Fifty years later, I wish I could remember 1968.

Fifty years later, I wish I could remember 1968.

The problem is, I was born in December 1961, so for most of 1968 I was 6 years old. Certainly not old enough to comprehend the historic tragedies and victories that unfolded in the year I entered first grade. In fact, the only “news” I remember from that era was getting glimpses of the Vietnam War on our black-and-white TV and going to bed every night praying I would not grow up to be sent to Vietnam.

Everything else I know about the important events of 1968 I learned in college or as an adult. Part of the problem with being born so close to history-making events is that even your high school textbooks can’t catch up in time to cover them. As I recall, my high school American history class barely made it to World War II.

So I asked some friends who are a few years older what they remember of 1968, and the answers were similar to mine: Not much. Even as older elementary students at the time, these friends remained unaffected by the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the assassination of Robert Kennedy, the antiwar protests, passage of the Civil Rights Act, the Poor People’s Campaign, civil unrest in Chicago.

Besides American astronauts being launched into orbit around the moon, the main thing all of us remember is the war. And the casualties of war.

One friend, who was 10 years old in 1968, remembers a 19-year-old from his small town being killed in Vietnam. “He was a local boy, and his family lived in a fine brick home just north of town. I can remember the almost claustrophobic feeling of the crowd of people inside the funeral home. Vietnam was not an abstract thing to me. I did not have a clear sense of any moral obligation to stop communism, but I felt that war was a terrible thing that had snuffed out the life of a 19-year-old.”

“Will today’s children raised in ‘good Christian homes’ know anything of social activism, of Christian advocacy?”

Another friend, who turned 12 in 1968, recalled the only thing to puncture the conservative evangelical bubble in which his Baptist family lived was the nightly commentary of TV news anchors Chet Huntley and David Brinkley. “A constant memory of that era was the nightly body count – how many young men died that day in Vietnam. Collectively, those reports comprise one of the strongest memories of my childhood.”

Yet another friend, who also turned 12 in 1968, explained: “My parents weren’t very keen on the changes in society or very news savvy either. I think they mostly bought the propaganda about King being a Communist and focused on his marital infidelity. Robert Kennedy was a blue blood and a Democrat. The Vietnam War wasn’t a big topic in my house. About the most I can remember was talk of all the soldiers who got hooked on drugs over there. It feels like we were in a coma.”

Then this friend summarized his adult view looking back at his parents 50 years ago: “For both of them, there was no clear sense of what was at stake in our country. They were selective in what they heard and how they viewed things, and generally I think they were somewhat afraid that all the protests would be destabilizing to the world they knew. Just nothing at all about social justice.”

All the 50th anniversary talk of 1968 this year has made me wonder what today’s children will remember of the tumultuous events of 2018. How has the expansion of TV news coverage, the birth of the Internet and the presence of social media changed how much children know and how much their families talk about current events?

“One of the greatest blind spots of white privilege is the ability not to talk with your children about critical issues of the day, to ‘protect’ them from reality.”

It feels like today’s parents may be even more protective of their children than our parents were 50 years ago. It also feels like those attempts may be more futile than ever before. And what is the role of the church in all this? How much should children’s Sunday school teach the subversive nature of what it means to follow Jesus?

Will today’s children raised in “good Christian homes” know anything of social activism, of Christian advocacy?

All this reminiscing brought me back to a song written in 1968 but which I would only learn much later: “Teach Your Children Well,” by Graham Nash. You likely know the song from its 1970 recording by Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. The second verse says: “And you, of tender years, can’t know the fears that your elders grew by. And so, please help them with your youth; they seek the truth before they can die.”

One of the greatest blind spots of white privilege is the ability not to talk with your children about critical issues of the day, to “protect” them from reality. Black parents don’t have this privilege. Hispanic parents don’t have this privilege. Poor parents don’t have this privilege. Immigrant parents don’t have this privilege. My parents had this privilege, even though they would have been sympathetic to integration. The point is, they didn’t have to talk about, though.

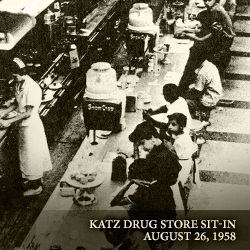

Which is why I was shocked a few months ago to read about the 60th anniversary of a pivotal event in black history in Oklahoma City, where I grew up. Except that I grew up in an all-white suburb where I knew no black people, no Jews and one Catholic. Why would I have known about the 1958 Katz Drug Store sit-in? But on the other hand, how could I have gone all these years without ever hearing about it? Shouldn’t this have been an important part of local history?

Which is why I was shocked a few months ago to read about the 60th anniversary of a pivotal event in black history in Oklahoma City, where I grew up. Except that I grew up in an all-white suburb where I knew no black people, no Jews and one Catholic. Why would I have known about the 1958 Katz Drug Store sit-in? But on the other hand, how could I have gone all these years without ever hearing about it? Shouldn’t this have been an important part of local history?

I’m not a child psychologist, so I can’t tell you exactly what’s appropriate for children to know at what age. But I am a parent who has raised two kids and a pastor who interacts with children and youth and families every week. We know that racist parents have no reservations about teaching their children their narrow views from an early age; they model bigotry proudly, and children easily imitate it.

The challenge for the rest of us in 2018 is to be thoughtful about what we model, what we say, what we teach. It would be a tragedy if the children of today get to 2068 and are able to say, “I never knew that happened in 2018.” We’ve got to teach our children well.