In August 2013, I was serving as a pastor on the outskirts of Washington, D.C. All month long, there was a feeling of excitement in the air. That Aug. 28 marked the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington, the march we remember as the high tide of the Civil Rights movement, and a grand week-long celebration was planned. Stars and dignitaries from around the world came to town to rightfully celebrate a seismic event in the advance of justice and freedom.

Not all was well, of course. America remained a troubled nation. A month before the anniversary celebrations, vigilante George Zimmermann was acquitted of the 2012 murder of Trayvon Martin. A month before that, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down key protections of the Voting Rights Act, one of the landmark victories the 1963 march helped to achieve.

Todd Thomason

Even still, I remember a sense of optimism permeating the 50th anniversary. America’s first Black president had won re-election to a second term. The Great Recession was receding. Despite our troubles and the hard work still needed to realize it, Dr. King’s dream seemed well within reach.

Then police strangled Eric Garner. Then they shot and killed Michael Brown. Then Tamir Rice. Then all the officers involved were acquitted, if they were charged or reprimanded at all.

And as these summary police executions of unarmed Black men continued in plain public view, America chose the birther-in-chief, Donald Trump, as President Obama’s successor. Rhetoric coarsened, violence escalated, dog whistles proliferated. White Christian nationalism emerged from the fringe emboldened, culminating in the January 6 insurrection.

Now the Supreme Court has voided the right to an abortion and swept aside affirmative action, too. Manufactured hysteria over “Critical Race Theory” abounds. School boards are banning “woke” books, redacting Black history and whitewashing school curricula. States are making voting processes narrower and more rigid, thus making it harder for minorities and low-wage workers to let their voices be heard. Many public schools remain practically, if not legally, segregated.

All the while, the wealth gap between white America and Black America has widened. Black life expectancy continues to be significantly lower, and Black student debt remains substantially higher than that of their white counterparts.

“Many days, justice barely seems to trickle, much less roll.”

Ten years on, the mood surrounding the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington feels very different. Many days, justice barely seems to trickle, much less roll. Four federal and state indictments totaling 91 felony charges have yet to slow the ideological sedan chair carrying Donald Trump toward the 2024 Republican nomination. And the most enthusiastic shoulders bearing him along continue to be those of white evangelical Christians, folk who should know better since they claim to know Jesus.

(123rf.com)

