Gandhi helped free me from prison.

Now there’s some fun with syntax and the ambiguity of a preposition. That sentence has two potential meanings: Either Gandhi helped me get out of prison, or, while he was in prison, Gandhi helped me gain freedom.

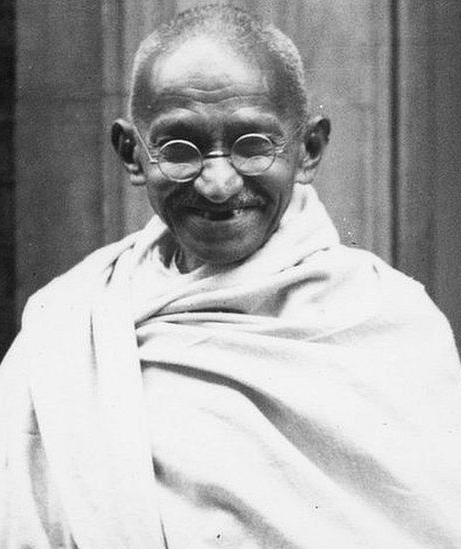

Since he had been dead a few decades before I was born, he did not help me get out of prison. Rather, Gandhi’s imprisonment helped me in the journey to apply the soul-saving message of another person who did hard time. The Apostle Paul said to “be transformed by the renewing of your mind” (Romans 12:12), and part of Gandhi’s story continues to help me do that.

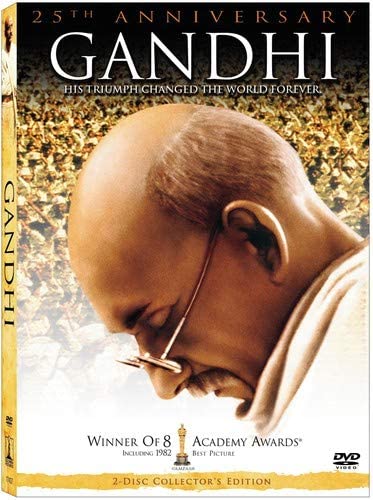

In the summer of 1983, Gandhi had been dead 45 years. Yet his story rocked my world. That summer, between my junior and senior years in high school, I was an exchange student to France, living with a dear family a few hours southwest of Paris. The father, teen son and I went to Paris for three days. On the second day, we were sitting at a stop light, and I was staring at a theater marquee that said, “Gandhi.” The son said, “Do you want to see that movie?” I said yes just as the light turned green, and the father told us to quickly jump out of the car.

In the summer of 1983, Gandhi had been dead 45 years. Yet his story rocked my world. That summer, between my junior and senior years in high school, I was an exchange student to France, living with a dear family a few hours southwest of Paris. The father, teen son and I went to Paris for three days. On the second day, we were sitting at a stop light, and I was staring at a theater marquee that said, “Gandhi.” The son said, “Do you want to see that movie?” I said yes just as the light turned green, and the father told us to quickly jump out of the car.

I walked into that theater as a narrow-minded kid from rural East Tennessee. I walked out with a much broader worldview — theologically, socially, and intrapersonally.

