James Baldwin was my exact age — 63 — when he died in 1987. At the time of his death, he had written essential novels, plays and essays and had given a multitude of powerful speeches, including a 1965 debate against conservative intellectual William F. Buckley at the Cambridge Union where he masterfully argued the affirmative on the question, “The American Dream is at the expense of the American Negro.”

On that occasion, a room full of white Cambridge scholars — the present and future masters of the universe — rose to give him a standing ovation, and in the 1960s, James Baldwin was at the bright center of the universe.

His 1963 book The Fire Next Time rose to the top slot on the New York Times bestseller list and remained on the bestseller list for more than 40 weeks. He made the cover of TIME magazine, back when such things mattered. His incendiary play Blues for Mister Charlie was staged on Broadway, and Attorney General Robert Kennedy asked him to bring together a group of Civil Rights leaders and allies (not to include Martin Luther King Jr.) for a top-level hush-hush meeting in the Kennedy penthouse in Manhattan that did not, sadly, go very well.

All this notice, attention, notoriety was a lot for this gay Black man from Harlem who had fled the church and the United States for a truer life in France, and you can feel him wrestling with relevance in the things he wrote and said in those years, just as you see him willingly embracing the role of “witness” to racism and injustice in the United States that grows out of his expanded portfolio.

“James Baldwin launched attacks on the color line, on every line people draw to differentiate themselves from others.”

Some celebrities launch skin care lines. James Baldwin launched attacks on the color line, on every line people draw to differentiate themselves from others.

In the later years of his life, Baldwin’s star dimmed. His willingness to embrace love and grace toward the White Devil stood at odds with Black Power activists and the Nation of Islam, and his later productions didn’t seem to have the same literary and political heft. Although he was working at the time of his death on a masterful play, The Welcome Table (I have read drafts of it in manuscript), he had been reduced to a sort of great gray eminence in the South of France, visited by a new generation of Black writers and thinkers including historian Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Toni Morrison, who described at his memorial service in New York City how Baldwin “gave me a language to dwell in, a gift so perfect it seems my own invention. I have been thinking your spoken and written thoughts for so long I believed they were mine. I have been seeing the world through your eyes for so long, I believed that clear, clear view was my own.”

At the time of his death, I fear Baldwin felt he no longer was relevant, no longer important, despite the affirmations of those who loved him and admired him, despite his many accomplishments.

He may have worried he was no longer of use.

But the truth is, in this centenary year of James Baldwin, he is more relevant, more important, than ever. We live in an America where white supremacists want to roll back racial progress, to forget racial histories, and James Baldwin stands up and tells us no, tells us through his words and tells us through his work.

I am a huge fan of the Museum of African American History and Culture on the National Mall, a museum designed to deploy Black counter-myths against 400 years of American racism. To show the history of America is also, inextricably, the history of African Americans, and that any history that doesn’t accommodate this truth is inadequate and does a disservice to all of us.

Unlike, say, the Museum of American History, where your experience of the exhibits may be contextual but not emotional (short of whatever emotion you yourself may bring to seeing Fonzie’s leather jacket), the MAAHC (like the Holocaust Museum in Washington, like the 9/11 Museum in Lower Manhattan) is immersive. Its display of exhibits and its design are intended to provoke responses. (Some responses may be more attuned to the experience than others; when President Donald Trump toured the museum with Director Lonnie Bunch, an exhibit about the Dutch role in the slave trade prompted him to turn to Bunch and say, “You know, they love me in the Netherlands.”)

But regardless of how visitors process the experience, everyone who follows the designated path through the museum gets funneled from exhibits on the origins of the slave trade in Africa through those on the Middle Passage to slavery in the colonies and then, in the new nation of America. The lowest level of the museum, the beginning of our American story of race, is dark, the walls and ceiling feel close and get closer, and whether you realize it’s supposed to evoke holding cells and over-crowded slave ships, you cannot help but feel a sense of dismal claustrophobia.

“It is almost too much to bear, which may be why so many today do not want to bear it.”

