If you haven’t heard about the 1925 Scopes trial in Dayton, Tenn., that is about to change.

We are rapidly approaching the centennial of that messy affair, and books and articles on the subject already are starting to appear. Any discussion of American Christianity must pass through the sleepy Tennessee town where William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow went toe-to-toe.

The tensions on display in Dayton have not left us. In fact, they have dogged me my entire life.

It began when Mr. Wilson, a gruff middled-aged man with a crew cut, held aloft a little pamphlet.

“Some of you may find this little thing in the back of your text books,” he said with a hint of sarcasm. “You can read it, or you can throw it in the trash. It doesn’t matter because I won’t be talking about it.”

Suddenly curious, I looked in the back of my book. There it was.

At some point, the Alberta Legislature had stipulated that the theory of evolution couldn’t be taught in the province of Alberta unless creation science was presented as an alternative. Between 1935 and 1971, the Social Credit Party dominated Alberta politics and, as the creationist supplement to my textbook suggests, premillennial fundamentalism was part of the mix.

Premier Tommy Douglas, 1953 (Saskatchewan Archives Board)

I was amazed, and a bit alarmed, when I read that the pamphlet had been written by Louis Mix, my parents’ Sunday school teacher.

The politics of Saskatchewan, the Canadian province to the east of Alberta, was controlled by a very different religious vision during the middle decades of the 20th century. In 1925, while American eyes were glued on Dayton, Tenn., Tommy Douglas, the young pastor of Calvary Baptist Church in Weyburn, Saskatchewan, studied at Brandon College in Manitoba, a hotbed of Social Gospel fervor. Douglas was deeply influenced by Harris MacNeill, a product of the University of Chicago who had studied with Shailer Mathews, the primary architect of “modernist” theology.

After spending a year as my father’s pastor and Sunday school teacher in Weyburn, Saskatchewan, Douglas spent a summer at the University of Chicago. When Douglas was sent to Chicago’s “hobo jungle” to gather statistical information for a sociology class, he was appalled by the misery he witnessed. When the young Baptist pastor returned to my father’s church, he was looking for alternatives to free market capitalism.

After a few eventful years in Depression-era Weyburn, Douglas abandoned pastoral ministry for politics, eventually becoming Saskatchewan’s first socialist premier. Known as “the father of Canadian Medicare, Douglas would eventually be voted the greatest Canadian of the Twentieth Century.

For my father, theology was a wrestling match between the Social Gospel theology of his childhood mentor and the fundamentalism of the man who wrote the creationist supplement to my high school biology textbook.

Fifty-six years later, nothing much has changed.

The modernism of Shailer Mathews

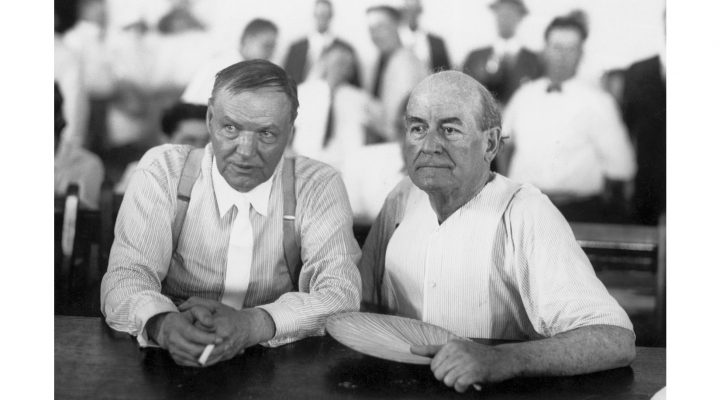

So many sweating people crowded inside the Dayton courthouse in the summer of 1925 that the presiding judge feared the floor would give way. At the front of the room, Clarence Darrow, the celebrity defense attorney, was flanked by a cadre of Harvard biologists and modernist theology professors. Darrow and the American Civil Liberties Union were hoping the judge would allow these men to serve as expert witnesses.

