It has been more than a year since Tina Bailey’s friend and student was executed by a firing squad in an Indonesian jungle, but that pain is still fresh on her face.

“It’s been hard; but being a part of his life is something I would not trade for anything,” the longtime Cooperative Baptist Fellowship field personnel and artist said with a distant look in her eyes. The grief has faded, but not her passion for justice and spiritual transformation.

After more than three years teaching her friend to express his heart through painting, they spent an agonizing eight weeks awaiting either an execution date or an unlikely last-minute reprieve.

He was Myuran Sukumaran (MY-oo ron Su-koo-ma-ron) — “Myu” to his friends — once considered a notorious drug smuggler who, during a decade of incarceration, became a prison reformer and, largely under Bailey’s mentorship, an internationally renowned painter.

This unique friendship in Bali ended abruptly — many say unjustly — with Myu’s April 2015 death at the hands of the Indonesian government. On the eve of the 34-year-old’s execution, Bailey traveled 500-plus miles to the prison.

“He asked me, if it came down to it, if I would I be willing to be his witness at the execution,” recalled Bailey, who has served with her husband, Jonathan, as coordinators of arts and engagement in Bali since 1995. “I said ‘of course.’”

But at the last minute, Bailey was told Myu asked another friend to serve that role.

Not being witness to her friend’s execution left Bailey feeling dismayed and confused, but she had already witnessed something more fulfilling: Myu’s transformation into a deeply spiritual person, unafraid to face his faults or fears.

‘They were a bunch of kids’

In 2005 Myu and co-defendant Andrew Chan were branded the “ringleaders” of the Bali 9, a group of young Australian men arrested in Indonesia while attempting to smuggle 18 pounds of Indonesian heroin onto airplanes bound for their homeland. Australia’s media labeled the group of teens and 20-somethings a “drug cartel.”

Behind the headlines, Andrew and Myu were nothing like the gangsters portrayed by prosecutors during their 2006 trial, according to Bailey.

“They were a bunch of kids, low-level drug mules, looking to make some fast money,” she said.

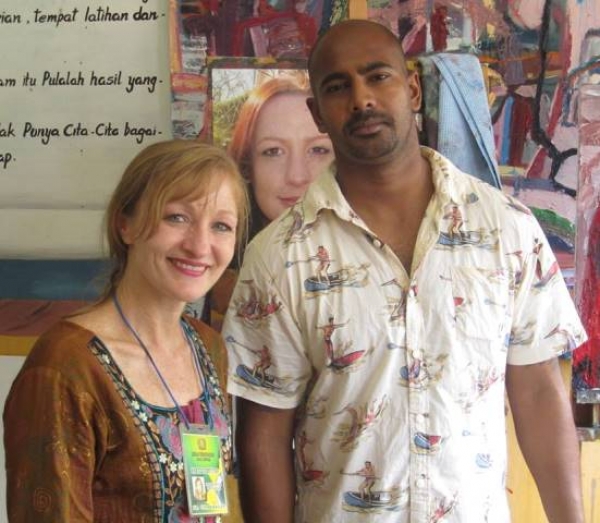

CBF field personnel Tina Bailey, and Myu Sukumaran, one of the “Bali 9” and art student in Kerobokan Prison in Bali, Indonesia. (Photo/Provided by Tina and Jonathan Bailey)

In Bali’s notorious Kerobokan Prison, Andrew went from “drug kingpin” to a repentant and emboldened pastor. Myu, the reputed gang “enforcer” and martial-arts expert, taught other inmates job skills and found an outlet for his complex emotions with a paintbrush.

Many observers believe the rabid media coverage provoked the Indonesian courts to impose the harshest sentence possible — by firing squad. While the other seven defendants received penalties from 20 years to life, Myu and Andrew became pawns in a jurisdictional dispute between the two countries and symbols of an international campaign against capital punishment.

In Australia, where the death penalty is illegal, the idea that the two faced execution by a foreign government outraged many. Although Indonesia itself opposes capital punishment for its citizens who are tried by other countries, it rebuffed Australia’s pleas to extradite the Bali 9 to their homeland for prosecution.

Australian officials pleaded for clemency, offering a prisoner swap and warning of economic and diplomatic retaliation — all to no avail. Even some reporters who had sensationalized the Bali 9 saga turned into activists trying to avert a perceived injustice.

‘A quiet strength’

During the decade their legal drama played out, Myu and Andrew transformed the lives of dozens of fellow prisoners.