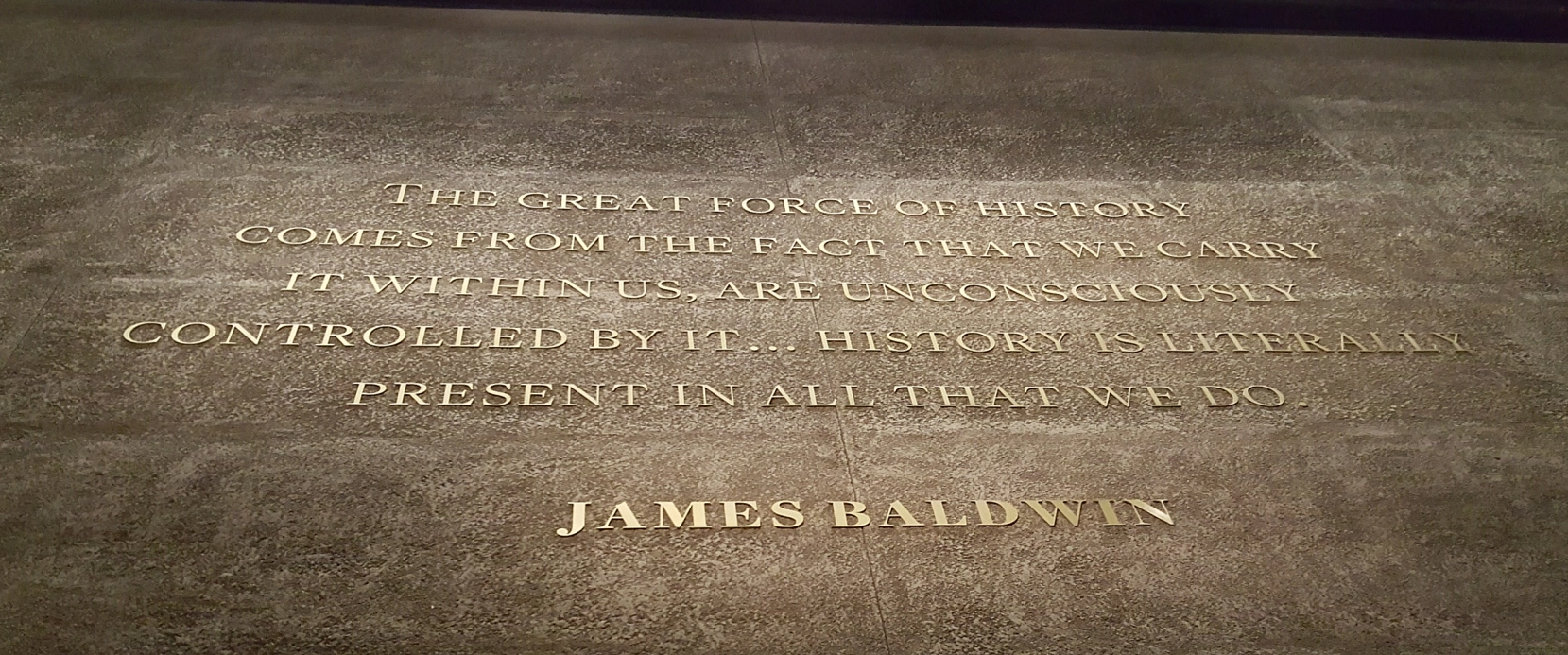

Then as you twine upward through the museum and through our history, visitors may feel moments of deep sadness or even anger. All this dark history, all this pain, all this loss. It is almost too much to bear, which may be why so many today do not want to bear it. But to live in this country and to remain in ignorance is not an option. On the massive gray back wall, looming over the lower floors, is this reminder from Baldwin: “The great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it. … History is literally present in all we do.”

This history we are witnesses to is painful, and it is all too true. Baldwin wrote it and wrote about it, and whether we are in the Age of Kennedy or the Age of Trump or the age of whatever comes next, his witness remains all too necessary.

Hatred seems to be ascendant. Hatred for gay and trans people, for people of color, for people on the margins. Baldwin would have recognized and rued these impulses.

But somehow, to my great consternation and inspiration, he managed to believe we were capable of more. In his books and in his late interviews, he told us that even after all he’d seen, even after everything he’d lost, he still held onto this belief: “I know that we can be better than we are. That’s the sum total of my wisdom in all these years.”

James Baldwin (checked shirt) with leaders of the Civil Rights Movement at the conclusion of the Selma to Montgomery Civil Rights March on March 25, 1965, in Montgomery, Alabama. (Photo by Morton Broffman/Getty Images)

I can’t tell you how much I need that wisdom 100 years into our life with James Baldwin.

Every day, it feels like Americans become more hateful, more ignorant, more willing to let go of the most basic teachings on love and justice.

And then I reflect on Baldwin, who experienced everything I am seeing — and who experienced it without the benefit of being a straight white middle-class Christian man.

If he could hope, then I can hope.

We can hope.

The night has been dark before, but James Baldwin reminds us light is not only possible, but promised if we will be faithful witnesses to what we can be.

Greg Garrett is an award-winning professor at Baylor University, where he is the Carole McDaniel Hanks Professor of Literature and Culture. One of America’s leading voices on religion and culture, he is the author of 30 books, most recently the novel Bastille Day and The Gospel According to James Baldwin: What America’s Great Prophet Can Teach Us about Life, Love, and Identity. He is currently administering a major research grant on racism from the Eula Mae and John Baugh Foundation and finishing a book on racist mythologies for Oxford University Press. Greg is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church and Honorary Canon Theologian at the American Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Paris. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

Related articles:

In the footsteps of James Baldwin: An excerpt from The Gospel According to James Baldwin | Opinion by Greg Garrett

Stranger in the Village: James Baldwin and inclusion | Opinion by Greg Garrett

Baldwin, Bobby and the necessity of hard conversations | Opinion by Greg Garrett