Architect and art historian Hadley Arnold knew she was in for some surprises when she began transforming an 1830 Rhode Island church into a second home; but she certainly didn’t expect to discover one of America’s most significant works of religious art.

There, above the abandoned pews, in illuminated stained glass, hung one of the earliest known depictions of a Black Jesus in a public space.

St. Mark’s Church in Warren, R.I., which closed in 2010, had been slated for demolition when Hadley and Peter Arnold bought it. Because of the dense pebbled glass storm windows protecting them, Arnold hadn’t been able to examine the images of Christ up close, but she had a hunch there was something special about them. When the storm windows were removed last summer as part of the renovation process to exchange the stained glass for clear, she finally got that closer look.

Black and brown characters

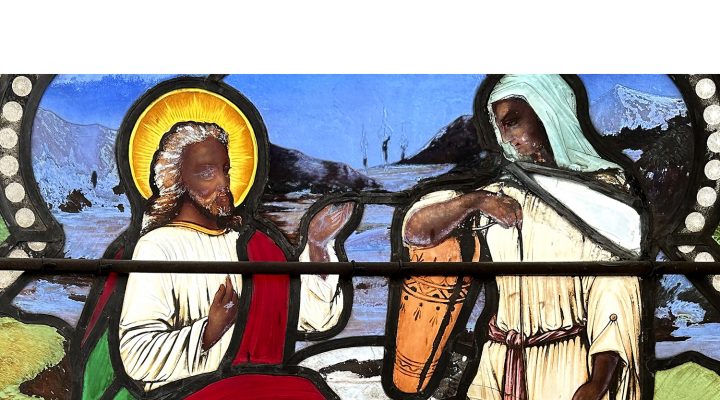

A nearly 150-year-old stained-glass window is displayed Monday, May 1, 2023, inside the now-closed St. Mark’s Episcopal church, in Warren, R.I. (AP Photo/Mark Pratt)

The 12-foot tall, 5-foot wide window, which was installed in 1878 and designed by Henry Sharp studios in New York, features a top panel depicting Jesus at the home of Mary and Martha (Luke 10: 38-42) and a bottom panel of Jesus with the Samaritan woman (John 4:7-30). But what Arnold needed to confirm was the coloring in the glass itself. The figures of Jesus and the women all appeared to have brown skin. But was this on purpose or the result of changes that occurred in the stained glass pigment over time?

Arnold contacted a local museum, which put her in touch with Virginia Raquin, an expert on American stained glass and a professor at Holy Cross.

“She climbed right up on that scaffolding, and she literally spun around and said, ‘This is original and intentional,’” Arnold recalled. Some of the black paint in the figures’ hair has flaked off; but the brown coloring used to create the skin tone is the original and has remained intact.

“Colors in glass can flake off, but they don’t change like oil paint, because they are fired into the glass,” Raquin said. Sharp made three other windows for St. Mark’s dating from 1868 to 1880, but in those other windows Jesus has decidedly milky white skin.

“This is not a discoloration;, this was a deep intention.”

“For me looking at this, it’s liberating! It’s so very liberating and empowering for me being able to see this, and having some of that historical narrative to say, this is not a discoloration; this was a deep intention,” said J. Lee Hill Jr., canon for racial justice and healing at the Episcopal Diocese of Virginia. “This is the Black Christ, and it’s deeply impactful, particularly as a person who 99% of the time is walking into historic churches and gazing at windows and seeing nothing that looks like me, certainly not Christ.”

What the glass portrays

The window is comprised of two colorful panels of stained glass. In the upper panel, Martha stands holding an amphora and bread, and Mary sits in front of her at Christ’s feet, her hands folded in her lap. In the bottom panel, the Samaritan woman leans on her water jar while listening to Jesus seated beside the well.

“It’s incredibly beautiful. The colors are really fantastic,” said an African American artist and fellow at the Virginia Museum of Fine Art who wished to remain anonymous, “You have Jesus with his hand open and his finger raised, and an open hand is like a kind gesture. In stained glass of a religious nature, generally Jesus is somehow exalted, and looking at this, with the Samaritan woman, he’s not. So that is interesting.”

