Never underestimate the power of words or a string of words.

A news story about the Florida Board of Education — not a local school board but the state board — adopting new standards for teaching American history for children in Florida public schools flabbergasted many Americans. As did the governor/presidential candidate’s attempt to back up their “new” history of slavery.

Certainly, given the constant discovery and publication of new research, our educational standards and points of view do need periodic updating. But these 14 words are troubling: “Slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

Admittedly, a clever qualifier was inserted in the sentence: “in some instances.” But how many instances equals “some”?

“How many instances equals ‘some’?”

This string of words caught my attention because I taught American history in a majority Black junior high school in Nashville, Tenn. Perhaps I noticed it because I am currently editing a chapter on Harry Truman and civil rights for a book I am writing on the 33rd president’s spirituality — his Baptist spirituality. Particularly annoying because the announcement was made on the 75th anniversary of Harry Truman issuing Executive Order 9981 desegregating the military.

The Black Book

Those 14 words kept wandering the corridors of my mind until I sat aside some editing and walked into the Civil War section in the library and leafed through books on slavery. A book published in 1974, The Black Book, caught my eye. I never had seen the book before.

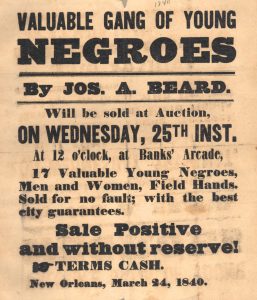

Returning to my library desk, I began reading. A photo of an announcement of a public sale of Negroes in Charleston, S.C., on March 5, 1833, leaped off the page. Perhaps this was a piece of research the “academics” on the Florida board had read to reach their new standard. The ad read:

Returning to my library desk, I began reading. A photo of an announcement of a public sale of Negroes in Charleston, S.C., on March 5, 1833, leaped off the page. Perhaps this was a piece of research the “academics” on the Florida board had read to reach their new standard. The ad read:

A very valuable Blacksmith, wife and daughter; the Smith is in his prime of life, and a perfect master of his trade. His wife is about 27 years old, and his daughters 12 and 10 years old have been brought up as house servants, and as such are very valuable.

One could purchase the family — purchase — one-half down with the balance payable in two years. Of course, there would be a mortgage on the slaves until full payment had been made. In reality, if the buyer didn’t have enough work to keep this “valuable” blacksmith busy, he could rent him out and pocket his wages. Thus, he could make the slave help pay his upkeep.

Buying slaves on “credit” surprised me. I had always supposed slave sales had been marketed to prosperous slave owners paying cash with a wad of bills.

I read that some Northerners were using the skills of free slaves but whites were objecting. “We are opposed to emancipating Negro slaves unless on some plan of colonialization” — that is, in today’s vernacular, sending ‘em back where they came from — “in order that they may not come in contract with the white man’s labor” — meaning compete against whites. On March 13, 1862, the Tammany Hall Young Democratic Committee passed this resolution. If you lean in you can hear them shouting that day’s equivalent of sound bites, “They are taking our jobs!”

The Liberator

Next, I read an editorial from The Liberator, reprinting an editorial from The Pennsylvania Enquirer, calling for legislatures in all slaveholding states to pass legislation prohibiting owners from “making mechanics” of slaves. The place of Negroes, according to the editorial, was in rice, corn and cotton fields. Not workshops.

Jobs for mechanics “should be kept for the white man exclusively,” the editorial said. “There are thousands of industrious, enterprising young men who are driven from the mechanical trade, rather than work all day side by side with the Negro.”

