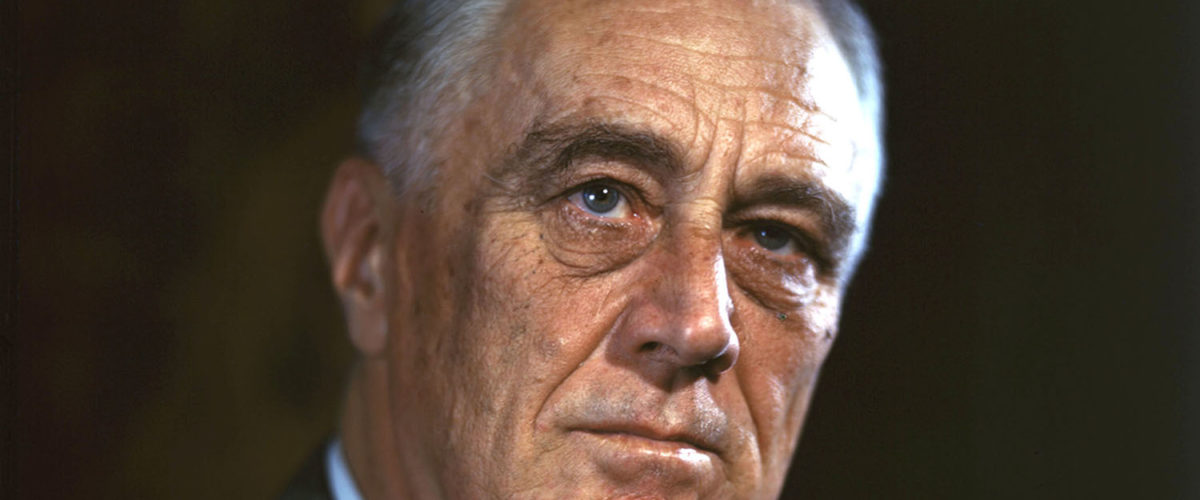

Franklin Roosevelt’s powerful biblical imagery brought hope to a nation in the depths of an economic and social crisis, and instilled support for his progressive social vision.

In March of 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt took presidential office in a country that was arguably far more divided than the one the new president faced in 2017 on inauguration day. In 1933, the country’s mood was deemed dangerous enough that machine guns were trained on the crowd gathered to hear Roosevelt’s inaugural speech. Eleanor Roosevelt called the crowd’s sullen mood and willingness to do anything he might ask of them “a little terrifying.”

Events everywhere were terrifying. Farmers across the country were battling police. Federal troops had fired on protesting war veterans and their families. Violence between labor and management was flaring across the country. Confidence in democracy was so depleted that many believed dictatorship a better option.

Expectations of the new president were low among the country’s most trusted pundits. But they would soon change their minds. Greeting the country as “my fellow Americans,” FDR began an inaugural address that proved to be one of the most amazing 20 minutes in American history. Speaking with fewer than 2,000 words, he transformed angry, despairing America into a country filled with hope. He did it using his own charisma and amazing rhetorical skills. He did it by proposing specific and sweeping changes. But that wasn’t all.

Expectations of the new president were low among the country’s most trusted pundits. But they would soon change their minds. Greeting the country as “my fellow Americans,” FDR began an inaugural address that proved to be one of the most amazing 20 minutes in American history. Speaking with fewer than 2,000 words, he transformed angry, despairing America into a country filled with hope. He did it using his own charisma and amazing rhetorical skills. He did it by proposing specific and sweeping changes. But that wasn’t all.

Among the most potent of his weapons against the nation’s despair was the Bible. He evoked Scripture throughout his first speech as president to describe the losses America had suffered, to assign blame, to comfort the afflicted and to propose remedies — a practice he would continue throughout his years in office. He used Scripture to invest his leadership with grandeur and his causes with power. He also used the Bible to pull Americans together in spirit, united around their deepest, most sacred values.

In 2017, the nation’s new president wasn’t likely to include nearly so much Scripture in his inaugural speech. Judging by the presidential race, the inaugural address wasn’t likely to contain any Christian references at all. Scripture of any kind was largely absent from the election discussion. Donald Trump infamously flubbed one attempt to use the Bible when he called First Corinthians, “One Corinthians.” Hillary Clinton referenced her faith, but only rarely. In her speech at the Democratic National Convention, she repeated “the words of our Methodist faith: ‘Do all the good you can, for all the people you can, in all the ways you can, as long as ever you can.’” That’s a worthy admonition and it may be famous among Methodists, but it isn’t from the Bible.