Although the scenes are based on 19th century Bible illustrations, they’ve been altered in significant ways to bring the figures closer together.

“This is a radical statement about fundamental equality of persons.”

“Women and people of color are shown as equals. No one is triumphant or commanding. This is a radical statement about fundamental equality of persons,” Raquin said. According to Hill, the portrayal also is significant from a spiritual perspective because it’s women “who carry the day for the religious life of the Black community.”

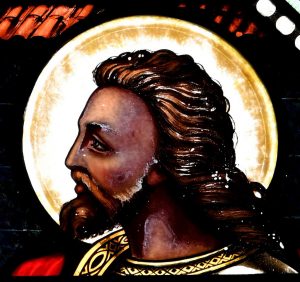

Jesus with dark skin in a window for St. Mark’s Church in Warren, R.I., 1877. (Photo by Michel Raguin)

The window featuring Christ and the women is a departure for the Sharp company, which primarily created stained glass windows depicting solitary figures suspended in space. The finely painted landscapes of contemporary Jerusalem in the background of the St. Mark’s window predate by 20 years similar innovations by Louis Comfort Tiffany. During the 1800s, landscapes in oil paints or watercolors often were the purview of female artists, and Raquin believes it’s likely Sharp hired women to create the backgrounds for this special window.

The window’s commission

The window was commissioned in 1877 by Mary P. Carr in honor of her two aunts, sisters Ruth Bourne DeWolf and Hannah Bourne Gibbs. Carr herself had lost all her other family members by the time she was 35, and it could be the sisters occupied a special place in her life as a result. The exact reason behind her choice to memorialize them with a window depicting Jesus, Mary, Martha and the Samaritan woman as persons of color is a little more complicated.

Both women were donors to the American Colonization Society, an organization dedicated to transporting formerly enslaved Americans to a colony in a part of Africa, now Liberia, to live “free and Christianized lives.” This movement was popular in churches and with some politicians, including Abraham Lincoln. However, Frederick Douglass criticized this scheme, saying it was “mean and impudent in the extreme, for one class of Americans to ask for the removal of another class.” White supremacy cloaked in moralism is still white supremacy.

James DeWolf

What makes the sisters’ involvement in the ACS noteworthy is that when Ruth wed John DeWolf, she married into the largest slave-trading family in U.S. history. Three generations of DeWolfs were responsible for transporting 11,000 enslaved Africans across the Middle Passage. John handled the business correspondence and presided over the Bank of Bristol, which the family founded to manage all the money they made from the slave trade. His brother, James, was charged with murder on the high seas when he tied an enslaved woman with smallpox to a chair, blindfolded her, gagged her and lowered her overboard to her death.

Hannah Bourne married a ship captain, Jabez Gibbs, who worked for the DeWolf family transporting enslaved Africans to southern ports like Savannah, Ga. Both couples married late in life, the men having already made their fortunes in the slave trade.

Retracing the route

DeWolf descendant Katrina Browne was in seminary when she received a booklet written by her grandmother about the family’s history. “I decided to retrace the slave trade route of my ancestors. From Rhode Island to Ghana to Cuba and back,” Browne says in a documentary about her trip.

Rhode Island was one stop on what was known as the Triangle Trade. There, sugar from the Caribbean was made into rum, which was then exported to West Africa in exchange for captives to work as slave labor on the sugar plantations. The DeWolfs owned several plantations in Cuba. “These plantations supplied sugar and molasses needed to make the rum back in Bristol,” Browne explains. “They also served as holding places for the Africans while the DeWolfs waited for slave prices to go up.”

“The economy of Rhode Island was steeped in the slave trade.”

Although Rhode Island abolished the slave trade in 1652, the ban never was enforced. Between 1709 and 1807, the colony transported 106,544 enslaved Africans to the Colonial United States. “The economy of Rhode Island was steeped in the slave trade. It was the leading slave trading state in the country,” Browne notes. Even after the Revolutionary War, the state remained the epicenter of the North American slave trade, controlling between 60% and 90% of the business.

