Christmas and New Year are fascinating seasons for scholars into temporal studies, the emerging academic field concerned with the ways humans understand time, author and cultural historian Alexis McCrossen said.

“Holidays are special moments in time and special moments on the calendar — they represent time out of time,” said McCrossen, professor of history at Southern Methodist University in Dallas and author of the forthcoming book

“This year, Christmas is on a Wednesday, which is usually a normal day when we go to work, have our normal routines, maybe go to a Bible study. But even if you are not Christian, Christmas will supersede a normal Wednesday because it is an especially charged time when everything we do changes.”

New Year’s also represents a break from the routine, but with a more intentional focus on the passage of time, she added. “It is a special time because it gives rise to people’s thoughts about time itself. We think about the past, present and future and say things like, ‘Time flies by so fast.’”

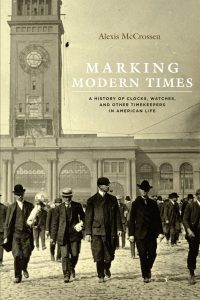

For McCrossen, the fascination with time as an area of research runs deep and has produced books such as Marking Modern Times: Clocks, Watches and Other Timekeepers in the United States and Holy Day, Holiday: The American Sunday.

The pursuit places her in the midst of an expanding discipline populated with psychologists, economists, political scientists, sociologists, historians and religion scholars.

“We are interested in different questions related to time and temporality, orientation to the clock and the calendar, toward natural time and the ways people understand the life cycle,” she explained. “Time keeping and temporality are fundamental parts of the human experience.”

Calendars help people track time cycles, milestones and sacred days and seasons, McCrossen said. “The calendar is one of the fundamental units of time keeping, and one of the fundamental ways we demarcate and think about the passage and meaning of time.”

In the American context, the role of the calendar in shaping faith goes back to before the founding of the nation to the 16th century.

“Reformed Protestants sought to reshape the practice of religion by getting rid of observances they saw as remnants of paganism and remnants of the corruption of the Catholic Church,” she said.

“Reformed Protestants sought to reshape the practice of religion by getting rid of observances they saw as remnants of paganism and remnants of the corruption of the Catholic Church,” she said.

The Puritans doubled down on the effort in the Colonial period by trying to purify the church and society from any occasion, including Christmas or New Year’s, that could rival Sunday as ultimately sacred.

“They said, ‘We have to get rid of these holidays and clean this calendar up because we need to get focused on our duties as Christians.’ They saw that the Bible says, ‘Sbserve the sabbath,’ so every Sunday was a red-letter day in the almanac to show it was a holy day, and all the other days were printed in black. The only major occasion they would observe was Easter, which is always on a sabbath.”

With the exception of Catholics, most in the U.S. remained suspicious of holidays until after the Revolutionary War when wealthy Americans, inspired by British royal family traditions, began exchanging gifts around New Year’s.

The idea that a religiously pure version of Christmas ever existed in the U.S. does not hold water.

The practice came to look a lot like Christmas looks today, McCrossen said. “As more and more Americans living in cities became more prosperous, they used New Year’s to give presents and to reaffirm domestic ties and connections with each other. But this was largely among prosperous people, people who owned property. Others used the occasion as an excuse to get drunk, get rowdy and get in fights.”

Christmas slowly began its return to the calendar during the 1820s and 1830s as commerce sought the disposable income of the nation’s growing middle class, she said. It wasn’t until after the Civil War that “Christmas becomes a domestic holiday observed in homes and in churches, and New Year’s becomes the more public, rowdy event.”

The idea that a religiously pure version of Christmas ever existed in the U.S. does not hold water, she added. “The corruption of the holiday is what a lot of people are concerned about, the materialism. But in some ways, it’s on us, not on the marketplace. The marketplace just provides what people ask for.”

Even Santa Clause and Christmas trees are not original to Christmas in the American context, evolving instead from New Year’s traditions, she continued. “Christmas was really a minor celebration and New Year’s developed from celebrating the day (Jan. 1) to celebrating the moment of midnight the night before.”

The development of the New Year’s Eve countdown exemplified by the Times Square ball drop in New York City didn’t come about until the 1970s, McCrossen said. “It’s a very modern way of thinking about time and expresses a lot of the anxieties and issues we have about time these days.”