In September, I left the United Methodist Church for an Alliance of Baptists congregation. While I hold a master of divinity degree and knew the broad strokes of Baptist history and have worked alongside Baptists for several years, I didn’t know the finer details of the tradition’s more recent history.

Like a good convert, I’ve spent the last few months immersing myself in the history and writings of the early Anabaptists and Baptists. I’ve read both primary sources (including diaries, testimonies and the various confessions of faith) and secondary sources (like Doug Weaver’s In Search of the New Testament Church and Walter Shurden’s The Baptist Identity).

“Individual access to God and the freedom and responsibility that comes with it is a key reason I was drawn to the Baptist tradition.”

As a former Methodist, I claim the Arminian General Baptist tradition. In that vein, I’ve been reading much about Arminius and the Arminian influences on the early Baptists while avoiding the readings from the early Calvinist influences. I am not now — nor will I ever be — a Calvinist.

However, one of the beautiful things about the historic Baptist tradition is the emphasis on soul competency and the “priesthood of the believer” which all early Baptists — whether Arminian or Calvinist — held dear. Individual access to God and the freedom and responsibility that comes with it is a key reason I was drawn to the Baptist tradition.

Baptists always have valued freedom of conscience for every person — regardless of their religion. This distinctive is alive today in the work of Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty and the many Baptist churches and affiliations across the country committed to the separation of church and state.

Last week, while working on an article about how Christian extremists misuse the book of Esther, I came across Al Mohler’s first convocation speech at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in August 1993. From there, I fell down a rabbit hole into a pit of darkness reading about the fundamentalist takeover of the Southern Baptist Convention. Like watching a horrific trainwreck, it was impossible for me to turn away.

The Abstract of Principles

After watching his first convocation speech, I watched Mohler’s 1993 Q&A with the students of Southern as they fought to preserve their seminary’s theological and academic integrity from the fundamentalists.

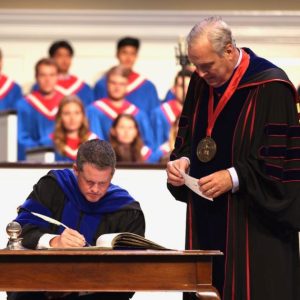

Al Mohler watches a faculty member sign the Abstract of Principles at Southern Seminary. (SBTS photo)

One of the changes I noted was how Mohler took the century-old tradition of seminary faculty ceremonially signing the school’s Abstract of Principles — which was drafted by the founding faculty two years before the start of the Civil War — and turned it into forced declaration of agreement with an 1859 creed.

For decades, new faculty had signed the document as a sort of initation into the school’s traditions, but Mohler upped the ante. In seeking the presidency, he had written an exegesis of the Abstract outlining his intent to take the then-progressive school backward a hundred years.

Under the guise of returning the seminary to its pre-Civil War glory days — you know, when Blacks were enslaved and women couldn’t vote — Mohler forced faculty to sign the creed and really mean it.

Mohler has written: “Confessional seminaries require professors to sign a statement of faith, designed to safeguard by explicit theological summary.”

I thought Baptists didn’t do creeds

The very notion of a Baptist forcing other Baptists to sign a creed is antithetical to the confessional Baptist heritage, and Southern’s faculty should have known that before Mohler. But his interpretation and demands upped the ante severely. That was his intent. It’s how he drove out tenured faculty.

The point is this: Baptists don’t do creeds. In fact, our Baptist spiritual ancestors literally died over this issue.

Although the architects of the “conservative resurgence” in the SBC did not share Mohler’s Calvinistic theology, he was useful to them. He helped achieve their goal of ridding the denomination of perceived “liberals.”

Eventually, the SBC purged all six of its affiliated seminaries of all but the most conservative Baptists. With total control of the seminaries, the SBC then turned its attention to the various mission agencies.

Missionaries — some who had lived overseas for 20 to 30 years — were forced to sign creeds similar to the one Mohler enforced at Southern. Some of their correspondence with International Mission Board President Jerry Rankin was published by the now-defunct Texas Baptists Committed, but their responses live online and are worth reading in their entirety.