Holy Cross professor and stained-glass expert Virginia Raguin speaks to a group of middle school students, Monday, May 1, 2023, while standing near a nearly 150-year-old stained-glass window that depicts Christ speaking to a Samaritan woman, in the now-closed St. Mark’s Episcopal church, in Warren, R.I. (AP Photo/Mark Pratt)

Were the sisters attempting to atone for their ill-gotten wealth by donating it to the ACS?

“If their husbands are making money off the slave trade, they don’t really have a choice. What are they going to do?” said the artist from the VMFA. “If they don’t agree with slavery, maybe it is an act of rebellion. Ruth Bourne DeWolf left a substantial portion of her estate to the Episcopal diocese, and, according to Browne, the DeWolf family financed several windows in St. Michael’s Episcopal Church in Bristol, R.I., where she and her husband were members. There can be little doubt that if Mary Carr’s childless aunt left her an inheritance, it was money made off the trafficking and sale of human beings.

It’s possible Mary Carr didn’t need her aunt’s money to pay for the window in St. Mark’s. A potential relative named Caleb Carr in Warren, R.I., built a 300-ton brig for James DeWolf in 1812. Warren began trading slaves illegally in 1789, launching the first of 30 voyages to Africa. Five hundred captured Africans would die en route, while 2,400 were enslaved upon arrival in the Americas. Many of the town’s early politicians, benefactors and judges grew wealthy off the slave trade. Streets were named in their honor, and their grand historic homes are still standing in Warren today.

“Her Black life did not matter except for the 50 pounds she was worth.”

Pat Mues, founder and co-chair of the Warren Middle Passage Project, brought this to the attention of the local community in a letter to the editor: “The slave trade and enslavement in Warren were an integral part of the town’s commerce and life from its founding until the last enslaved person was freed early in the 19th century. The first local record of enslavement is in the minutes of the third town meeting in 1747 in which the inventory of an estate lists ‘One Negro woman.’ No name, no further description, no explanation of her fate. Her Black life did not matter except for the 50 pounds she was worth.”

Attempt to atone?

Was Mary Carr also trying to make amends as the beneficiary of slave trade money by donating the window in her aunts’ memories? The political landscape at the time of the window’s commissioning suggests one possible motivation. In 1876, the nation was still very much divided after the Civil War. During that year’s presidential election, neither party’s candidate received enough Electoral College votes to win outright. Several Southern states returned disputed slates of electors, leaving 20 votes up for grabs.

The now-closed St. Mark’s Episcopal church in Warren, R.I. (AP Photo/Mark Pratt)

To swing disputed votes his way, the Republican candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes, agreed to remove federal troops from the formerly Confederate states and end Reconstruction. This left newly freed African Americans vulnerable to white state and local governments and ushered in the era of Jim Crow.

“In the middle of Reconstruction, Black folks were finally being viewed as American citizens of this country. There was this ability for Black folks to grab as much power as possible, until it became problematic,” Hill said.

Perhaps Mary Carr commissioned the window honoring her aunts as a reminder to the members of St. Mark’s to continue to care for those who would be left disenfranchised and subject to segregation in the south. Or maybe she was inspired by the progress African Americans had made during Reconstruction.

“It offers another glimmer of hope,” continued Hill. “While there was still racism, there was this kind of balancing during this time (of Reconstruction). So that makes this an even more powerful witness, realizing what was happening.”

While the American Colonization Society had been declining in the decades following the Civil War, there was an upswing in interest even among African Americans in the 1870s after the failure of Reconstruction. The stated purpose of the ACS was “to see Christ in Africa and Africa in Christ.”

“It would appear she is honoring people of conscience, however imperfect their actions or their effectiveness may have been.”