Shailer Mathews

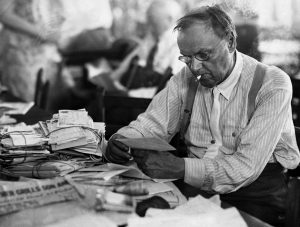

At the head of the list was Shailer Mathews, dean of the University of Chicago Divinity School. Mathews also headed up the Department of Religion at the Chautauqua Institution and had served as president of both the Northern Baptist Convention and the Federal Council of Churches.

Mathews preferred to call himself a “modernist” rather than a liberal. Modernism, he explained a year before the Scopes trial, “is the use of the methods of modern science to find, state and use the permanent and central values of inherited orthodoxy in meeting the needs of the modern world.”

Like most liberal Protestants, Mathews had been alarmed by the anti-evolution crusade launched by authoritarian preachers such as Canadian Baptist T.T. Shields of Toronto, Northern Baptist W.B. Riley of Minneapolis and Southern Baptist J. Frank Norris of Fort Worth, Texas.

Mathews preferred the term “modernist” to “liberal” but answered to both. Convinced by the core tenets of evolutionary science and German higher criticism of the Bible, Mathews had undertaken a top-to-bottom re-evaluation of Christian theology.

Drawing on the pragmatic philosophy of John Dewey and William James, Mathews believed the true value of any religion could only be measured by its practical effects. Christianity was “true,” he said, because a belief system grounded in the love of God and neighbor produces positive outcomes.

But this couldn’t happen unless the Christian faith was liberated from a “monarchical” conception of an all-controlling God who sanctified the status quo. It was necessary, therefore, to extend the circle of enlightenment as widely and as rapidly as possible. Under Mathews’ leadership, this was the goal of Chautauqua’s Department of Religion.

During the ‘Trial of the Century’, defense attorney Clarence Darrow points a finger up while arguing for the defense in the center of a crowded courtroom in Chicago, July 1924. The young defendants Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb can be seen seated to Darrow’s right. (Photo by Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection/Chicago History Museum/Getty Images)

The fatalistic skepticism of Clarence Darrow

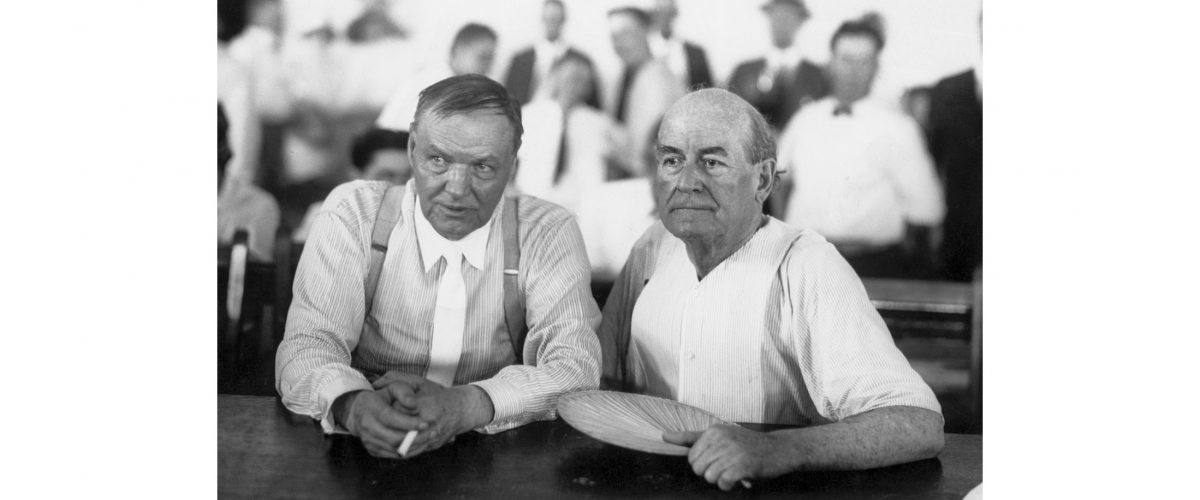

Clarence Darrow’s father was a self-described infidel, and iconoclastic texts and symbols shaped his formative years. A disciple of Friedrich Nitzsche, Darrow embodied the pessimistic outlook of the premillennialists, although for very different reasons. Deeply influenced by Darwin, Herbert Spencer, Marx, Nietzsche and Freud, the controversial Chicago attorney was, in some respects, a true modernist.

