I grew up in a family that worshipped the trinity: God, the Southern Baptist Convention and the Dallas Cowboys.

I was born in Fort Worth, Texas, while my father was a student at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary. By the time I started first grade back in East Tennessee, autumn sabbaths consisted of First Baptist Church, Sunday dinner, the Dallas Cowboys and Church Part Two. Those Sunday evening services preempted my getting to watch The Wonderful World of Disney — except when I managed to be sick enough to miss church but not too sick to watch TV.

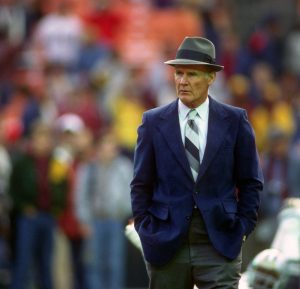

Tom Landry (Photo by George Gojkovich/Getty Images)

Missing Disney was just an irritation, though. My first spiritual crisis happened when Jerry Jones bought the Dallas Cowboys and fired coach Tom Landry. One of my Spire Christian Comics was Coach Landry’s biography. He was a Word War II veteran who flew 30 combat missions, saving his crew more than once. His demeanor made him my icon of being a Christian gentleman. After my hero’s firing, I renounced my faith in the Cowboys organization, leaving me with just two aspects of the divine: God and the Southern Baptist Convention.

A good Southern Baptist lad

I strived to be a good Southern Baptist lad. I can still say the boy-missionary pledge. “As a Royal Ambassador I will do my best to become a well-informed, responsible follower of Christ; to have a Christ-like concern for all people; to learn how the message of Christ is carried around the world, and to keep myself clean and healthy in mind and body.”

“The more I read about the Crusades, the more horrified I was that my denomination had used crusaders as role models for boys.”

My final year at Royal Ambassador camp, I was the Bible baseball home run king. Our version of the trivia game included questions on the officers of the Tennessee Baptist Convention. Eventually, I would come to be repulsed by a boys’ program modeled after the Crusades. At the time, however, I was determined to ascend the ranks from page, to squire, to knight. Only in seminary would I become appalled when I read of Christian crusaders trying to see how many Muslim children they could get on a lance. The more I read about the Crusades, the more horrified I was that my denomination had used crusaders as role models for boys.

Still, at the time, I was a good soldier. Then I heard rumblings in the ranks.

Rumblings of conflict

It started with listening to my paternal grandmother and her best friend fretting about goings on at the Southern Baptist Convention. Then, being a bit of a nerd — OK, a lot of a nerd — I picked up on tension being reported in our state Baptist paper. One day in the early 1980s, I asked my dad what was going on in The Convention. I don’t remember his exact words. I just remember his raised eyebrows as he explained about two sides’ struggle for power.

Phil Donahue on his daytime TV talk show

A few years later, the growing descension in the SBC was on an episode of TV talk show Donahue. According to a search I just did, it was June 21, 1985. That means I had just finished my freshman year in college, and I likely was watching TV because I was couch-ridden with a very serious case of mononucleosis.

I was an emaciated 6’ 2”, 135-pound 19-year-old who looked and felt like a little boy as I watched the talk show. Phil Donahue hosted two Southern Baptists to discuss the rising conflict in the SBC. One guest was a kindly, silver-haired, avuncular man who struck me as tender and Christlike. The other guest had his eyebrows knitted most of the time and seemed to speak harshly to the kindly older man. In general, he just seemed a bit gruff. I labeled him “Grumpy Man.”

That was in the eyes of 19-year-old me who was physically and emotionally more like a 15-year-old. For the most part, I was still an impressionable child. On the surface, I saw a smiling man I wanted to emulate and a grumpy man whose tone I rejected. This perspective received affirmation from one of my pastors when I mentioned my reaction, and he said, “That negative attitude is what has pushed me to the (side of conservatives).”

With the benefit of hindsight, it wasn’t much of a push for him at all. The negative attitude of progressives was a convenient whipping boy for someone who spent much of a homecoming sermon railing against homosexuality in a way that made no sense at our small church. Still, his statement about harsh progressives influenced my perception for years.

Meet our panelists

Photo from Paul Pressler papers, Archives and Special Collections, Library at Southeastern, Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, Wake Forest, NC.