Was the window an attempt to visually represent “Africa in Christ” by portraying Jesus and these biblical figures as African? It’s a tenuous connection, although not entirely without merit. “It would appear she is honoring people of conscience, however imperfect their actions or their effectiveness may have been,” Arnold said. “I don’t think it would be there otherwise.”

What’s the message?

Although the window’s ties to the slave trade and the ACS remain problematic, there are other challenges to consider when evaluating its impact and importance. How does the stained-glass window’s provenance affect its message? This is a window commissioned by a white woman, honoring white women, created by a white company and displayed in the church of a white congregation.

J. Lee Hill Jr.

Therefore, whatever the window is trying to say about Black people, it is not necessarily what they might say about themselves in the 19th century — or about Jesus, Mary, Martha and the Samaritan woman. The religious paintings of Henry Ossawa Tanner or the art of Edwin Mitchell Bannister, who spent much of his time in Rhode Island, might provide some clues to what a Black interpretation might look like; but their works also conform to the prevailing tastes and techniques of the time, which were heavily influenced by the work of white artists. When asked if the artwork were done today, what might be different, the African American artist laughed and said, “I think Jesus would have an afro for starters, not this billowing hair.”

The fact that the window raises so many questions and is so thought-provoking may work to the good as Arnold and Raquin, along with other historians and museum experts, determine its future. Their hope is to find a permanent home for the window, one where it can continue to be a source of discussion and debate, such as a museum or university.

“The whole premise behind art is to get people to think,” said the African American artist. “I think it would be lovely for that widow to be respected as a piece of amazing art, because it is, and I think it would be nice for it to be somewhere public where it could be seen and cared for.”

“Stained glass windows like these invite more stories from individuals who have been marginalized and oppressed.”

“Stained glass windows like these invite more stories from individuals who have been marginalized and oppressed,” Hill added. “Being able to see that and to employ it as a tool to engage becomes a powerful historical witness.”

The window itself is too fragile to tour, but there is talk of creating a digital version along with curriculum for school children. A diverse group of eighth graders from a Jesuit boys’ school already has taken a field trip to see the window, as have several college classes and a group of Ph.D. students from Brown University who afterward hosted a roundtable discussion about the window.

What has not yet been considered is how churches can and should engage what is, at its core, a religious work of art. The stained glass window originally was installed in St. Mark’s as a conduit for religious devotion.

After completing her exploration into her family’s past, Katrina Browne worked with the Episcopal church to create Sacred Ground, a dialogue series on race and faith as part of their Becoming Beloved Community initiative. “The 10-part series is built around an online curriculum that focuses on indigenous, Black, Latino, and Asian/Pacific American histories as they intersect with European American histories,” Browne explained. “Participants are invited to peel away the layers that have contributed to the inequities of the present day — all while grounded in our call to faith, hope and love.”

“We have to tell the truth about those stories and those narratives, because it is only by speaking the truth that we are able to find a pathway to freedom and liberation,” Hill said. “And that means we have to hear stories and narratives that have been pushed aside and marginalized and we have to bring those stories to the center.”

The work of racial justice is complicated, and full of the efforts of well-meaning white people like Ruth Bourne DeWolf, Hannah Gibbs and Mary Carr. Thankfully there has been grace from the African American community for such efforts, even when they prove misguided.

Churches must atone for their own complicity and the many ways they have benefitted from systemic racism. How many windows, roofs, steeples and pews in American churches were financed with money from the sale and labor of those enslaved? How many churches were built from bricks made by convict labor during the era of Jim Crow? How many members tithed on the prosperity denied to their African American neighbors because of the discriminatory practice of redlining?

The window from St. Mark’s provides a great starting point for congregations who want to undertake these complex and uncomfortable conversations. Hill says the depiction of a Black Jesus in stained glass gives him hope. “It gives me a hope of what can be, because of what has already been. My job is to walk with clergy and congregations and institutions and individuals in this work. Among those that are willing to hear and willing to see, and that are willing to think out loud about race, there is tremendous growth that is happening in their orientation to the world. And that, for me, gives me great hope.”