A fading memory

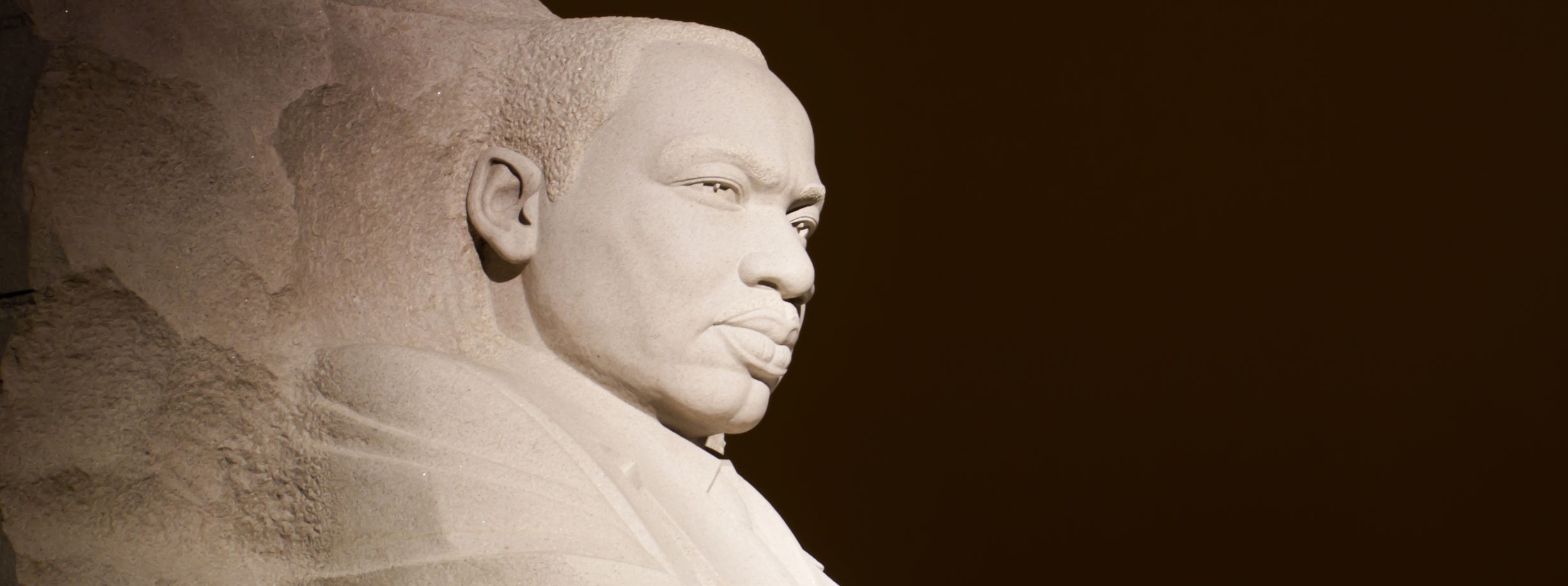

In every village and every hamlet, in every state and every city across America, much of the fruit of the Civil Rights movement looks to be rotting on the ground. On the National Mall, King appears encased in carbonite rather than enshrined in marble. His dream, his prophetic vision for a better, truer America, if not broken, feels like it’s fading from our collective conscience.

There is good reason, then, that organizers billed the 60th anniversary observance as a continuation of the 1963 March rather than as a celebration of it. King’s family, Al Sharpton and other present-day civil rights leaders are determined to remind us of what a persistent, united coalition of people can accomplish in the face of vehement opposition. Even if broad enthusiasm for the event is hard to muster in the face of so many recent setbacks. Even if the victories of the past seem far distant indeed.

“The inclination to keep marching is right.”

The crowd that gathered on the National Mall this past weekend was a mere shadow of the throng that descended on Washington in 1963. But the inclination to keep marching is right.

Anyone who believes America can become all our founding documents declare it to be must march on and keep marching until what we see around us resembles what we read on paper.

Underwhelming as it may seem, then, the 60th anniversary continuation should serve as a much-needed wakeup call for us to shake off our apathy and our disillusionment and get back to work. We’re going to have to carry the torch more intentionally, personally and persistently than we’ve become accustomed to if we are to drive back this present darkness.

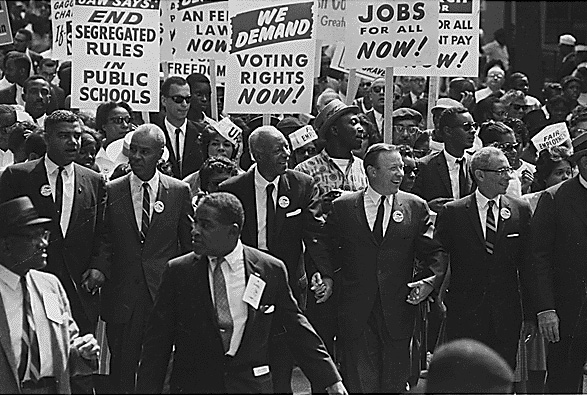

From the 1963 civil rights march on Washington. (Photo/Wikipedia)

A new march for new times

Of primary importance will be resisting the temptation to dismiss the 60th anniversary continuation as a failure if it doesn’t make headlines, if it doesn’t bear obvious fruit. The reason is twofold.

The first reason is that no march is ever intended to be sufficient. A demonstration is always a means to an end. A march is never about the march; it’s about the cause and rallying people to the cause so that the next march is larger and louder.

The second reason constitutes one of the hard, sober truths we must confront concerning how the socio-political landscape of 2023 differs from the landscape of 1963. Over the course of 60 years, mass demonstrations have lost their mojo on the national stage. That doesn’t mean they’re obsolete. Marches are cathartic for the marchers, and they still can have an impact; but that impact has been shown to be more effective when coming from multiple localdemonstrations, such as we witnessed in response to the police murder of George Floyd, rather than from a larger, centralized spectacle.

Even if turnout for the 60th anniversary continuation had tripled the attendance of the original March on Washington, it still would achieve less than a third of the result. No one in Congress will feel pressured to change their pre-march position on any issue. That is because, in the wake of the 1960s Civil Rights movement, the powers-that-be have learned. They’ve adapted. They’ve taken measures to insulate themselves from thunderous projections of the people’s collective voice.

“They’ve so gerrymandered and jerry-rigged the system that they do not have to care or even pay attention to what happens on the Mall in Washington.”