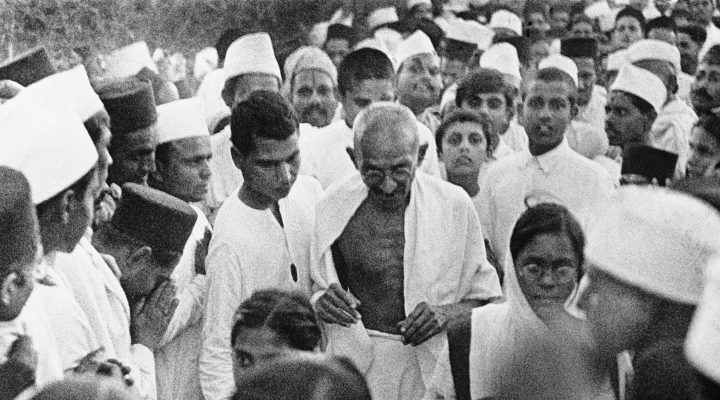

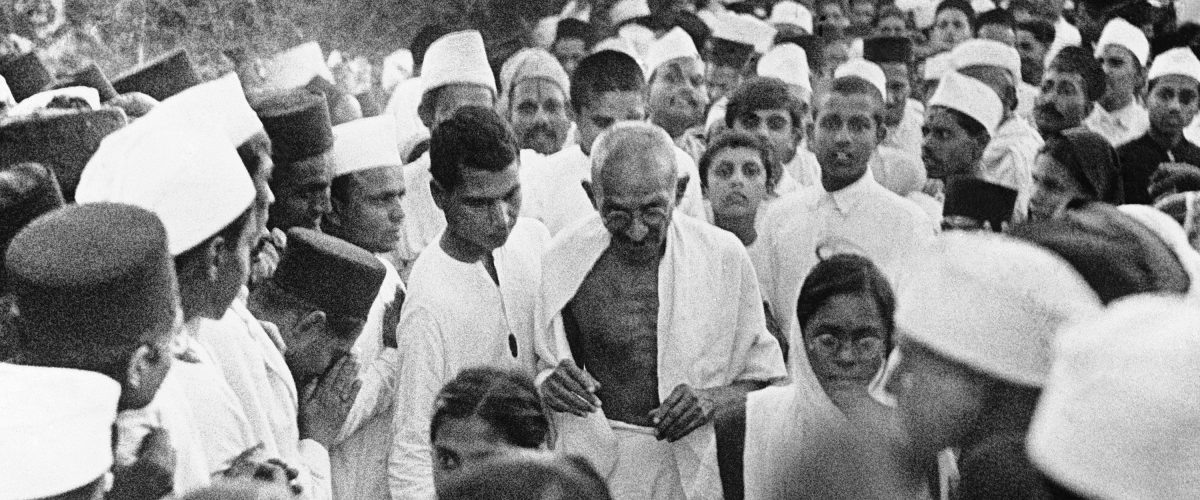

Yes, I was in awe of Gandhi’s courage to endure beatings. Yes, I was awakened to the possibility of inclusiveness in God’s family. Yes, I was inspired by passionate nonviolent means of speaking truth to power. Yet, something else has over and over again carried me through life’s basic and most devastating hardships.

In one scene in the movie, Gandhi pleads guilty to trying to undermine colonial British rule — the same charge leveled against American patriots like John Adams and Nathan Hale. A British judge who admires Gandhi reluctantly and remorsefully imposes a mandatory six-year prison sentence. While the movie runs more than three hours, 191 minutes cannot possibly capture all of Gandhi’s history-making life. When the judge imposes the sentence of six years, the camera shows Gandhi’s face filled with pained resolve. Then the film fades to black. After a few seconds, it fades back in to a scene of desolate countryside.

A subtitle appears: “Some years later.”

Wait! What? We just skipped how long? What happened? (I just sighed out loud all these years later.)

Did he have to serve the whole six-year sentence? What happened in those six years? If he served all six years, how many years is this scene after those years? And what happened during his sentence? Was he assaulted? Did he languish? Did he write?

“Some years later” is so ambiguous.

During the year after seeing that movie, I fell in love. Eventually, my girlfriend left to go out of state to college. We had decided to see other people, but my heart wasn’t in it. I missed her desperately. I couldn’t concentrate on my homework. I wrote her letters and floundered in a barrage of Cs that wrecked my college GPA.

“In the movie of your life, these weeks will be reduced to a caption.”

Early on, I was sitting in my dormitory lobby trying to study on a gloomy, rainy day. I counted the weeks before I would see her again. It seemed like it would be forever. Then, I remembered the phrase, “Some years later.” I thought, “Dude, Gandhi was in prison longer than you will be in college. In the movie of your life, these weeks will be reduced to a caption.”

Ha! Nineteen-year-old me literally thought those weeks of pining would be worthy of at least a caption. Now, in my late 50s, I am a wounded veteran of far worse of life’s battles. Even though I have handled some of those battles very poorly, one thing that helped me through them was imagining a movie screen where that part of my life was a fade to black followed by a fade in with the words “Some years later.”

Some clients with whom I have shared that story have even made it a mantra. One said: “I told that story to my family. Now when we talk about what we are going through, we look at each other and say, ‘Some years later.’”

It’s not an avoidance of the problem. It’s a statement of hope that the problem will be addressed, endured and redeemed.