In 2017, the nation’s new president wasn’t likely to include nearly so much Scripture in his inaugural speech. Judging by the presidential race, the inaugural address wasn’t likely to contain any Christian references at all. Scripture of any kind was largely absent from the election discussion. Donald Trump infamously flubbed one attempt to use the Bible when he called First Corinthians, “One Corinthians.” Hillary Clinton referenced her faith, but only rarely. In her speech at the Democratic National Convention, she repeated “the words of our Methodist faith: ‘Do all the good you can, for all the people you can, in all the ways you can, as long as ever you can.’” That’s a worthy admonition and it may be famous among Methodists, but it isn’t from the Bible.

In the vice presidential debate, Mike Pence summoned up one of the most long-running and divisive political fights in America — opposition to the country’s laws on abortion — by citing a verse that proclaims God “knew you when you were yet in the womb.” Former missionary and vice presidential candidate Tim Kaine countered by disparaging Trump with a less well-known verse from Luke: “From the fullness of the heart, the mouth speaks.” At another time, when Kaine cited God’s proclamation in Genesis that God’s creation was good, to bolster progressive acceptance of diversity, he was pummeled by evangelical scholars.

Part of the reason Scripture was so absent from the discussion, especially among Democrats, has to do with how the Bible and even Christians themselves have been most prominently portrayed in recent years. The country’s most conservative Christians, overwhelmingly Republican, have dominated the public square for as long as most Americans can remember. Often known for their combative stance against cultural changes, they have come to represent all Christianity in the minds of many.

During those years, Judeo-Christian scripture has been used by politicians almost exclusively to define differences among groups. A conservative politician using as much Scripture as Roosevelt did would most likely be seen as issuing a call to battle aimed toward special interest groups, an encouragement toward aggressive opposition rather than unity. When evangelical President George W. Bush included even vaguely Christian references, sometimes nothing but phrases from popular hymns, he was accused of using “code words,” calls to action that only Christian fundamentalists would respond to.

It should be noted that Roosevelt himself often used the Bible to declare and define his own wars — against unholy greed during the Depression and later against the ungodly Nazis during World War II. He was undeniably divisive, one of the most hated and most loved of America’s presidents. But perhaps more importantly as a model for our times, he was a leader who cast a vision that could galvanize Americans to solve problems that seemed insoluble. He used Scripture as a way to infuse his faith — religious and secular — into average people during a time of great and unprecedented economic and social change — a time much like our own.

It should be noted that Roosevelt himself often used the Bible to declare and define his own wars — against unholy greed during the Depression and later against the ungodly Nazis during World War II. He was undeniably divisive, one of the most hated and most loved of America’s presidents. But perhaps more importantly as a model for our times, he was a leader who cast a vision that could galvanize Americans to solve problems that seemed insoluble. He used Scripture as a way to infuse his faith — religious and secular — into average people during a time of great and unprecedented economic and social change — a time much like our own.

Today the most remembered words of FDR’s inaugural speech are “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” but press accounts of the day gave that phrase only passing mention. More stunning to his 1930s audience was his repeated characterization of bankers and businessmen as the “unscrupulous money changers.” The term money changers used alone, without any reference to the temple or to Jesus, was enough to signal God’s displeasure with great wrongdoing to a 1933 crowd.

FDR began his address on a decidedly spiritual note by calling his inauguration day “a day of consecration,” a phrase he had written at the top of his speech as he was waiting in the Capitol. Later he assured his listeners that America had been hit “by no plague of locusts.”

He said the people perish when their leaders have no vision, which is from Proverbs 29:18, a fact he did not mention but which would have been clear to his audience. Then he returned to the money changers, calling them “a generation of self-seekers” who have “fled the temple of our civilization.”

“We must restore that temple to our ancient truths,” Roosevelt declared.

FDR went on to define those ancient truths, and he would enlarge upon that definition during the next 12 years, often using the Bible. He would link biblical truth to legislation supporting conservation and to calls for national and international brotherhood. He would reference the Sermon on the Mount repeatedly.

It worked for him, and it kept working. But could it work today? Could any progressive or liberal politician use Scripture to inspire, lead and unite Americans today?

