Forty-five years after a group of young Black students in Soweto, South Africa, took to the streets to protest an educational policy of the ruling South African apartheid government, leading to the death of more than 170 of them, the tragic incident and the issues it raised continues to echo around the world.

The students were opposed to the government’s decision to introduce Afrikaans language (seen by Blacks as a symbol of white supremacy and oppression in the racially divided nation) as the medium of instruction in local schools. When they came up against a police barricade, tempers soon flared and the police opened fire, leading to the death of many students on June 16, 1976.

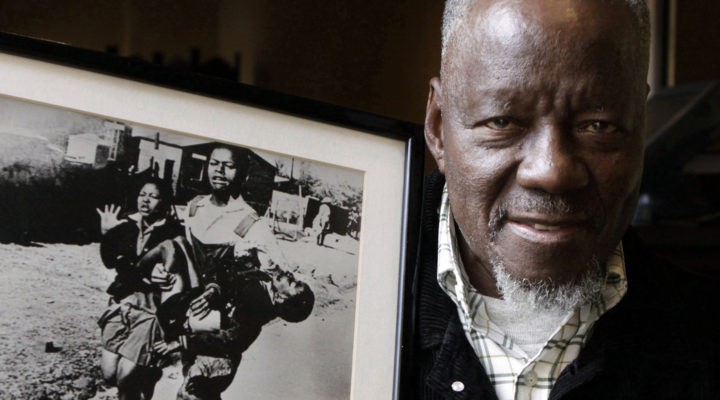

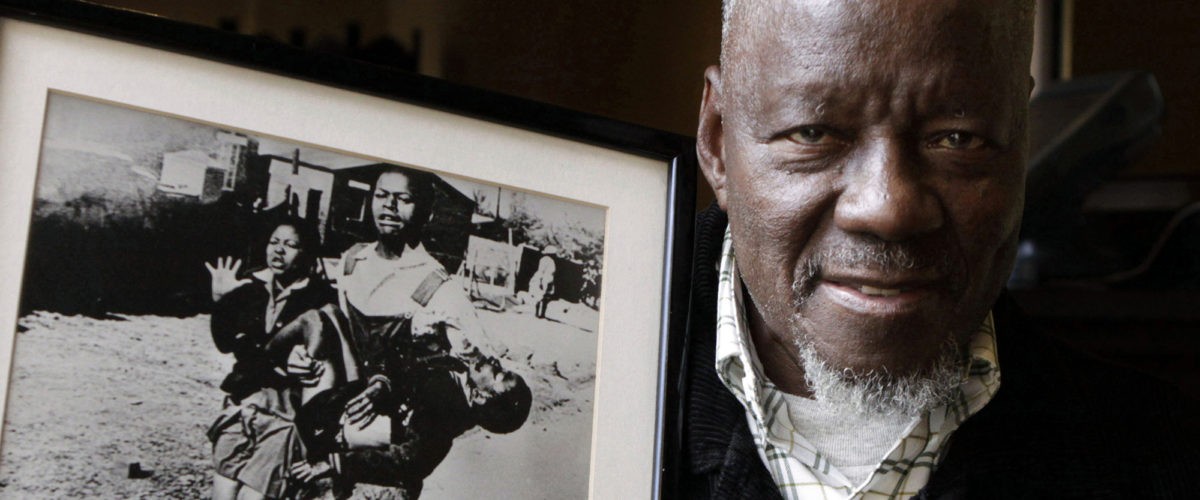

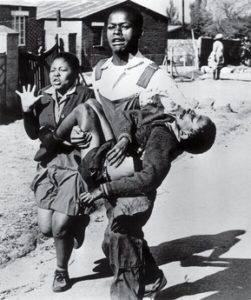

Photo by Sam Nzima/South Photographs via Wikimedia.

Among the dead was Hector Pieterson, a 13-year-old schoolboy, whose photograph — after he was shot and was being carried by a young man, Mbuyisa Makhubua, with Hector’s distraught sister, Antoinette Sithole, striving to keep pace with him — became one of the defining images of not just the incident, but the anti-apartheid struggle in years to come.

In a country already notorious globally for its divisive policies, the Soweto uprising further drew worldwide attention to South Africa’s apartheid system, leading to its eventual demise in the early 1990s and the release from prison of Nelson Mandela, the anti-apartheid freedom fighter, who already had spent 27 years of his life in jail.