Both young men grew up in nominally Christian settings in Sydney, Australia, only becoming acquainted just prior to the crime. In prison, the reputed “ringleaders” went in different directions.

“They really lived in different worlds,” Bailey said. Prisoners sometimes create routines to try to isolate themselves. “They find ways to find space,” Bailey explained.

While Andrew and Myu each came to the prison with seeds of faith already with them, they experienced a deeper and more authentic spiritual growth while imprisoned. Andrew became an outspoken Christian and ordained minister, building a strong Christian congregation inside the prison. Myu also grew in his faith in prison but his spiritual journey took a different path.

“Myu was always more private about his faith,” Bailey said. He turned introspective.

Yet he was the quiet strength other prisoners relied upon.

Myu received permission to start a computer workshop in order “to keep himself busy.” Then he started classes for graphic design, screen printing, advanced computer, sewing — some taught by outside teachers. He also encouraged another Bali 9 inmate, SiYi Chin, in starting a silversmith program. If prisoners are able to sell their products, they can keep a small percentage of the proceeds. Myu used his earnings for more equipment.

CBF field personnel Tina Bailey was invited to begin art and dance classes at Kerobokan prison. (Photo/Provided by Tina and Jonathan Bailey)

Classes were added in English, music, guitar, reflexology, even dog-grooming and surfboard building.

In Kerobokan, good behavior allowed him more visitation and free movement as well as interaction with guards and other inmates.

“It has become more like a school than a prison,” Myu recalled just before his

execution. By then, he was responsible for managing the workshops, organizing classes, controlling inmate access and making sure the whole operation ran smoothly. He also used his influence to reduce prisoner drug use and make life safer for the women in the prison.

In 2011, Myu took up a paintbrush, teaching himself to paint by copying pictures from magazines. In 2012, Myu invited Tina Bailey to teach art and drawing, later adding dance classes. It began a relationship that would last until the end, and would change both teacher and student.

“He was a very talented artist,” Bailey said. But it wasn’t always that way. Previous teachers focused on making art that “looked good” and styles that were commercially viable. Bailey urged Myu to paint from his heart. Whether or not a piece is marketable or comports with some external standard is irrelevant, she said. “It needs to be their work. Not everybody is going to become a great artist. There’s a therapeutic aspect to it,” she said. “If they can solve problems with their paintings, they can solve problems in life. We are teaching life lessons with painting.”

Painting for mental health

That approach often makes Bailey more than a teacher. As she gets to know her students, she talks with them about life; she listens; she guides, earning trust.

Each Wednesday for the last four years, Tina Bailey has traveled the 45 minutes by taxi from her home to the Kerobokan Prison. She’s in the painting studio from 9:30 a.m. to noon offering advice and conversation. She leads dance class from 1:30 p.m. to 3 p.m. Mostly female inmates attend, but the chance to spend an hour in one of the prison’s few air-conditioned rooms persuades a few men to give it a go.

The bulk of Bailey’s ministry takes place outside the prison, however. She and her husband, Jonathan, are integrated into Bali’s rich and diverse arts community, where they teach music and dance classes, conduct visual-art exhibits and collaborate with local musicians to create music in a number of cultural styles for worship and other settings.

The Baileys’ unique ministry blends the arts with spirituality. They are careful not to impose their own faith, either in the community or in the prison.

“You asked me to come in here as an artist,” Tina Bailey tells inmates. “But they know I am an ordained minister and I’m available in any way [they] need.”

For Myu, “painting was his own way of staying mentally healthy,” Bailey explained. “When a lot of visitors were coming in at the end, I would ask him, ‘What do you need me to do, Myu?’ And some days he would say, ‘I just need to paint.’”

When Bailey was first invited to teach Myu, she knew she was meeting the leader of the notorious Bali 9. But she was disarmed to learn how he had shut down a riot by inmates in 2012 by blocking their access to the guards’ armory.

When Myu first started painting, “he was a little inhibited for a while,” Bailey noted. “But in the last year of his life, he painted from his heart and his fears. The paintings he made in the last months of his life are world-class.”

Eventually his portraits — and especially self-portraits — would become his trademark.

Some art critics say those paintings show a vulnerable artist willing to dig deeply into his own pain and fear, and not one embittered by cruel justice. Some of his final paintings were displayed in a special posthumous exhibit in Australia, Canada and the Netherlands.

Seven months after the executions, Myu was named Artist of the Year in Australia, a prestigious honor presented by that country’s GQ magazine. Australia’s Curtin University

posthumously awarded Myu the associate of fine arts degree that his death prevented him from completing.