Probably not.

No politician, certainly no progressive politician, would attempt a speech using as many

biblical references as FDR did. While many progressives are sincerely motivated by religious faith, it’s hardly an exaggeration to say that in the public square at least, Scripture has been wrested away from them. Publicly, it has so often been used to exclude others that it can only be referred to with great caution by those politicians courting inclusivity. As a force to bring people together, the Bible does not appear to have the power it once did in America. The change hasn’t come through any alteration in Scripture, of course. It has come through great changes in those listening.

Today’s America is much more diverse, and even in nominally Christian families biblical illiteracy is common. Roosevelt could use the term “money changers” and everyone knew what he meant. Those words conjured up not only one story, but the whole story of Jesus and the extraordinary nature of his actions that day in the temple.

Today’s America is much more diverse, and even in nominally Christian families biblical illiteracy is common. Roosevelt could use the term “money changers” and everyone knew what he meant. Those words conjured up not only one story, but the whole story of Jesus and the extraordinary nature of his actions that day in the temple.

Roosevelt could refer to “a plague of locusts” without mentioning Egypt or the Exodus, or any of the other punishments God sent before the Jews were set free. For an audience that had studied the Bible in church and in school for most of their lives, those four words evoked an entire relationship of God to his people. To a country filled with people who feared that the Great Depression might signal the end of the world, such words were also a reassurance that God wasn’t angry with them.

But what that earlier audience found reassuring and strengthening, many of today’s listeners would find alienating and even alarming, no matter how gently it was intended. Today much of the audience would not know those stories at all. Others would know the stories but have no context to give them resonance and richness.

We may not be far from the day that progressive politicians who want to refer to the Bible will use the technique Christian ministers employ when they quote from Buddhist, Muslim or Jewish scriptures. They give respect to the wisdom but are careful to distance themselves a bit by introducing their story with “the Buddhists say.”

If and when politicians start introducing biblical teachings with “the Christians say,” or even “the Bible used by Jews and Christians,” it will signal a dramatic change in America’s public discourse. Many American Christians would be greatly alarmed and plunged into mourning for times past. But at the same time, a growing number of Americans might be reassured that they too are being addressed. Once their fear was eased, they might be able to listen without defensiveness. That might open a way for scripture to be broadcast more widely and to be appreciated for itself.

If shorthand usage such as “a plague of locusts” no longer signifies what it once did, perhaps politicians who want to tap into scriptural values and wisdom would be forced to retell the stories entirely. If in that telling, the stories gained new power and freshness, that might not be bad.

Those thoughts assume, of course, that the country continues in its current state with regard to Christianity. It might not. The number of white Christians is declining, but the non-white and immigrant population of America is growing. Many of them are fervent Christians. They tend to be on the more conservative side of Christianity. But they are often intimately acquainted with poverty, and they know the world outside the United States in ways most Americans never will.

At the same time, more and more evangelicals of all types are going on mission to other countries. Sometimes those experiences cause them to change their allegiance toward economic plans that favor the rich, not the poor.

Younger evangelicals, even those who oppose abortion rights and gay rights, are no longer willing to follow the Republican Party without question. The Republican Party itself may be changing.

As for progressives who love Scripture, it may be encouraging to note that Franklin Roosevelt’s familiarity with the Bible and his use of it in public addresses was far from the most valuable of the gifts his faith gave him — even politically speaking.

His innate temperament was famously upbeat. But when it failed, his faith gave him a way forward.

After contracting polio, he went through a great crisis of faith. In another person that might have been the end of belief in God and the end of his political career. But Roosevelt came to see his illness and disability as simply a test of his resolve to be of service in the way that God intended him to be.

He found hope in his darkest days through faith, and when it came time to give hope to the country in its darkest days, he was ready with an abundance of faith. While he believed faith in God was essential to bringing Americans out of the Depression, he didn’t often talk to the country about faith in God. The faith he referenced publicly was faith in oneself, faith in democracy and sometimes even faith in him.

But the vision he had for America, one that was measured by its effect on the poorest among us, came straight out of Scripture. He believed fervently in his role as a servant of God’s plan. It was that vision and that belief, formed by Scripture, that changed America forever.

— This article will be published in the Winter 2017 issue of Herald, BNG’s magazine sent four times a year to donors to the Annual Fund. Bulk copies are also mailed to BNG’s Church Champion congregations.