In remembrance of the day, South Africa marks June 16 as National Youth Day while the continental body, African Union, commemorates it as International Day of the African Child. The African Union’s recognition of June 16 followed the 1991 adoption of the day by the body then known as the Organization of African Unity.

To mark June 16 this year, the Southern African Catholic Bishops Conference released a message saying South Africa still has a long way to go as a nation where race or skin color doesn’t determine one’s progress in society.

“On the National Youth Day, we reach out to all the young people in the country in a message of solidarity and hope, realizing the burdens that many of you carry,” the statement read, noting, “Our message of hope is also an invitation to imitate the class of 1976 and confront the challenges that we face as a society, including racism, corruption and violence.”

The statement recalled the words of Nelson Mandela: “No one is born hating another because of the color of their skin or their backgrounds or religions. People must learn to hate — and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love, for love comes more naturally to the human heart than its opposite.”

Then it added that racism in South Africa is not something new: “Racism is present in our society because some of us ignore the fundamental truth that we are all equally made in the image of God, sharing a common origin. The ignorance of the truth leads to prejudice and fear of the other, including hatred.”

“How can we profess to be God’s children by only loving those who share our racial and ethnic backgrounds or place of origin?”

The bishops then asked, “How can we profess to be God’s children by only loving those who share our racial and ethnic backgrounds or place of origin? It’s very embarrassing to witness bold expression of racism by groups as well as individuals in our society. We need a genuine conversion of heart, a dialogue that will compel change, and the reform of our institutions (schools, universities, etc.) and society.”

Noting that South Africa “is deeply divided on issues of land, affirmative action and capital ownership,” and that “there are also inequalities in access to quality education and quality health services,” the religious leaders challenged South Africans of all races to do better as a people. “Everyone within society should be part of the ongoing conversion and dialogue, to root out the sin of racism. We should address the causes and the injustices racism produces in order for healing to happen. The healing process will contribute towards ‘building and developing relationships of equality, dignity and mutual respect’ where ‘there is no longer Jew or Gentile, slave or free, male and female.’”

Three decades ago, the Organization of African Unity, as a means to realize its goals for children on the continent, created the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child. The mandate included monitoring and championing the rights of children on the continent, liaising or collaborating with African governments and international organizations on issues pertaining to the rights and welfare of children on the continent. The theme for this year’s International Day of the African Child was ’30 Years After the Adoption of the Charter: Accelerate Implementation of Agenda 2040 for an Africa Fit for Children.’

Three decades ago, the Organization of African Unity, as a means to realize its goals for children on the continent, created the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child.

Despite efforts by African governments to improve the lives of children on the continent however, challenges remain.

A report by Save the Children, a global child welfare agency, states, “Despite progress, research from Save the Children’s 2020 Global Childhood Report shows that sub-Saharan Africa is still home to the 10 worst countries for children, including Niger, Mali, South Sudan and Burkina Faso.

“Across the continent, 152 million children — or one in four — are living in a conflict zone. Nearly 59 million children in Africa suffer from stunting due to malnutrition. Girls in West and Central Africa face the highest risk of child marriage — about four in 10 are married before age 18.”

While the number of out-of-school children in Africa has been embarrassingly high compared with other continents of the world — with Nigeria alone accounting for more than 10 million out-of-school children according to its minister of state for education — the COVID-19 crisis has exacerbated the situation for young students.

A November 2020 UNICEF report noted, “The total number of extreme poor living in sub-Saharan Africa has now likely crossed the 500 million mark, which is approaching close to double the number in 1990 when progress against the Millennium Development Goals started to be measured.”

The region, it noted, “was already a challenging place for many of its 550 million children, but the pandemic has intensified many of the crises they face — and created new ones. About 280 million children — or more than half of the child population — may be dealing with food insecurity. By April 2020, more than 50 million students had lost access to free daily meals, with more than 40 million of those impacted for at least six months and counting.”

On the other hand, “school closures impacted around 250 million students in sub-Saharan Africa, adding to the 100 million out-of-school children before the pandemic. Learning completely stopped for most of them, which has already reduced their lifelong earning potential. Millions are unlikely to ever return to the classroom.”

Anthony Akaeze is a native Nigerian who currently lives in Houston. He is a freelance journalist and covers Africa for BNG.

Related articles:

Beware when ‘law and order’ is cover for lawlessness and disorder | Opinion by Preston Clegg

Be a peace-wager like Nelson Mandela | Opinion by Alan Rudnick

Baptist layman offers lessons from South Africa on overcoming civil war