Over the course of decades, they’ve so gerrymandered and jerry-rigged the system that they do not have to care or even pay attention to what happens on the Mall in Washington. They only have to listen to a small subset of voters and donors within the districts they represent. And for those politicians who have worked to retake the ground the Civil Rights movement gained, that select pool of voters wouldn’t have been watching, much less participating in, this 2023 march. They’d have been tuning in to the rant du jour on conservative talk radio and right-wing cable news.

That reality reflects a second hard, sober truth of our present situation: Mass demonstrations need mass media to exert leverage. Nonviolent civil disobedience moved the needle of public opinion in the 1960s because photos of firehoses battering, SWAT batons bludgeoning and police dogs mauling unarmed, peaceful protesters made the front page of local papers. Images of people flooding the National Mall filled the national evening news. The inspiring, prophetic words of King echoed through the nation’s living rooms. The movement changed people’s minds by getting into their hearts through their eyes and ears.

In 2023, there is no such thing as national evening news. We all live in niche media bubbles. Many Americans, especially those of a certain political ideology, won’t even know an anniversary march to continue the unfinished work of the 1960s has taken place. Just like they don’t know the extent of the indictments against Donald Trump or the evidence behind them. Anything to do with social justice is anathema in those spheres.

None of this means that we, the people are helpless. It simply means we cannot fight 21st century social battles solely relying on 20t century examples and tools. Or, at least, what we think of as the 20th century’s examples and tools.