When my daughter was in third grade, she started facing mean-girl politics for the first time. Some girls wanted to start an exclusive playground club. She didn’t want to exclude anyone, refused to join the club and went to play with the outcasts. The queen-bee girls started tormenting her. One day she so dreaded their bullying, she didn’t want to go to school.

I said: “You know what? I don’t have to be anywhere this morning. So, I’ll give you a choice. You can go to school, or you can do Daddy School this morning, and go to school about lunchtime.”

She looked wary. “What’s Daddy School?” I shrugged, “You won’t know until you try it.” She opted for Daddy School.

We watched the first half of Gandhi. If you’ve seen the movie, you know the first half ends with the horrific depiction of the massacre of Amritsar, followed by Gandhi looking over the blood-stained aftermath. When the word “Intermission” came onto the screen, I hit pause, and we sat in silence for a few moments.

Then, I said, “Hon. If Gandhi and his followers could endure beatings, imprisonment, humiliation and death, can you deal with these girls on the playground?”

She somberly nodded. Then we drove to school. Later that day, she got off the bus smiling her usual bright smile. Were the problems solved? No. But she had hope that she could deal with them. Then later she followed protocol, met with the principal, and that did solve the problem.

Remember my ambiguous opening sentence? “Gandhi helped free me from prison.” Something ambiguous is wandering in meaning, unclear, vague.

Sentences can be ambiguous. In that sentence, do I mean written sentences or prison sentences of indefinite length?

Yes. I mean both of those.

There are many things in life that are ambiguous. Three of the biggest of life’s ambiguities are the past, the present and the future. Each has the meaning we give them.

Some would say the past is clear because we know what happened. First, we often don’t know exactly what happened. Second, when we do know what happened, we often don’t know why it happened, leaving the interpretation very difficult. This is why historians debate.

“If our lives are boiled down to a movie, how much of them will be reduced to a subtitle?”

At the end of each year, we often engage in reflection on the years gone by, the present and the implication for our movement into the new year. There is much ambiguity. Our trials can feel like a prison sentence. If our lives are boiled down to a movie, how much of them will be reduced to a subtitle?

Ghandi

Thank you, Paul. Thank you, Gandhi. Thank you, movie makers. You have inspired me to transform my life by renewing my mind with the hope of turning pain into a subtitle.

But to you, injustice; be warned. Good must logically prevail. This is because for evil to have its temporary successes, it requires goodness. For an evil plot to succeed, it requires the plotter to have intelligence, memory and creativity. All these things are eternally good. (Thank you, Plato.) Thus, since evil cannot exist without goodness, there always will be a flickering spark of goodness that will eventually ignite a renaissance of goodness. Thus, goodness must, in the long run, prevail.

Of course, the fact that goodness must prevail in the ontological sense has little practical benefit to those who are facing death or to a society that could destroy itself with nuclear weapons. While the pain of Gandhi’s imprisonment was omitted from the movie, other horrors, including his assassination, were not.

We must not use the hope of eternal goodness to cause us to betray those who are suffering. We should not blithely say, “God is in control” in response to threats to the world in which we are stewards. If we add $5 to our optimism, we can buy a homeless person a cup of coffee at Starbucks. Without that $5, we have no practical impact.

Yes, evil is temporary while goodness is eternal. However, rather than see that as an excuse for passivity, we must consciously choose to use hope as comfort in the midst of taking action.

As Gandhi said: “When I despair, I remember that all through history the way of truth and love have always won. There have been tyrants and murderers, and for a time, they can seem invincible, but in the end, they always fall. Think of it — always.”

In the midst of that comforting thought, he took action.

So, to you, Injustice; to you, Vocational Distress; to you, Broken Relationships; to you, Bullies: realize your destiny is the fade-to-black-abyss of “Some years later.” The past and future may be mysterious, but through the relativity of time and the logic of causality, hope is clear: In the movie theater of life, the light of goodness continues to beam from eternity to here and from here to eternity.

Brad Bull

Brad Bull is a movie fanatic who had a set of peak spiritual experiences while watching Gandhi then later during Alien 3. He has served as a hospital chaplain, associate pastor, substitute teacher and university professor. He currently is a writer, speaker and marriage and family therapist in private practice. His counseling and retreat services operate from DrBradBull.com.