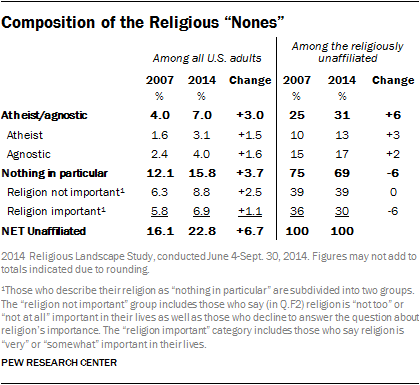

The number of atheists in the United States has “roughly doubled” since 2007, up to 3.1 percent of the adult population, according to the Pew Research Center. When combined with the rise of Americans who claim no religious affiliation, the survey may be another sign the nation is turning its back on faith.

“But one thing is for sure,” Pew’s Michael Lipka wrote about the data. “Along with the rise of religiously unaffiliated Americans (many of whom believe in God), there has been a corresponding increase in the number of atheists.”

Pew also found that the number identifying as agnostics has risen from 2.4 percent to 4 percent between 2007 and 2014.

But some experts who track the impact of religious decline on the American church say there may be more than one way to interpret the new data. And they insist people of faith don’t need to despair in the face of these trends if they are willing to embrace radical hospitality.

But some experts who track the impact of religious decline on the American church say there may be more than one way to interpret the new data. And they insist people of faith don’t need to despair in the face of these trends if they are willing to embrace radical hospitality.

Author and filmmaker Thom Schultz says it’s far too early to panic about the June 1 survey. The 1.5 percent increase reported by Pew likely is made up in part of longtime atheists who previously hid their views.

“Culturally, we’ve come quite a distance to where atheists and agnostics feel more comfortable coming out, as it were,” says Schultz, director of the new film When God Left the Building: The Exodus of America’s Faithful and What’s Next.

“It hasn’t been studied enough to know if they were atheists in 2007 who were just afraid to admit it,” says Schultz, also author of Why Nobody Wants to Go to Church Anymore.

To some extent, some Americans must feel safer going public with their atheism, given the flurry of conversations in recent years about the Nones — those who profess no religious affiliation but who, in many cases, hold spiritual beliefs.

The Pew survey also found that the number of U.S. adults who believe religion to be unimportant stands at 6.3 percent — a 2.5 percent gain during the survey period. The overall number of unaffiliated jumped to 22.8 percent of the population. That was a 6.7 percent increase.

“There is definitely a movement out there where people are feeling freer to talk and think about these things,” Schultz says.

Disdain for authority

The hard numbers support the existence of such a movement, says Josh Packard, an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Northern Colorado who specializes in the sociology of religion.

Packard notes there are 60 million adults in the United States who once attended church but don’t do so anymore.

Some of them are known as the “Dones,” who remain Christians but say they are finished with institutional Christianity, says Packard, co-author of Church Refugees: Sociologists reveal why people are DONE with church but not their faith.

But many are done with faith itself when they leave church, he adds.

“Another reason [for leaving] is that you stop believing in God or you become agnostic.”

Of those 60 million Americans who have quit church, about half maintain a faith identity, and about half don’t, Packard says.

“That does not mean there are 30 million atheists who used to go to church. But a number of them will be atheists.”

Packard says there is no hard evidence about why people leave religion for atheism. But there are hints.

“We know there is a lot of dissatisfaction with the inconsistencies” of organized religion, Packard says. “A lot of atheists see it as a real rigid approach to faith that doesn’t allow for the full freedom … to engage.”

Altogether, the evidence offers clergy and congregations healthy ways to address the issue of Dones — both the believing or unbelieving kind.

“Don’t look further than your own nose,” he says. “There are people in your pews right now asking those kind of questions.”

And remember that it is relationships, not authority, that keeps people in church, he adds.

“Poll after poll shows a distrust of official sources of authority.”

Practicing radical hospitality

Schultz says he’s had the opportunity to converse with atheists who have abandoned Christianity. As Packard alluded, many sat in church pews for years harboring questions and doubts about God, the Bible and faith.

They felt unsafe to express those feelings and beliefs at church or with their ministers, Schultz says.

“They feel this hard sense of rejection not only of their beliefs, but of them as people.”

During those conversations, he’s found atheists surprised and grateful to meet a Christian willing to discuss these matters with them.

That’s what the church must do to prevent more people from leaving or or at least to be open to judgment-free communication with those who do leave, Schultz says.

But for that to happen, Christians must abandon the idea that accepting atheists equates to endorsing their beliefs.

“That’s where the church gets all tangled up in this thing,” Schultz says.

“The whole idea of accepting and being … radically hospitable — that is especially important when encountering atheists.”