The avuncular man who had made the positive impression on me was, I would later learn, Judge Paul Pressler. Judge Pressler is attributed with being one of the two architects of what has come to be known — depending on one’s perspective — as either “the conservative resurgence” or “the fundamentalist takeover” of the SBC. Supposedly he was teaching college Sunday school in Texas and became concerned over what he saw as liberal things his pupils reported being taught at Baylor University. He helped concoct a plan to exploit Southern Baptist policies to gain control of the various Southern Baptist governing bodies. I saw him as a nice man. He must surely be filled with the fruits of the Spirit.

Four years later, I had under my belt a Baptist college education and a year of saving money for seminary. After spending most of my savings on a mission trip to the Philippines, I was off to Louisville, Ky., to study at Southern Baptist’s oldest seminary. My second Sunday there, I attended Walnut Street Baptist Church, a large urban church I had been directed to by a college classmate who grew up in Louisville.

“I immediately recognized him as ‘Grumpy Man’ from the Donahue show.”

When the pastor, Ken Chafin, walked onto the platform, I immediately recognized him as “Grumpy Man” from the Donahue show. Come to find out, he did have an edge to him. He was the only person I ever saw scold a child during a children’s sermon. Yet, I also discovered his gentle and playful side — not to mention his scholarly acumen and notoriety. He had served as the Billy Graham chair of evangelism and preaching professor at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary.

The other side of Ken Chafin

At a welcome event for new students, he described the kinds of challenges we would face. I became indignant when he said, “You will meet people whose necks are red.” In the context, I heard him insulting conservatives — like my family. I set up an appointment to share my feelings. We had a wonderful conversation. I saw his face glowing kindly like I had seen Paul Pressler’s face on Donahue. One man was harsh in public when confronting what he saw as a threat to the fabric of faith, but he was very gentle and attentive in private. The other man was publicly ingratiating, but serious accusations have been made about alleged private machinations that led to him paying $450,000 to settle a case of sexual assault against a male.

“One man was harsh in public when confronting what he saw as a threat to the fabric of faith, but he was very gentle and attentive in private.”

In terms of the righteously indignant Ken Chafin, at that welcome event for new seminary students, I saw a wonderful contrast to my initial impression. He told a story about his own seminary days: “In preaching class, we were told to bring a manuscript of our best sermon. As a young preacher, I thought my best sermon was whichever one I had preached most recently. So, I submitted a manuscript of my most recent sermon. I got it back with a grade of ‘C’ marked on the paper. I went to the professor and said, ‘I don’t understand why I got a C. When I delivered this sermon, five people came forward and made decisions.’”

Ken Chafin

Chafin grinned. “My professor said, ‘Imagine what would have happened if it had been a good sermon.’” The roomful of seminary students exploded in laughter. I was struck by the humility of the man — a seminary preaching professor who shared about getting a C on a sermon.

Thus, in the twists and turns of life, “Grumpy Man” became my beloved pastor, and the football team that once brought me such joy now only evokes pleasure when I see their owner bitterly losing. (Note to self: Work on this grudge issue, dude. I mean, according to an article you just found, even Tom Landry let go of his bitterness and went to a ceremony in his honor at Cowboys’ stadium, where his name was added to the Ring of Honor. This isn’t working. I know professional football is a business, but Tom Landry deserved better. Go, Titans.)

If business and politics are dirty in the secular world, it is no longer surprising but deeply saddening they are just as or even more dirty in church settings. Sometime in the late 1990s, a prominent moderate pastor, affiliated with the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, invited me and another young minister to breakfast. He was recruiting us to help him keep conservatives out of power in the Tennessee Baptist Convention. I don’t remember the details of the plan. I do remember the other young minister and I standing out in the parking lot and agreeing that while we loved the man who invited us to Cracker Barrel, we wanted no part of backroom plotting to homogenize positions of power.

Two aspects of conflict

Family therapists talk about the two aspects of conflict: content and process. Content is the subject of the argument — the what. Process is how the argument is conducted. For instance, one spouse in Couple A says, “You idiot. I was late for work again today because you didn’t take out the trash.” In Couple B, one of the spouses says, “Hey, Hon, my understanding was that you were going to be responsible for the trash, and I was going to handle picking up the dry cleaning. I’ve been late twice now because the trash wasn’t taken out. I would appreciate your help working this out.” In both cases the content is the same: the trash not being taken out. Clearly, though, the process — or the how — of this argument is much different in these couples.

