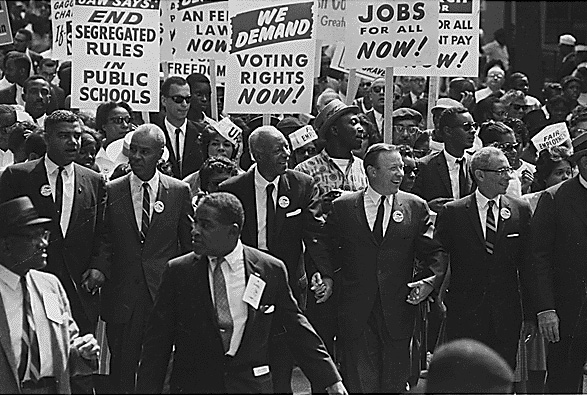

The 1963 March on Washington should be memorialized because it continues to inspire the struggle for democracy, justice and racial equality, said Elijah Zehyoue, co-director of the Alliance of Baptists.

“The march represents a moment when people came together across a multiracial coalition to say we want a better world and a better country for ourselves and our families and our churches,” he explained. “The power is not just remembering what the march did, but in remembering that it gives us the tools for this moment. The march is an invitation for us to work for the transformation of society and the world.”

Elijah Zehyoue

Zehyoue is one of five Baptist leaders interviewed by Baptist News Global about the influence of the Aug. 28, 1963, March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The gathering drew about 250,000 demonstrators to protest the mistreatment of people of color, employment and housing discrimination, and to support the Civil Rights Act then working its way through Congress.

That the assembly was immensely consequential in its time is unquestioned. Covered by national and international media, it landed the Civil Rights movement and its leader, Martin Luther King Jr., solidly in the nation’s social and political consciousness and helped set the stage for King’s 1964 Nobel Peace Prize.

But the march is perhaps most remembered for King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, in which he envisioned an America whose citizens are judged by their character instead of skin color, and in which he lamented that Blacks continued to live in bondage a century after the Emancipation Proclamation.

“One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land. And so, we’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition,” King said from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

“We are still dealing with police violence and an unjust criminal legal system, and the advances brought to us by the Voting Rights Act (of 1965) are being stripped away.”

While the challenges facing marginalized communities in 1963 and 2023 are not identical, they share enough in common to make King’s words relevant in the 21st century, said Zehyoue. “We are still dealing with police violence and an unjust criminal legal system, and the advances brought to us by the Voting Rights Act (of 1965) are being stripped away.”

The courage and vision of King’s remarks also can be useful in responding to recent setbacks in abortion rights and affirmative action, and to the assault on democracy and the LGBTQ and Jewish communities, Zehyoue said. “The example they set in 1963, and the message they shared, speak to the challenges of our time with clarity and vision and inspires people with the hope that things can get better.”

Together with the Civil Rights movement as a whole, the march has informed and inspired the ongoing anti-racism work of the Alliance of Baptists, he said. “As a historically white organization, we have to dismantle historical structures of white supremacy as we do the work of becoming and modeling beloved community.”

Zehyoue added that this weekend’s observance of the 60th anniversary of the march should be taken seriously. “We are still in need of dreams right now. I pray the memorializing will open us up to the possibility of more movement and of more transformation of Baptists participating in the transformation of our world for racial justice and for gender justice for people suffering under oppressive system.”

Emmanuel McCall

Emmanuel L. McCall was the pastor of a small Baptist church on the west end of Louisville, Ky., when the march took place. Unable to attend himself, he and other ministers contributed funds to send a small delegation from local congregations to Washington.

“We knew it would be momentous event and that it would have an enormous impact. But we had no idea how widespread and long-lasting that impact would be.”

“We knew it would be momentous event and that it would have an enormous impact. But we had no idea how widespread and long-lasting that impact would be,” said McCall, former national moderator of the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, a former faculty member at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and adjunct professor at Mercer University’s McAfee School of Theology.

But in 1963, McCall was part of the Progressive National Baptist Convention founded two years earlier and which became King’s denominational home. Supporting the march was another way of showing solidarity with the movement and the denomination, he said.

Emmanuel McCall

“By that time, King already was a very powerful influence, so the idea was to make an impression by drawing worldwide attention to the movement and to Civil Rights and to the convention. It was a matter of keeping that worldwide attention alive.”

The message of the 1963 protest is needed now as much as ever, McCall said. “There’s a retrogression that’s been going on, a reversal of the gains we earned in the ’60s and ’70s. Clearly there are those who regret the gains that were made. And it may be that the media was more convinced about the progress we made than was the average person. Then, when the theme of reparations began to become louder and louder, there was a backlash.”

It doesn’t help that the Black church is not the force it was at the time of the march, he said. “Churches now are struggling after COVID to even stay alive. The pandemic really stuck it to the churches as far participating in activities goes. Fewer people are coming to worship and Sunday school. There is less awareness in the significance of the gospel. A church struggling to exist is also going to struggle in keeping King’s dream alive.”

“A church struggling to exist is also going to struggle in keeping King’s dream alive.”