“He’s probably the most talented artist I’ve ever worked with,” Bailey said.

His artwork is now considered a “national treasure” in Australia. He sold one of his paintings to pay for the operation of a female inmate from the Philippines.

Art the path to redemption

In January 2015, Myu learned his final clemency appeal had been rejected.

“It was the last hope that I had,” Myu said in a final video tribute recorded by friends. “I’m just going to live my life and do what I’ve committed to do. I don’t think me crying and being stressed is good for my family, and I don’t think it is good for me. I have found my own passion for painting, and every single day I paint and draw, and I feel very sad that I am not going to be able to paint.”

“I’m just going to live my life and do what I’ve committed to do. I don’t think me crying and being stressed is good for my family, and I don’t think it is good for me. I have found my own passion for painting, and every single day I paint and draw, and I feel very sad that I am not going to be able to paint.”

On February 2, he and Andrew were put in line for execution. Indonesia ignored a condition of their 2006 verdicts that would reduce their sentences to life in prison if they demonstrated they had been rehabilitated.

“Although I do feel guilt for what I did a long time ago, I feel I have paid my debts for my crimes,” Myu said in the video. His execution would serve no purpose, except to allow the country’s political leaders to prove their toughness, he said.

Myu apologized to his mother, Raji, “for all the headaches and suffering I have caused. I want to make up for that … so that you don’t have to feel embarrassed any more and you could feel proud of me.”

On March 3, Myu and Andrew were removed from Bali to prepare for execution. Other inmates and even some guards cried and saluted the pair as they were led out. The condemned were transported to Nusa Kambangan, about 500 miles from Bali, a few weeks prior to their execution. On the appointed day, those to be executed are led to a jungle clearing, where they are tied to crosses, blindfolded and shot in the chest.

Bailey traveled to Nusa Kambangan three times during the eight weeks Myu and Andrew were held there. The first time she wasn’t allowed in but spent time with his mother in Cilicap, the only nearby town. The second time, she visited Myu at the request of the family, who had to return to Australia.

“It was great to see him,” Bailey recalled wistfully. “We had several hours together.” The third trip was for the execution.

Waiting at a nearby hotel, Bailey and the others watched TV reports of a chaotic scene. Myu’s mother, father, sister and brother fought through an aggressive crowd of paparazzi, media and protestors to enter the prison for their tearful goodbye.

In his final days, Myu’s jailers did grant his last request — to be able to paint as much as possible until the end. He painted feverishly — several self-portraits, a “bleeding” Indonesian flag and a Heart where all those who were to be executed signed the paintings and left their thumbprints in the paint.

Myu’s last request of Bailey was to safeguard those final paintings out of Nusa Kambangan and into his family’s possession in Australia. She did.

At the last minute, Bailey was told that pastor Christie Buckingham would serve as witness for Myu and would be joined by Andrew’s childhood pastor from a Salvation Army church. News reports had suggested officials denied the pair their requested witnesses.

“I don’t know what the reason was, but I assume it was his decision and not someone else’s and he wanted to spare me,” Bailey said. “I know there was a letter that he wrote to me that I never got.” Written from Nusa Kambangan, the letter probably explained the last-minute change of plans.

At midnight April 29, 2015, Myu and Andrew were led into the jungle with six other condemned. All eight refused to be blindfolded and sang “Amazing Grace” before guards opened fire.

Back in Bali, the inmates who counted on Bailey to be their presence at the execution struggled to understand the last-minute change.

“It was really hard to try to give comfort to those back in Kerobokan, because they all expected it to be me,” Bailey said. “I tried as best I could to help them feel good about it.”

Bailey is still “dismayed” by the saga’s awkward end and hopes Myu’s letter somehow turns up to make sense of it and provide closure.

More than a year later, the arts program pioneered by Myu and supported by Bailey continues under the leadership of an inmate from Thailand, Bailey continues mentoring there every week.

“My role is being a friend as they try to have a normal life in a place where life is not normal.”

While in Bali, Myu had painted a portrait of President Widodo with the inscription “People Can Change.” This sentiment was reflected by his brother, Chintu, when he accepted Myu’s Artist of the Year award in November 2015.

“Art was his path to redemption. Myu found a sense of inner peace when he sat in front of a canvas. He used that peace to inspire others and to find a way to do better every day. And even in the darkest places, Myu proved that people can change.”

The story was originally published at cbfblog.com.