As I read the news articles, personal testimonies and open letters from the 1990s and early 2000s, I kept coming back to what many of the Baptists being purged from the SBC were saying: Baptists are confessional, not creedal. They also are congregational with the spiritual and doctrinal authority resting within churches, not denominations.

Once Baptists sign onto specific doctrinal creeds, they no longer are Baptists. Of course, Mohler and Rankin denied what these Baptists were being forced to sign were really “creeds.” Some very brave Baptists publicly called them liars for pretending these doctrinal statements were anything but.

Today, the SBC’s doctrinal statement known as Baptist Faith and Message has been turned into a creed. Any level of cooperation with the SBC requires acquiescence to this statement that affirms biblical inerrancy and female subordination. Within the text, the historical Baptist conviction of soul competency and of the priesthood of the believer were rewritten.

Commenting on this change in 2000, Mark Ray of First Baptist Church of Hartselle, Ala. wrote:

“Priesthood of the believer” was changed to “priesthood of believers” (plural). Our ancestors endured persecution in order to secure freedom of “soul competency” for future generations. Individual access to God through Christ alone — no other human mediator — has been a hallmark Baptist doctrine. BF&M 2000 rekindled old fears. A new plural wording of “believers” suggests individual views are less valid than majority edict. And despite having been called its most important section by Herschel Hobbs, they omitted the 1963 preamble — which explains confession (what Baptists generally believe) vs. creed (what Baptists must believe).

Baptists are confessional — not creedal.

The power and the glory

Lest history forget though, the remaking of the SBC — the wealthiest religious organization in the United States outside the Catholic Church — wasn’t just about doctrine. It was as much about greed and the quest for domination as it was over doctrine.

Having just experienced the disaffiliation of churches from The United Methodist Church, this sounds eerily familiar to me.

While in the SBC the fundamentalists took over the denomination rather than leave, in the UMC the fundamentalists began departing in droves once the denomination offered individual congregations the option to buy communally held church property for pennies on the dollar. In the UMC, what began with the fundamentalist biblical inerrantists leaving over doctrinal disagreements soon morphed into a mass land-grab turning otherwise theologically moderate churches into first-rate grifters.

“Greed and the quest for domination have harmed Christian communities of all stripes.”

Greed and the quest for domination have harmed Christian communities of all stripes.

Let’s call them BINOs

Whether congregations left the United Methodist Church because of greed or because they knew the remnants were about to remove the hateful language about our LGBTQ siblings from the Discipline, they all framed their departure as related to “orthodox” Wesleyan beliefs and understanding God’s grace. Specifically, the fight was said to be over their belief in the inerrancy of Scripture.

As a then-Methodist who understands inerrancy contradicts the gospel, when distinguishing which “Methodist” denomination I was a part of, I became accustomed to saying “the real one.”

I know I’m new to the Baptist fold, but it seems to me once Mohler, Rankin and Patterson forced creeds on SBC churches, seminaries and missions, they abandoned the very principles that have distinguished Baptists since the 17th century.

I’d therefore like to suggest we stop referring to them as Baptists.

In 1992, Republicans began using the term RINO (pronounced like the animal rhino) to refer to Republicans they felt had abandoned the party’s core principles. The moniker, which stands for “Republican in Name Only,” stuck and recently made a comeback.

What’s good for the goose is good for the gander.

I’d like to suggest we start referring to today’s Southern Baptist leaders as BINOs — Baptists in Name Only.

Of course, I’m only joking.

Sort of.

Mara Richards Bim serves as a Clemons Fellow with BNG and as program director at Faith Commons. She is a spiritual director and a recent master of divinity degree graduate from Perkins School of Theology at SMU. She also is an award-winning theater artist and founder of the nationally acclaimed Cry Havoc Theater Company which operated in Dallas from 2014 to 2023.

Related articles:

Thirty years later, no one has reshaped the SBC more than Albert Mohler | Analysis by Mark Wingfield

Southern Seminary president affirms fidelity to Abstract of Principles

BGCT tells Kevin Ezell no on 2000 Baptist Faith and Message