In the past few weeks, I traveled to New York City and Washington, D.C., in support of research, collaboration and programming supported by Baylor University and the Baugh Foundation. I met with a number of principals at Washington National Cathedral to talk about the Cathedral’s continuing commitment to racial justice, our partnership on that work, and about the Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson stained glass windows the Cathedral removed from the nave early on in the process of reckoning with Confederate monuments. I met with folks at Trinity Church Wall Street in Lower Manhattan to talk about how my deep dive into racist myths might fit into their coming plans on racial reconciliation. With my friend Kelly Brown Douglas, one of America’s most important Black theologians, I participated in the first programming growing out of my grant — a race, film and reconciliation program in Brooklyn mere blocks from where Spike Lee filmed Do the Right Thing.

Greg Garrett

But what is sticking with me from this trip besides the joy of actual human contact — like many of us, I have had far too little of that over the last 18 months — are the two visits I made to national monuments, monuments that tell stories that fly under the mainstream radar on race. These two tales from great cities could help us confront and repair our understandings of how America was built on the backs of enslaved people and help us see how those people proved their humanity time and time again in the face of hatred, ignorance and fear.

Manhattan burial grounds

The African Burial Ground National Monument is a patch of green and granite surrounded by towering buildings in downtown Manhattan, mere blocks from New York’s City Hall and from Wall Street. Although I have been coming to Manhattan for more than 30 years, I knew nothing about the burial ground until I read about it in Clint Smith’s essential new book How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery across America.

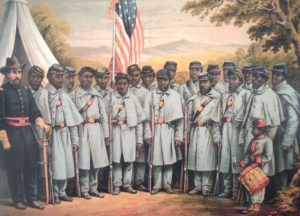

Engraving showing enslaved Africans involved in building New Amsterdam, which is modern New York City.

Smith reports that enslaved people were brought to New Amsterdam in 1626. They chopped down trees, built homes and roads, and helped create the lasting framework for the city that never sleeps. “It’s likely,” he writes, “that some of the wood they cut from trees in lower Manhattan was used to build ships that eventually carried captured Africans” back to the colonies.

When we think about race and slavery, he suggests, Americans have a tendency to relegate slavery solely to the South, when the truth is that enslaved people helped build Manhattan. The monument — which grew out of the accidental discovery of more than 15,000 graves of free and enslaved Africans during excavation for a federal office tower — reminds us that slavery was a reality throughout the colonies, and as my own research and reading suggests, the backbone to American prosperity both North and South.

Door of No Return

The monument is powerfully affecting. To enter it, you step through a tiny entrance reminiscent of the Door of No Return in Senegal that an untold number of slaves may have passed through on their way to a brutal new existence in America — if they survived the passage across the Atlantic. Once through the entry, you stand on a depiction of the world with Africa at its center, representative of the African diaspora, of the enslaved people sent to the New World who helped to build the American culture we now cherish.

I wrestle often with shame in this study of racism and repair that has claimed me over the past five years, but I must say that this monument not only informed me, but it also centered me. In 1993, the remains that had been excavated — nearly half of them children — were reinterred with all honors, ceremonies and libations under seven re-burial mounds. The land where the monument stands, a tiny island of green amidst those American towers, remains as a memorial to those who built New Amsterdam and Manhattan and a reminder to all of us of the pervasive presence of slavery.

Looking at the burial mounds, Clint Smith remembers that “I thought of all that lay beneath the layers of grass and soil and stone — the history, the stories.” Smith’s book captures our national sin, but the strength and courage of his African American ancestors also constantly emerges. The formal and informal rebellions, the acts of self-determination where an enslaved person chose death or escape to a life of servitude, and of course the example of all those Black soldiers who fought for the Union in the Civil War are constant rejoinders to the myths of cowardice and incompetence attached to African Americans.

African American Civil War Memorial

African American Civil War Memorial

Just off U Street in a historically Black section of D.C. near Howard University, you can find the African American Civil War Memorial, a statue commemorating the more than 200,000 troops who fought for freedom and equal rights. In his 1863 article “Why Should a Colored Man Enlist?” Frederick Douglass set down a number of compelling reasons, not least that it stood in opposition to every racist myth about African Americans:

You are a member of a long enslaved and despised race. Men have set down your submission to Slavery and insult to a lack of manly courage. They point to this fact as demonstrating your fitness only to be a servile class. You should enlist and disprove the slander, and wipe out the reproach. When you shall be seen nobly defending the liberties of your own country against rebels and traitors — brass itself will blush to use such arguments imputing cowardice against you.

Confederate Gen. Howell Cobb once told the Confederate Secretary of War James A. Seddon that if slaves could successfully become soldiers “our whole theory of slavery is wrong.”

They could, and they did. They fought bravely, with discipline, with intelligence and initiative, proving Cobb’s point, and completely refuting the racial mythologies that said Africans were fit only to be in servitude. The nearby African American Civil War Museum off U Street is a small gem, documenting thoughtfully and thoroughly the many ways that Black soldiers helped their Southern sisters and brothers gain freedom.

Clint Smith is absolutely correct — the history, the stories about race, matter more than we can know. For 400 years, white American writers, thinkers, legislators and theologians told false stories about who Africans were and what they could do. They minimized and continue to minimize the extent to which slavery shaped and built America. But if we listen, if we pay attention, if we open our eyes, we will see the truth.

Clint Smith is absolutely correct — the history, the stories about race, matter more than we can know. For 400 years, white American writers, thinkers, legislators and theologians told false stories about who Africans were and what they could do. They minimized and continue to minimize the extent to which slavery shaped and built America. But if we listen, if we pay attention, if we open our eyes, we will see the truth.

Our 400-year history of racism is shameful. But the opposing stories are powerful, compelling, and completely expected: People of color were and are completely human, their lives demonstrated and demonstrate courage, creativity and tenacity, and any attempt to suggest otherwise is as doomed as those Lee and Jackson windows in Washington National Cathedral.

History is on the march, and truth is in the vanguard, thanks be to God.

Greg Garrett is an award-winning professor at Baylor University. One of America’s leading voices on religion and culture, he is the author of more than two dozen books, most recently In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett and A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. He is currently administering a research grant on racism from the Eula Mae and John Baugh Foundation and writing a book on racial mythologies for Oxford University Press. Greg is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church and Theologian in Residence at the American Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Paris. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

Related articles:

Greg Garrett, Baylor prof and BNG columnist, awarded Baugh grant for research on race and media

‘They’re like children’: Confronting the myth of white paternal control | Opinion by Greg Garrett

Films on race can help us have hard conversations | Opinion by Greg Garrett