By Jeff Brumley

The term “Baptist peacemaking” conjures up images of President Jimmy Carter observing elections on troubled continents. For others it means human rights activists brokering peace deals between warring factions in Africa or the Middle East.

But it doesn’t mean only that, says LeDayne McLeese Polaski, the program coordinator for the Baptist Peace Fellowship of North America.

Peacemaking can also include actions like mentoring inner-city children and writing members of Congress about public policy issues trying to understand why a local school is under-resourced, Polaski said.

Basically, any action that promotes justice leads to peace, and that means a lot of Baptists and other Christians are peacemakers without even knowing it.

“Part of our job is to help others see what they are already doing and name it as peacemaking,” Polaski said. “A lot of churches are already doing something.”

Creating new traditions

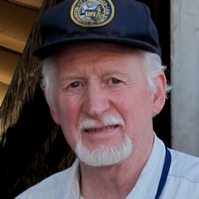

The nature and state of Baptist peacemaking has entered the spotlight with the April 26 death of Baptist theologian Glen Stassen, known for his writings and teachings on the ethics of war and peace.

Stassen, who was 78 when he died in California, taught at Southern Baptist Theological and Fuller Theological seminaries, among other colleges and universities. He was for 30 years a leading voice for peace and his groundbreaking book, Just Peacemaking, promoted positive and practical steps to end war.

Stassen propelled Baptists into a Christian context where the active peace movement was led by Mennonites, Quakers and others.

“Glen Stassen created a new tradition for peacemaking among Baptists,” said Robert Parham, the founder and executive director of the Baptist Center for Ethics and a former student of Stassen’s at Southern.

Parham and other members of an ethics course taught by Stassen drafted a resolution in support of nuclear arms control. The resolution was adopted by the Southern Baptist Convention in 1978.

‘On the outer circle’

The core of Stassen’s theology on peacemaking was that the Sermon on the Mount was a commandment his followers were to take seriously, Parham said.

“He challenged the common reading in many churches that [the sermon] was an idealistic statement,” he said. “Glen believed it was a realistic statement.”

He also lived out his theology, still traveling the world as an advocate and activist for peace.

He also lived out his theology, still traveling the world as an advocate and activist for peace.

But Stassen’s single-minded focus on peacemaking didn’t make huge inroads in Baptist life, Parham said.

While working to educate and motivate Baptists to take a practical view of the Sermon on the Mount as the basis for peacemaking and human rights, he was limited by a denominational context “where Southern Baptist fundamentalists were more committed to Leviticus than the synoptic Gospels.”

He was also challenged by a larger culture — reflected by his denomination — that is predisposed to the use of military force, Parham added.

“He created a new tradition of peacemaking among Baptists, but he was never successful in moving that tradition into the mainstream of Baptist churches,” Parham said. “Peacemaking remains on the outer circle of the Baptist moral agenda.”

‘Increasing incrementally’

But there is reason to be optimistic about the present and future of Baptist peace activism, as some participants note an increasing presence of Baptists in ongoing campaigns.

The Baptist World Alliance and the Baptist Peace Fellowship continue to do excellent work while individual Baptist scholars and theologians are more and more involved in peace delegations to war-torn and hostile nations, said Jim Jennings, the founder of Conscience International and a member of First Baptist Church in Gainesville, Ga.

In January, Jennings led a delegation of American scholars to Iran for talks with Iranian academics and government officials. One of the leading American delegates was Rob Nash of Mercer University’s McAfee School of Theology.

“I think that’s increasing incrementally,” Jennings said. There will be natural limits to that increase based on the attitudes of society.

“I think that’s increasing incrementally,” Jennings said. There will be natural limits to that increase based on the attitudes of society.

“Baptists are a reflection of the political spectrum of our country — and probably in other countries as well.”

Personally, Jennings said his Baptist faith is a “100 percent” motivator of the peace and justice work he does around the world.

That work has taken him to Iran, Syria, the Sudan and Lebanon. He’s also met with “Islamic organizations that have intimidating names” to Americans.

His drive matches Stassen’s in this regard, Jennings said.

“Everything springs out of a vision of peace that when Jesus says ‘blessed are the peacemakers,’ it is incumbent on us as Christians to follow that.”

Bringing ‘real change’

Another trend some are noticing is that many Baptist peace and justice activists are flat-out exhausted, Polaski said.

That comes from years spent, domestically and internationally, combating poverty, racism, education inequality and other social ills.

“There are a lot who … are tired because they are working on issues that don’t get fixed in a lifetime,” Polaski said. “No matter how faithful you are, no matter how hard you try, you are not going to fix poverty.”

But there is a positive trend at the same time where the work by Baptists around the world are being seen to influence more positive behavior among those being helped, she added.

Those strides are made where Baptists are teaching conflict transformation skills in settings ranging from American churches to villages in Africa.

Those strides are made where Baptists are teaching conflict transformation skills in settings ranging from American churches to villages in Africa.

“Peacemakers are people who respond to inevitable conflict in ways that go deeper, in ways that bring real healing and ways that bring real change,” Polaski said.

Baptist peacemaking is moving ahead, she added.

“While some people are tired and frustrated because a lot of injustice is still out there, I also see people who are making a real difference every single day.”