When I was in seminary, I caused an awkward moment at a dinner party. The host had written an article for an underground campus newspaper. He asked what we thought of the article. I took issue with him using the term “fundies” to refer to the conservative wing of the SBC. He questioned my objection. I replied, “The first thing we do in war is label the enemy with a disparaging epithet. In World War II, Germans were called krauts. In Vietnam, our GIs called the enemy gooks. Such names are intended to dehumanize, because it’s easier to kill a kraut or a gook than a human being. It doesn’t serve the church to dehumanize our opponents by calling them names.”

While dehumanizing labels are inappropriate, sometimes one party in a disagreement can be labeled “wrong” about the content of the argument. The earth is not flat. Those who say it is flat are categorically incorrect. If flat-earthers refuse to look at the evidence, they and the round-earthers reach a point of wasting their time. When folks can’t bend about the content, no amount of positive process can fully resolve the issue. However, lack of agreement in content does not justify unhealthy process.

Researcher John Gottman has described negative process as the difference between toxic criticism and constructive complaint. Criticism is more likely to trigger defensiveness, and criticism and defensiveness are two of his “four horsemen of the marital apocalypse.” (Yes, a Jewish researcher used Christian imagery to illustrate his concepts.) The other two horsemen are withdrawal and contempt. Observing these four behaviors in videos of couples’ arguments led Gottman to be 97% accurate in predicting whether couples who did not get intervention subsequently got divorced.

If Gottman had looked at the 1970s Southern Baptist Convention as a marriage, he certainly would have seen criticism, defensiveness, withdrawal and contempt.

“Eventually, I came to see that smiles can be deceptive and anger may be a healthy reaction.”

Since he was talking to an individual and not an unseen group of sinners, I saw Ken Chafin’s anger as a sign the other side was more Christlike. Eventually, I came to see that smiles can be deceptive and anger may be a healthy reaction. However, if our anger is warranted, we still have to be careful how we express it, especially when the audience may consist of those not equipped to digest anger.

In his TED Talk reporting the findings of Harvard’s decades-long study of happiness, Robert Waldinger said having lots of relationships is not enough to combat the toxic effects of loneliness; rather it is the quality of relationships that promotes health. He said, “It turns out that living in the midst of conflict is really bad for our health. High-conflict marriages, for example, without much affection, turn out to be very bad for our health, perhaps worse than divorce.”

Multiply by dividing

It has been said that Christianity multiplies by dividing. For the longest time, I hoped Southern Baptist fundamentalists and progressives would be able to reconcile. But that’s like asking a scuba diver and a mountain climber to carry out a desert expedition. It can be done, but it will be messy and not make the most of their resources. Some things stop being healthy, and folks have to go different directions.

Southern Baptist progressives and conservatives divorced. Now Methodists are splitting over the issue of gay clergy, and this divorce is happening in part because of the ironic result of a conservative voting bloc in Africa that was ushered into the denomination by progressives.

On one level, the latest divorce in Baptist life has been sad. It certainly was painful to grow up in the crossfire between my ideological parents. For the respective groups, it has been costly both financially and spiritually. However, it has afforded the opportunity for growth in those no longer weighted by conflict.

For one thing, a wide variety of congregations help meet the needs of a diverse world. In addition, in those cases where flat-earthers and round-earthers can’t agree on curriculum, going separate ways allows adherents to invest their resources without the sense of supporting something they find unconscionable. In the tragic but too-often appropriate words of Willie Nelson: “The reason divorces are so expensive is, they’re worth it.”

That feels cynical. However, there likely is some truth to that glib wisecrack. When we divorce ourselves from toxic devotion to football teams and denominations (and political parties, carbohydrates, et cetera ad nauseum), we might just find ourselves left with God alone.

Brad Bull

Brad Bull is a licensed marriage and family therapist in Tennessee. He also has served as a hospital chaplain, youth minister, UPS driver helper and college professor.