Darrow arrived in Dayton fresh from the trial of Leopold and Loeb, two young men who murdered an innocent boy because, after reading Nietzsche, they viewed themselves as supermen who transcended bourgeois standards of right and wrong. Darrow saved his clients from the death penalty by arguing that their parents, their caregivers, their exposure to cheap dime novels, and even the local library (where they encountered dangerous ideas) shared responsibility for their horrible crime.

Defense attorney Clarence Darrow reading his mail during the Scopes trial in 1925. (Photo by George Rinhart/Corbis via Getty Images)

Darrow lived in an unresolved tug-of-war between the power-loving Nietzsche and the pacifism of Leo Tolstoy. By the time Darrow, Bryan and Mathews arrived in Dayton, they all were convinced pacifists. Although they worked from very different premises, they all were dedicated to peace, justice and fairness. None of the three were socialists, in the strict sense, but they all stood in solidarity with the working class.

Darrow was sitting on the stage at the 1896 Democratic Convention in Chicago when Bryan, a relative unknown at the time, strode to the podium. While America could get along just fine without its major cities, Bryan insisted, the nation’s centers of wealth would dry up without the farms and small towns on which they were dependent. So long as America clung to the gold standard, Bryan told the crowd, money would be tight, commodity prices would stay low, and farmers would suffer the consequences. The answer was to expand the money supply by tying the wealth of the nation to both gold and silver.

As a crowd of 25,000 sat in rapt silence, Bryan flung wide his arms and paused for effect. Finally, in a voice dripping with pathos, he delivered what might be the most famous line in the history of American oratory: “You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns; you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold!”

Bryan maintained his cruciform pose for five seconds, then walked off the stage. After two seconds of utter silence, the building shook with an ovation that seemed to go on forever. As marching bands strained to be heard over the din, the Democratic Party embraced its new champion.

William Jennings Bryan speaks at the Sibley Memorial Hospital cornerstone laying in 1913 . (Photo by Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images)

The Social Gospel populism of William Jennings Bryan

Bryan identified with his agrarian fan base at a deep, emotional level. He shared their revivalist piety, their attraction to the Social Gospel, their postmillennial optimism and, tragically, their vicious racism.

Although he served two terms in Congress, made three runs for president as the Democratic nominee (all unsuccessful), and served as Woodrow Wilson’s secretary of state, Bryan was primarily an orator. Although Mathews and Darrow were familiar faces on the Chautauqua circuit, Bryan spent most of his adult life (even when serving as secretary of state) riding the train from one Chautauqua event to the next. The highlight of the most prominent Chautauquas was “Bryan Day.” The man known as “the Great Commoner” is reputed to have spoken more than 3,000 times on the circuit.

Although Bryan was no stranger to the “mother Chautauqua” in Southwestern New York State where Mathews shaped the religious program, most Bryan lectures were delivered to less sophisticated audiences in small Midwestern communities. The men and women who flocked to his lectures lived somewhere between the urban working class and society’s gentile upper crust. Not all were necessarily devout, educated or wealthy, but they aspired to be.

“If he could reinforce a flattering remark with an apt quotation from the Bible, Bryan discovered, the impact more than doubled.”

Early on in his speaking career, Bryan learned the importance of telling his people what they wanted to hear. If he could reinforce a flattering remark with an apt quotation from the Bible, Bryan discovered, the impact more than doubled.

Bryan’s familiarity with Mathews’ reconfigured Christianity was strictly limited, but he knew enough about the new theology to know it wouldn’t fly with his people. Bryan didn’t want Northeastern elites dictating public policy to the men and women he represented. That’s why he agreed to prosecute John Scopes. The citizens of Tennessee, represented by the state legislature, Bryan believed, should be the sole arbiters of what was, and was not, taught in their publicly financed schools.

Harry Emerson Fosdick

A pamphlet war

The fundamentalist-modernist controversy began as a pamphlet war subsidized by wealthy benefactors. The fight began in 1915 with a series of tracts defending orthodox Christianity from its cultured despisers. Funded by oil magnate Lyman Stewart, these modest publications were mailed to virtually every pastor in America.

