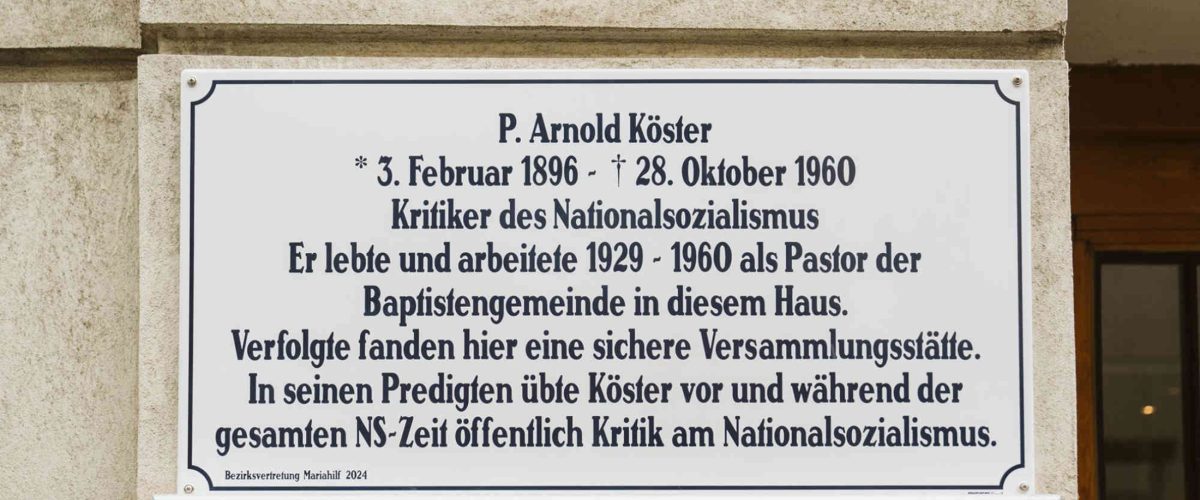

Arnold Köster continued to serve his Vienna congregation until his death in 1960. On Friday, Sept. 13, 2024, the church celebrated 100 years of ministry in their building at Wein-Mollardgasse 35. The Vienna city council erected a plaque in Köster’s honor.

Lutheran Bishop of Vienna Michael Chalupka gave a short speech at its unveiling, saying: “That Arnold Köster was not imprisoned may be a matter of chance. But it also shows it was possible to speak, and to speak publicly.”

Ewan King, minister of Heath Street Baptist Church in London, was present at the celebration and believes “if many preachers had preached like Köster … they would very well have contributed to a decline in the authority of the (Nazi) government and its support among the population.”

When asked what Arnold Köster might say to Christians today facing another rising tide of fascism, Spanring replied: “Making a historical person give advice to the present generations is tricky. I suppose what Köster would ask church leaders (and every Christian disciple) is: Are you deluded (investing in political leader messianic hope) or are you accommodating (adopting a disengaged and apolitical stance)? He attempted a ‘prophetic’ calling, which was most certainly an exhausting and dangerous task.”

We would do well to listen and learn from Köster example in our own “dark and mysterious” time.

Kristen Thomason is a freelance writer with a background in media studies and production. She has worked with national and international religious organizations and for public television. Currently based in Scotland, she has organized worship arts at churches in Metro D.C. and Toronto. In addition to writing for Baptist News Global, Kristen blogs on matters of faith and social justice at viaexmachina.com.