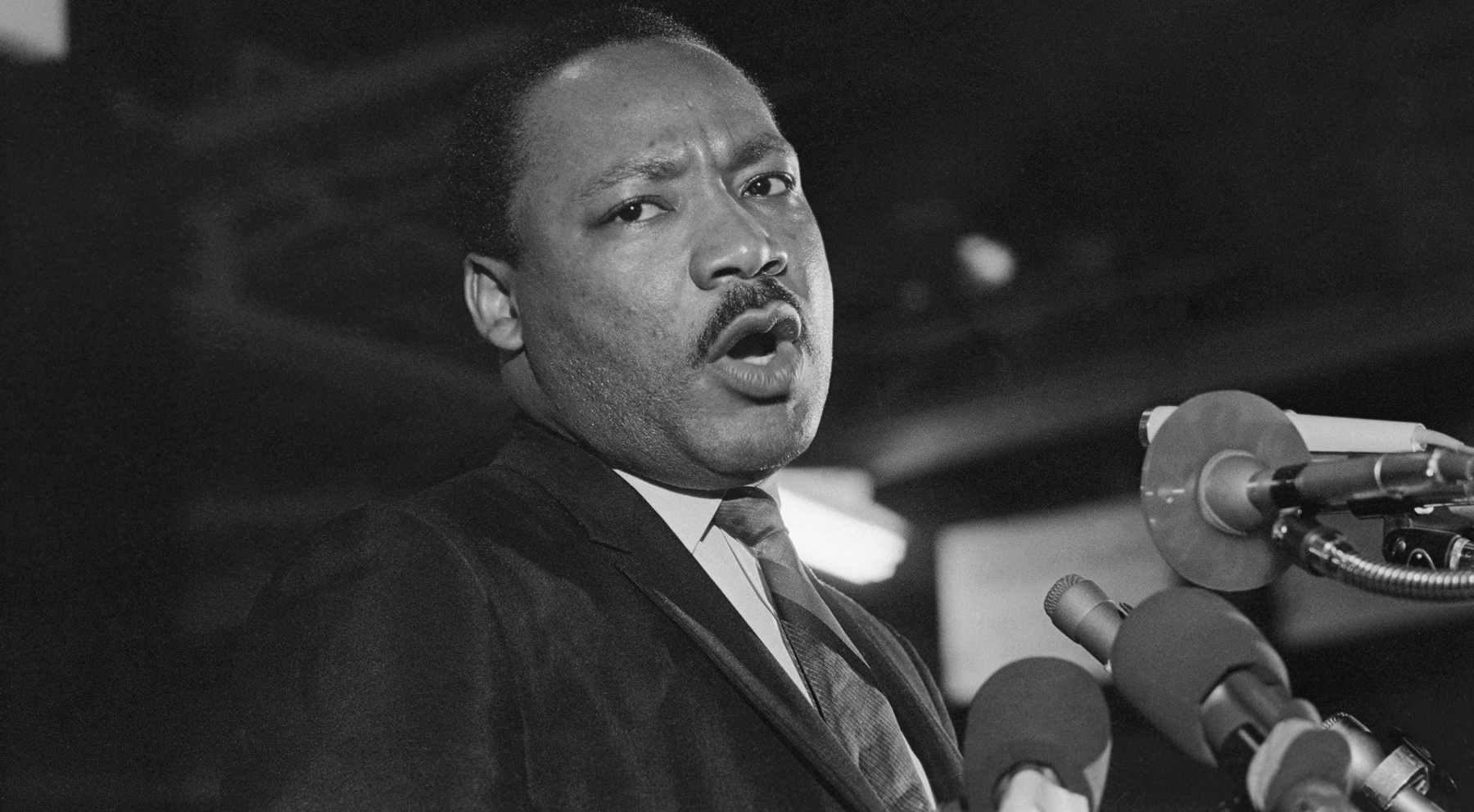

Martin Luther King addresses 2,000 people on the eve of his death in Memphis. (Getty Images)

MLK still inspires

If we look closely, if we read and study the history so many school boards don’t want our children to study, we will see the Civil Rights movement was fought with a more sophisticated and manifold toolkit than we generally remember (or have been taught); yet the core of it was really quite simple and straightforward. Sixty years after the March on Washington, 55 years after his assassination, Martin Luther King can still inspire us and point us in the right direction.

To allow him to do that, however, we must familiarize ourselves with more than “I Have a Dream.” King’s most important speech was his last, delivered on the night before he was shot and killed in Memphis. It is a reflective as well as prophetic address. He understands and accepts how things are likely to end for him. And so, he spends time toward the end of this speech exhorting, encouraging and preparing the crowd to carry on the work, to carry on the fight, with or without him. Significantly, he grounds the way forward in the Parable of the Good Samaritan.

Now, let me say as I move to my conclusion that we’ve got to give ourselves to this struggle until the end. Nothing would be more tragic than to stop at this point, in Memphis. We’ve got to see it through. And when we have our march, you need to be there. Be concerned about your brother. You may not be on strike. But either we go up together, or we go down together.

Let us develop a kind of dangerous unselfishness. One day a man came to Jesus; and he wanted to raise some questions about some vital matters in life. At points, he wanted to trick Jesus, and show him that he knew a little more than Jesus knew, and through this, throw him off base. Now that question could have easily ended up in a philosophical and theological debate. But Jesus immediately pulled that question from mid-air and placed it on a dangerous curve between Jerusalem and Jericho. And he talked about a certain man, who fell among thieves. You remember that a Levite and a priest passed by on the other side. They didn’t stop to help him. And finally a man of another race came by. He got down from his beast, decided not to be compassionate by proxy. But with him, administering first aid, and helped the man in need. Jesus ended up saying, this was the good man, this was the great man, because he had the capacity to project the “I” into the “thou,” and to be concerned about his brother.

Now you know, we use our imagination a great deal to try to determine why the priest and the Levite didn’t stop. … But I’m going to tell you what my imagination tells me. It’s possible that these men were afraid. You see, the Jericho Road is a dangerous road. I remember when Mrs. King and I were first in Jerusalem. We rented a car and drove from Jerusalem down to Jericho. And as soon as we got on that road, I said to my wife, “I can see why Jesus used this as a setting for his parable.” It’s a winding, meandering road. It’s really conducive for ambushing. You start out in Jerusalem, which is about … 1,200 feet above sea level. And by the time you get down to Jericho, 15 or 20 minutes later, you’re about 2,200 feet below sea level. That’s a dangerous road. In the days of Jesus it came to be known as the “Bloody Pass.” And you know, it’s possible that the priest and the Levite looked over that man on the ground and wondered if the robbers were still around. Or it’s possible that they felt that the man on the ground was merely faking. And he was acting like he had been robbed and hurt, in order to seize them over there, lure them there for quick and easy seizure. And so the first question that the Levite asked was, “If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?” But then the Good Samaritan came by. And he reversed the question: “If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?”

That’s the question before you tonight. Not, “If I stop to help the sanitation workers, what will happen to all of the hours that I usually spend in my office every day and every week as a pastor?” The question is not, “If I stop to help this man in need, what will happen to me?” “If I do not stop to help the sanitation workers, what will happen to them?” That’s the question.

Let us rise up tonight with a greater readiness. Let us stand with a greater determination. And let us move on in these powerful days, these days of challenge to make America what it ought to be.

The key question

That’s the core of it. A single question. The question that was before the crowd that April night in Memphis in 1968, the same question that is before us today in 2023.

If you, if I, if we do not actively join the fight for freedom and justice; if we do not aid and protect those who have fallen prey to the social, political and economic ditches of this life; if we do not live for something greater than our own preferences and advantage, the question isn’t, “What will happen to us?” The question is, “What will happen to them?”