But McCall said the calling and work of CBF gives him hope that people of faith are standing up to the threats facing the nation.

“CBF is a very active organization, and it has brought about a lot of change,” he said. “It is representative of other movements I see calling for wholeness in society. We are going through a desperate period right now, but I am expecting God to do what God does, which is to use the turmoil in a progressive way.”

Observing and practicing the principles of justice demonstrated during the March on Washington is another way to keep that hope alive, he said. “It gives you something to reach back to and it becomes a way of explaining what still needs to be done.”

Ken Sehested

The church must do its part to keep King’s dream alive, said Ken Sehested, co-pastor of Circle of Mercy Congregation in Asheville, N.C., and founding director of the Baptist Peace Fellowship of North America.

“It clearly needs a prominent place in our liturgical calendars,” he said. “It was such a mammoth success, bigger and more joyful than and hopeful than anyone could have imagined. And we need to continue to instruct our young, to introduce them to that dream.”

“‘I Have a Dream’ has become a salve to console folk who don’t want to remember the hard times we have had.”

But the vision of the march, and of the wider Civil Rights movement, is often used by those who are opposed to social and racial justice and to label various equality movements as discriminatory, Sehested said. “It becomes a convenient excuse for opting out of the struggle that is nowhere near to being finished to make up for the inequality that still haunts us and disables us. ‘I Have a Dream’ has become a salve to console folk who don’t want to remember the hard times we have had and the brutal treatment we have visited on the people from another shore.”

Ken Sehested

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis invoked the speech in his 2021 introduction of the Stop Woke Act, which banned Critical Race Theory and the teaching of race and LGBTQ issues in public schools. The measure was passed the following year.

“You think of what MLK stood for. He said he didn’t want people judged on the color of their skin, but on the content of their character,” DeSantis said, adding that the woke movement wants to pit race against race. “It puts race as the most important thing. I want content of character to be the most important thing.”

It’s at best a deranged interpretation of King, Sehested said. “Where there is a delusion in people’s memory about that march are things like anti-wokeness, the claim to be colorblind or the rationale for undermining the most minimal standards of affirmative action. These are all a convoluted use of the ‘I Have a Dream” moment in American history. They are based on the assumption that we have done our due diligence already, that all the repentance that needs to happen has already happened.”

The success of the march in gaining momentum for civil rights victories often overshadows the challenges King faced later as the movement continued, including his 1968 condemnation of the Vietnam War, Sehested said. “His favorability rating at that time slipped to something like 33%. It was almost a death blow to his reputation. Even his allies in the Black community and in white liberal community turned on him fiercely when he offered a frontal condemnation of the war in Vietnam.”

Mahan Siler

The continuing influence of the march and King’s speech cannot be fully appreciated without understanding those later difficulties, said Mahan Siler, former pastor of Pullen Memorial Baptist Church, in Raleigh, N.C., and of Ravensworth Baptist Church in Washington, D.C.

“You can’t understand King’s great speech without knowing the rest of the story and how his view of justice shifted as his own understanding grew,” Siler said.

Mahan Siler

Siler was the pastor at Ravensworth when King was assassinated in 1968 and recalled working with Black pastors to quell flaring tempers and riots.

“In that moment, I was inspired by King and his view of nonviolence. And of course, I was immensely moved by ‘I Have a Dream’ and also with the successful legislation in 1964 (Civil Rights Act) and 1965 (Voting Rights Act). All of these things had given me such a great hope about racial justice.”

Wendell Griffen

The march also was inspirational for Wendell Griffen, a retired Arkansas judge and pastor of New Millennium Baptist Church in Little Rock. “I wasn’t there, but my moral, social, spiritual and political outlook was influenced by people who were key figures in the Civil Rights movement that was the focus of the march 60 years ago,” he explained.

King was just one of the many Civil Rights activists and march organizers who captured his imagination, Griffen said. Others included A. Phillip Randolph, Dorothy Height, Roy Wilkins, Whitney Young and Gardner Taylor.

Wendell Griffen

“They were champions in my 11-year-old mind. Along with Medgar Evers, they showed the courage, wit, determination and moral fortitude to challenge racial and economic injustice in the U.S. They refused to be silent about it, rejected appeals by the Kennedy administration that the march be canceled, and left the march determined to continue and intensify their fight for jobs and justice.”

Conspicuously absent at the time of the march was the white Southern church, he said. “That was also true for the Chamber of Commerce, the major national political parties and the white educational and professional groups.”

Even so, the march was the catalyst for later social justice efforts including the Million Man March, Occupy Wallstreet, #MeToo, Black Lives Matter and LGBTQ rights movements, Griffen said. “Each of these movements and initiatives has a connection to the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

“Sixty years later, the fight continues.”

Note: Anniversary events are planned in Washington, D.C., this weekend, and BNG will provide coverage of those early next week.

Related articles:

The untold story of Black women leaders in the Civil Rights Movement | Opinion by Marvin McMickle

Three reasons 2021 looks like 1961 in voter suppression | Opinion by Bill Leonard

MLK’s civil rights work was an outgrowth of his Baptist tradition, author explains