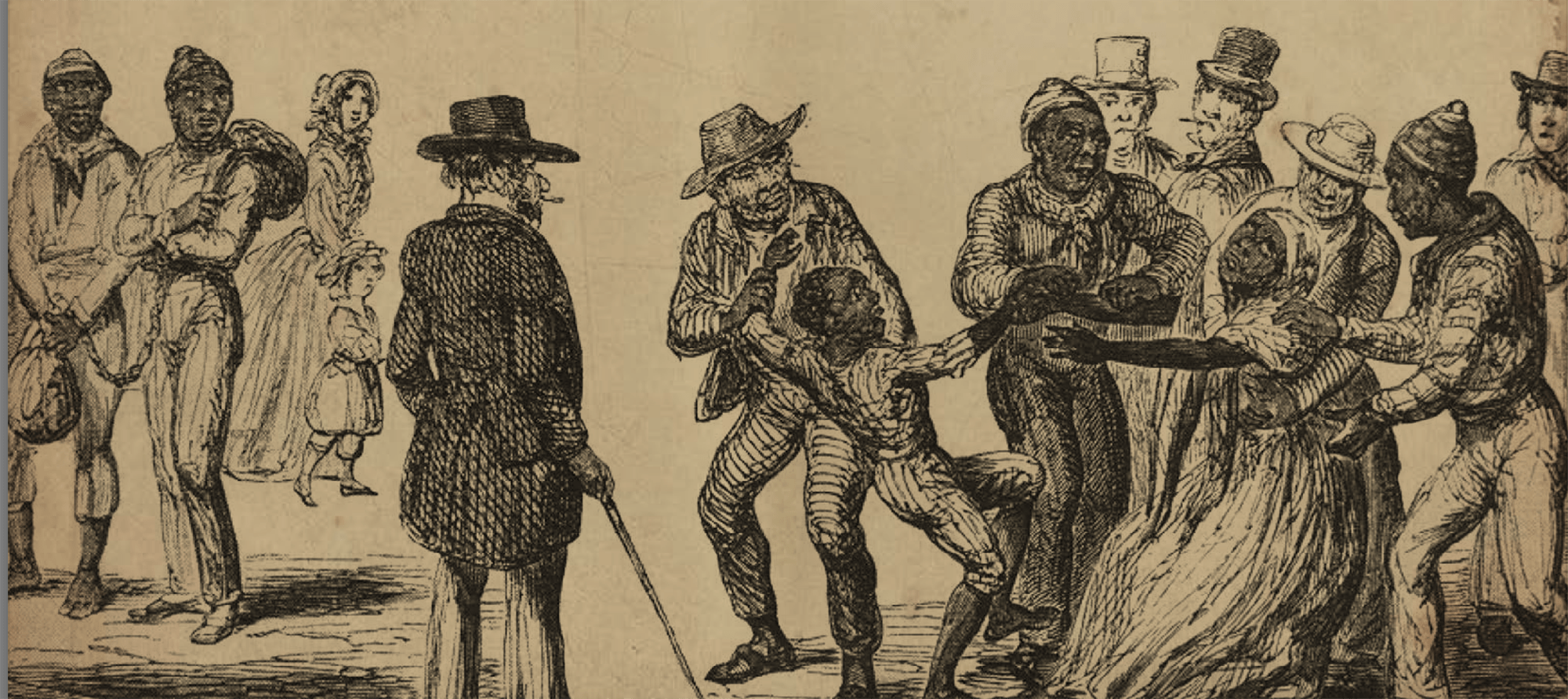

Enslaved African American mothers endured the horrors of having their children sold away. (Image from Kentucky Transportation Cabinet document)

Not to mention that the slave was probably being paid less by business owners.

The editor anticipated pushback: “We are aware that men will say we have the right to do as we please with our (emphasis added) Negroes, and convert them to any use we think proper; but that is not so.”

He continued: “No one will pretend that a master who owns a skilled mechanic ought to be or can be deprived of half of his value by a law forbidding such mechanic from working at trade which he has been at much expense and loss of time. The master, beyond dispute, has a vested right in the enhanced productiveness of the mechanic slave’s labor at a trade wherein skill, training and intelligence are as important elements as physical strength.”

Well, doesn’t the Bible support such a notion? “The servant is worthy of his hire” (2 Timothy 5:18). The Amplified Bible makes the verse plainer: “The worker is worthy of his wages” — meaning he deserves fair compensation. Which in the 1850s might have been read, “The master is worthy of the wages his slave earns working off the plantation.”

“In 1860 an estimated 600,000 Southern church members owned slaves.”

A statistic adds another troubling dimension. The Salem Observer reported in 1860 that an estimated 600,000 Southern church members owned slaves; Baptists owned some 125,000 slaves!

Mars Hill College

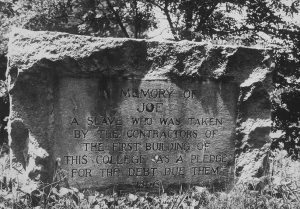

Even one Baptist institution owned a slave. In 1859, the fledgling Mars Hill College in North Carolina fell behind paying the mortgage of $1,100 on a campus building. So, Mars Hill mortgaged Joe Anderson, a slave formerly owned by a college trustee, J.T. Anderson, and “gifted” to the college. The Buncombe County sheriff seized Anderson and held him in jail until trustees paid off the mortgage.

So, the debt was paid but that narrative tidbit of institutional history smoldered.

A few years ago, in a campus presentation, professor of religion Mark Mullinax reviewed the story of Joe Anderson who is now recognized as a “founder” of Mars Hill. It is not known how long Anderson was imprisoned. Mullinax shared historical references to Anderson’s central role in the university’s founding. Anderson, apparently, is the only human known to be mortgaged for the debt of a “Christian” college.