In 1922, Harry Emerson Fosdick, pastor of First Presbyterian Church in New York City, addressed the escalating controversy with a sermon: “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” A controversy erupted when John D. Rockefeller Jr. disseminated Fosdick’s homily to pastors across the nation. Threatened with a heresy trial, Fosdick was forced to resign.

In response, Mathews and Fosdick edited a series of anti-fundamentalist pamphlets written by leading American pastors, theologians and scientists. Once again, Rockefeller footed the lion’s share of the bill. Since the end of the First World War, Rockefeller had been aggressively pushing “the Interchurch World Movement,” an ecumenical program to coordinate the work of Protestant denominations.

Convinced that Rockefeller was attempting to buy the acquiescence of denominational leaders, fundamentalist leaders were eager to respond. With W.B. Riley leading the charge, conservative pastors, primarily in Southern states, started pushing for legislation outlawing the teaching of evolution in public high schools. When Tennessee passed such a law, the American Civil Liberties Union filed suit on behalf of John Scopes, a high school football coach who had taught a few biology classes as a substitute teacher.

“Most Protestant pastors and denominational leaders wanted no part of the fundamentalist-modernist dustup.”

Most Protestant pastors and denominational leaders wanted no part of the fundamentalist-modernist dustup. Both Bryan and Mathews asked E.Y. Mullins, president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, to throw his considerable reputation behind their side of the fight. Mullins refused. There was nothing to gain, and much to lose, from being associated with either radical theology or anti-science religious reaction.

Battle lines are drawn

Always on the lookout for a media-saturated venue, Clarence Darrow arranged to represent John Scopes before the ACLU could assign legal representation. Concerned that Darrow’s anti-religious reputation might deflect from the First Amendment issues, the ACLU insisted that Darrow solicit expert testimony from church-related scientists and liberal clergymen. Darrow used the pamphlets Mathews and Fosdick had edited to identify appropriate experts.

In the end, Mathews and his modernist associates weren’t allowed to testify before the jury, but their courtroom presence suggested the Scopes trial wasn’t a war between science and religion.

Court scene of Scopes trial, 1925. (AP Photo)

Bryan’s Social Gospel fundamentalism

Bryan entered the anti-evolution fight at the request of Riley. In the early 1920s, Bryan was seen as the face of the fundamentalist movement, but if the Great Commoner had been better acquainted with men like Riley, Norris and Shields, he would have reconsidered.

To his dying breath (which he drew five days after the Scopes trial ended) Bryan was dedicated to a Social Gospel rooted in agrarian politics and an optimistic, postmillennial vision of the future. Unlike Bryan, most fundamentalist leaders had embraced a form of premillennial dispensationalism that viewed the world as a sinking ship. Fundamentalists like J. Gresham Machen and T.T. Shields bucked the premillennial trend, but they were small-government conservatives who had no use for the Social Gospel.

“Even Bryan’s opposition to evolutionary theory was driven by his Social Gospel liberalism.”

Even Bryan’s opposition to evolutionary theory was driven by his Social Gospel liberalism. Since the late 19th century, Herbert Spencer’s phrase, “the survival of the fittest,” had been applied to human society. Advocates of “social Darwinism” argued that the harsh inequities of life are nature’s way of strengthening the human race by culling the herd. Bryan was repelled by this brand of thinking.

Bryan’s anti-evolution crusade was a late development. As late as 1919, he served on the general committee of the Interchurch World Movement. The same year, he called the Federal Council of Churches the “greatest religious organization in our nation.” It was only after 1920 that Bryan started attacking evolution.

After resigning from Woodrow Wilson’s cabinet in 1915, Bryan quickly disappeared from the national stage. He likely saw an assault on Darwinism as the most effective way to recapture the limelight, but his motivation went far beyond personal ambition.

By 1920, Bryan was convinced that “Darwin’s demoralizing guesses” were undermining the only power strong enough to spur genuine reform: the Christian gospel. “By paralyzing the hope for reform,” Bryan asserted, evolutionary modes of thought discouraged “those who labor for the improvement of man’s position.”