“It’s simply a call to live where we are in a different way.”

That is the question that holds the key to a better future. That is the question that shows us the way forward. It’s not a call to lead a march, to organize a boycott, to be a saint, to be a martyr, to be the next Dr. King. It’s simply a call to live where we are in a different way, in a better way, in different and better relationship with our neighbors, which is something any and all of us can choose to do. Or not.

It is precisely that simple, straightforward choice that propelled the Civil Rights movement forward from the very beginning, from its start in Montgomery, Ala. — something we too often overlook, or something we’ve forgotten. By lionizing King, Ralph Abernathy, John Lewis, Rosa Parks and other heroes of the national stage whose courage, leadership and witness rightly deserve praise and recognition, we have inadvertently obscured the tens of thousands of other souls who never took the stage but whose work and dedication were essential for the success of the movement. In fact, without them, there would not have been a movement.

These were the maids, the janitors, the cafeteria workers, the factory workers and the other ordinary folk who chose to boycott segregated buses in Montgomery.

The ones who chose to walk, even if it meant walking many miles in unfavourable weather.

The ones who didn’t stop riding for a day or two to make a point.

The ones who stopped riding the bus for as many days as it took to change the system.

These were also the car owners who offered lifts, the taxi drivers who charged reduced fares for those who were walking — to help ease their burden as the boycott stretched into weeks and then into months. Together, they kept on walking, then they started marching.

Those — those are the true hands, feet and faces of what we know as the Civil Rights movement. Those are the hands, the feet and the faces that accomplished what we honor and celebrate from 60 years ago. And those are the same hands, feet and faces that are still among us, that will accomplish what our children and grandchildren will celebrate and honor 60 years from now. Or not.

‘Go and do likewise’

On this 60th anniversary of the March on Washington, we have a choice. We can shrink. We can despair. We can allow our representatives to continue to ignore the people they’re supposed to serve. Or we can shake off the apathy of our slumber and start developing a kind of dangerous unselfishness, letting the Good Samaritan serve as our example. That isn’t just King’s advice. That’s straight from the mouth of Jesus: “Go and do likewise.”

“Before justice can roll, the sleepers must awake.”

Before justice can roll, the sleepers must awake. So, educate yourself. Read the books the powers-that-be don’t want you to read. Find ways to build relationships with those who don’t look like you, don’t sound like you, who aren’t oriented like you, and listen to their stories. Listen to their experiences. Commit to living more like the Good Samaritan in your community, striving to love your neighbor as yourself: not just wanting them to have the same things, the same opportunities that you desire for you and yours, but working to ensure they have access to those things, those opportunities, just as you do for you and yours.

If you don’t know where else to start, start in the voting booth. Your vote is a powerful thing. That’s why the Civil Rights freedom fighters fought so hard to secure it, and why so many politicians have worked so hard to limit it.

Because the powers-that-be have been so successful insulating themselves from the voices of so many people in recent years, there may be more immediate and specific ways to love your neighbor as yourself, but there is no more tangible way than to enter the voting booth with the same spirit in which the Good Samaritan set out on his journey — with the well-being of those in life’s ditches in mind.

Truth be told, if we vote on a Tuesday only according to our own personal preferences, only according to our own self-interest, we don’t vote any differently than the bigots, the chauvinists, the white supremacists, the narcissists and the sociopaths — no matter how enthusiastically we worship Jesus on a Sunday. Ultimately, voting will be the way we un-jerry-rig the system.

In these days of challenge, may we rise up with a greater readiness and stand with a greater determination. Change is possible. We’ve seen it happen. Like those who have marched before us, we just have to reverse the question, to project the “I” into the “thou,” and decide to care for one another. Change will flow from there.

Or not.

Todd Thomason is a gospel minister and justice advocate who has served as pastor of churches in Virginia, Maryland and Canada. He holds a doctor of ministry degree from Candler School of Theology at Emory University and a master of divinity degree from McAfee School of Theology at Mercer University. In addition to Baptist News Global, Todd writes regularly at viaexmachina.com. Follow him on Twitter @btoddthomason and Facebook @viaexmachina.

Related articles:

5 ministers reflect on the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington

Author of new MLK biography explains the logistical miracle of the March on Washington

The untold story of Black women leaders in the Civil Rights Movement | Opinion by Marvin McMickle

Three reasons 2021 looks like 1961 in voter suppression | Opinion by Bill Leonard

MLK’s civil rights work was an outgrowth of his Baptist tradition, author explains