“There are different ways to see Joe Anderson,” Mullinax noted. To underline that point, Mullinax showed video footage from university archives presenting two differing points of view. In the 1980s, Mars Hill financed a film about the founding of the college. That film portrays Brother Anderson as something of a “good” benevolent slave owner. The film offers “a re-enactment of an imagined conversation between owner and slave, friendship and love are offered as reasons why Anderson was ultimately released from prison.”

“You might expect hearing ‘We Are One in the Bond of Love’ as background music for the film.”

My! Friendship and love between a slave owner and his slave. You might expect hearing “We Are One in the Bond of Love” as background music for the film.

Another campus speaker, Emmy winning writer Melvin Bray, disagreed sharply with that narrative. It wasn’t “Poor ol’ Joe is down there in that jail. He must be missing us.” Rather Bray encouraged listeners to “follow the money.”

Money influenced Anderson’s ultimate release. “It wasn’t a moral thing, it wasn’t out of love, like ‘Oh, this is the right thing to do,’” Bray noted. Rather, “Anderson (of Mars Hill) suffered a capital loss and wanted to get Joe back because Joe made him some money” or saved the wages they would otherwise pay a white man.

GE DIGITAL CAMERA

Joe returned to the college but did not gain freedom until the end of the Civil War. But maybe he learned some skills that were useful after the war.

Joe Anderson is buried on the campus of what is now Mars Hill University. Ironically, on the grave marker erected in 1935 he is identified only as “Joe.” But then a lot of slaves did not have last names. Hasn’t some faculty member or student been offended by that omission of dignity?

I never had thought to think a Baptist institution could own a slave! I did know that buildings on one Southern Baptist seminary campus are named for former slave owners.

What’s in a word?

Today, the word “slavery” cannot be sanitized even by an education board in a former slave state. Do you remember in the story of Alice in Wonderland Humpty Dumpty’s observation: “‘When I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, ‘it means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less.’” Well, Alice was not having that. “’The question she challenged, “‘is whether you can make words mean so many different things.’” Apparently the word “slavery” means different things to Florida officials.

“Apparently the word ‘slavery’ means different things to Florida officials.”

James H. Cone, a Black theologian, described the brutality of slavery in poignant words: “Slavery meant being snatched (kidnapped) from your homeland and sailing to an unknown land in a stinking ship.” If you died, into the ocean you went. Filth, illness were rampant below deck. Slavery meant you and those you loved were not only treated like property but were legally property “like horses, cows and household goods.”

James Cone

Nowhere was slavery more demonic than on the auction block. Because, Cone noted, “no family ties were recognized” and no standards of decency prevailed. Potential buyers were free to “examine” a slave’s most intimate parts for an assessment of their sexual or breeding potential.

Thinking back to that skilled blacksmith being sold, his family members could have been sold separately if a buyer only wanted the blacksmith. One former slave, Josiah Henson, recalled the trauma, “My brothers and sisters were bid off first, and one by one while my mother, paralyzed by grief, held me by the hand.” No wonder slaves sang, “Sometimes I feel like a motherless child.”

Today, Christians — too many — sing that spiritual with no comprehension of what happened at a slave auction that made individuals feel like “a motherless child.”

Moses Grandy recalled the horror of watching his wife sold. He was “only permitted to stand at a distance and speak with her before she was taken away. My heart was so full that I could say very little.” Perhaps they were eventually reunited and lived to a ripe old age in a sharecropper’s shack. Perhaps his wife was purchased by a good Baptist who was “kind” to her and made sure she learned the plan of salvation — as well as “slaves, obey your master.”

Slave auctions rarely had “and they all lived happily ever after” endings. Cone was brutally honest in a way Florida teachers will not be able to be. Focus on the economic benefits to the slave not to the slave owner. But ignore the ugly truth:

Slavery meant working 15 to 20 hours a day and being beaten for showing fatigue. It meant being driven into the field three weeks (or less) after delivering a baby. It meant having the cost of you calculated against the value of your labor during a peak season, so that your owner (or an overseer) could decide whether to work you to death. It meant being whipped for crying over a fellow slave who had been killed while trying to escape.

Slavery meant, for women, being fondled, raped and, perhaps, being bred like horses. Or bearing an owner or overseer’s child.

Slavery meant white people, some Christian, some Baptist, achieved their prosperity by enslaving Black Africans; and out of that prosperity they donated tithes and offerings to the church or to religious institutions.

Slavery meant Southerners — and their bankers — “measured their importance” as did neighbors on adjoining plantations “by the number of Africans they enslaved” whether by purchase or by breeding.