The showdown

By moving that the jury should find his client guilty, Darrow eliminated the need for closing arguments. The cagey attorney knew from personal experience how Bryan could capture a room with his oratory and was determined to deprive him of that opportunity. Bryan had labored long over his closing argument and had hoped it would become the crown jewel of his public career.

“The dramatic high point of the Scopes trial came when Bryan unwisely agreed to testify as an expert on the Bible.”

As a consequence, the dramatic high point of the Scopes trial came when Bryan unwisely agreed to testify as an expert on the Bible. The judge allowed Darrow to question Bryan outside the presence of the jury. Since a crowd of 3,000 had gathered to witness the showdown, the inquisition was moved outdoors.

As Bryan fanned himself with a giant palm leaf, Darrow dug deep into his bag of biblical anomalies to befuddle and embarrass Bryan. Darrow’s questions caught Bryan flat-footed and his awkward and testy responses showed little of his famous eloquence. The crowd was solidly behind Bryan, but everyone knew he was out of his depth.

Five years after the Dayton fiasco, Darrow scheduled a science v. religion debate with G.K. Chesterton, a devout Roman Catholic who thoroughly enjoyed a good verbal joust with skeptical friends like Bertrand Russell. When Chesterton freely admitted that the Bible was susceptible to a wide variety of interpretations, Darrow didn’t know how to respond. As Chesterton confided to a friend after the debate, Darrow sounded as if he were “arguing with his fundamentalist aunt.”

Bryan the orator was used to whacking the daylights out of the straw men he invented for the purpose. Confronted with Darrow’s questions, the Great Commoner crumbled.

In the end, the cash value of the Scopes trial was conveyed to the American public through the barbed wit of H.L. Mencken. Friedrich Nietzsche wrote The Antichrist in 1895, but the book was virtually unknown in America until Mencken translated it into English in 1918. Like his German mentor, Mencken despised proponents of Christian altruism almost as much as he loathed the unsophisticated folk who inhabited the farms and small towns of America. Bryan’s close identification with people Mencken regarded as backwoods hicks and religious fanatics made the Commoner the perfect foil for Mencken’s elitist and fervently anti-democratic scorn.

Mercifully, the Commoner never learned how badly his legacy would suffer. “Well, we won our case,” a cheerful Bryan told J. Frank Norris in a letter posted shortly after the trial. “It woke up the community if I can judge from letters and telegrams.”

Three days later, Bryan was dead.

The legacy

A century on, the contours of the Scopes trial are depressingly familiar. If you are like me, the well-worn arguments of religious progressives, skeptics and conservatives are battling in your social media platforms at this very moment.

Qoheleth was right, there is nothing new under the sun. If you think New Atheism is new, you haven’t read Mencken and Darrow. Second verse, same as the first.

The modernism of Shailer Mathews (and the “Chicago School” with which he is commonly associated) were briefly sidelined by the neo-orthodoxy of Karl Barth and the Niebuhr brothers. But Mathews’ conception of an evolving social mind has recently been called a precursor to process thought and linked to a wide array of liberation theologies.

If Bryan had lived as long as Darrow and Mathews, he would have been forced to choose between his Social Gospel populism and continued cooperation with his fundamentalist co-conspirators.

In similar fashion, progressive evangelicals were living in fragile communion with the wider evangelical community until Donald Trump descended from heaven on an elevator of gold. The ever-widening rift between Trump-adjacent and Never-Trump evangelicals mirrors the gulf separating Bryan from the hardcore fundamentalism of his day.

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

In ideological terms, the American religious landscape in 2024 is closer to that of 1924 than it is to 1954. In my next column, I’ll explain what I mean by that.

Alan Bean

Alan Bean serves as executive director of Friends of Justice. He is a member of Broadway Baptist Church in Fort Worth, Texas.

Related articles:

E.Y. Mullins, the piano mouse, the Cowardly Lion, and the monkey trial | Analysis by Brad Bull

The Scopes Trial, then and now | Opinion by Bill Leonard

Tennessee legislators turn back the clock to Jim Crow time | Opinion by Rodney Kennedy