Hopefully, but unlikely, the Florida standards will at least comment on the reality that 12 —twelve! — U.S. presidents owned slaves. Eight owned slaves while in the White House.

Hopefully, but unlikely, the Florida standards will acknowledge that the White House was built primarily with slave labor.

Hopefully, but unlikely, the Florida standards will acknowledge that the White House was built primarily with slave labor.

Hopefully, but unlikely, the Florida standards will acknowledge that slave labor was integral to every aspect of Florida in the 19th century.

Hopefully, but unlikely, the Florida standards will acknowledge that Richard A. Shine, the supervising architect and primary contractor for building Florida’s Old Capitol, was listed as a slave owner in the 1840 census. According to Edward Baptist, a Cornell professor who studied slavery in Florida, “It would in fact be shocking if the Old Capitol was not built with enslaved labor. Artisans like white carpenters and masons owned slave laborers and craftsmen.” He concluded, “Almost every building in pre-1865 Tallahassee was built at least in part with slave labor.” On field trips to Tallahassee, will teachers dare acknowledge that slaves worked on constructing such buildings?

Sound teaching?

We live in an era of “Don’t confuse me with facts.”

At the risk of being accused of proof-texting, I think of Paul’s warning in 2 Timothy 4 which I believe applies not just to theology but to contemporary politics: “For a time is coming when people will no longer listen to sound and wholesome teaching. They will follow their own desires and will look for teachers who will tell them whatever their itching ears want to hear. They will reject the truth and chase after myths.”

“The Christian school in my neighborhood advertises, ‘We teach only true American history.’”

I worry about these standards. But I also realize “myths” will be taught in some “Christian” private schools. The Christian school in my neighborhood advertises, “We teach only true American history.”

I also worry about a possible influence on preachers who decide to reconstruct some unpleasant history. I recently was outraged by one Baptist preacher who “informed” the congregation in a Sunday morning sermon:

“One hundred and fifty years ago, or 200 years ago, when the Blacks were slaves, did they ever go to Washington, D.C., and have a rally — 200 years ago — to protest against slavery? Did they? No. What did they do? Well, a lot of good people in the plantations would say, ‘Hey, it’s wintertime. Let us help build a church for you, dear folks.’ And they loved them and taught them how to read so they can read the Bible.”

I assume this pastor never had taken AP American history.

But then he put the “bow” on the package in a grand finale:

“And here’s what the Blacks did about 150 years ago: They humbled themselves. They prayed. They (sought) God’s face, and they turn(ed) from their wicked ways, and God made slavery illegal through several white presidents, right? It worked, didn’t it?”

I am always anxious when preachers say, “Right?” or “Can I get an ‘Amen.’” I wish I could have eavesdropped on the congregation’s comments as they shook the preacher’s hand at the door.

Finally, stay tuned for more new standards from the Florida board of education. What will they do with the Jim Crow era? The crowd-drawing lynchings? The beatings on the Edmund Pettis Bridge that Bloody Sunday or the bombing of Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church minutes after Sunday school ended? The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.?

I have wondered if Alex Lanfranconi, director of communications for the Florida Department of Education, is a churchgoing man. He declared, “We are proud of the rigorous process the department took to develop these standards.”

If only he had told reporters, “That’s it. I am not taking questions.”

Rather he continued: “It’s sad to see critics attempt to discredit what any unbiased observer (emphasis added) would conclude to be in-depth and comprehensive African American history standards. They incorporate all components of African American history: the good, the bad and the ugly. These standards will further cement Florida as a national leader in education, as we continue to provide true and accurate instruction in African American history.”

And yet, 14 dangerous words if unchallenged will lead to more dangerous words.

Harold Ivan Smith

Harold Ivan Smith is thanatologist and independent scholar. For 18 years he served on the teaching faculty of Saint Luke’s Hospital in Kansas City, Mo. He earned graduate degrees from Scarritt College, Vanderbilt University, and a doctor of ministry degree from Asbury Theological Seminary. His writings include A Decembered Grief, On Grieving the Death of a Father; Grieving the Death of a Mother; When You Don’t Know What to Say; When a Child You Know Is Grieving, When Your People Are Grieving: Leading in Times of Loss.

For additional reading:

- The spirituals and the Blues: An Interpretation by James H. Cone (1992)

- “The Story of Joseph Anderson” by Richard Dillingham (2010).

- “Racial, Religious Issues Shape MHU identity,” Asheville Citizen Times

- “PolitiFact Florida: Did Slaves Help Build the Old Capitol Building in Tallahassee?” by Allison Graves, Allison. (2018), Tampa Bay Times

- The Black Book by Middleton A. Harris (1974)

- The Black History of the White House by Clarence Lusane (2011)

- Truman by David McCullough (1992)