I was born in the waning years of the Vietnam War. I don’t recall the war itself, but one of my earliest childhood memories dates to about 1970 and, for some reason, it is remarkably vivid.

I had tagged along with my dad to fill up the family car at Red Clark’s service station in Buford, Ga. We went inside to pay, and there was a small television above the counter near the cash register. On it was grainy, black-and-white footage of a war protest. What I remember even more than those images were the angry, hate-filled faces of a small knot of men who were standing there watching the broadcast. It would be a long while yet before I would begin to question the morality of the Vietnam War specifically, or of all war generally — my pacifism came of age with Afghanistan and Iraq, not Vietnam. I remember even then, though, being baffled as a child to learn that there was something wrong with not liking war.

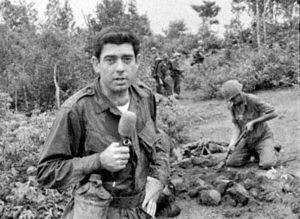

A young Dan Rather reports from Vietnam in 1966.

I’m still puzzled by that today, and I’ve long believed that we, as a nation, should have spent much more time honestly wrestling with the lessons we should have learned in Vietnam. Unfortunately, far too many of us asked the wrong questions and learned the wrong lessons.

No more Vietnams?

Like Richard Nixon, while we may have eventually come to say, “No more Vietnams,” we didn’t mean that we should never again fight such a senseless war. We meant that we should never again lose one. Rather than embracing the cold, hard truth that the Vietnam War was a blood-drenched tragedy, and letting that truth lead us to value peace over war, we let defeat become a festering wound on our national pride. A personal affront waiting to be avenged.

On April 29, 1975, a helicopter lifts off from the U.S. embassy in Saigon, Vietnam, during the evacuation of authorized personnel and civilians. More than two bitter decades of war in Vietnam ended with the last days of April 1975. (AP Photo/File)

Today, an older me watches television and again sees images of a decades-old war being lost. I see a war in Afghanistan that has been fought at a cost of $1,000,000,000,000 and that has left more than 240,000 dead, including 70,000 non-combatants. I watch a panicked evacuation of Kabul that is eerily reminiscent of news footage of Saigon in the early 1970s.

I am frankly sickened by what has been nothing less than a 20-year-long failure of our nation’s morality, reason and imagination, with administrations from both parties seemingly uniformly dedicated to repeating the Vietnam War rather than learning from it. To fully understand this current disaster of our own making, it’s important to look well past 9/11 back to 1979, and a fateful decision by the Carter administration that started us down the path to ruin in Afghanistan.

Operation Cyclone

In 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan to restore a deposed communist government. In response, the Carter administration launched “Operation Cyclone,” a CIA program that funneled covert military assistance to the mujahideen — a group of extremists with known ties to terrorism who were, nonetheless, willing to wage a guerrilla war against Soviet forces in the name of Islam. Operation Cyclone grew exponentially under a supportive Reagan administration, with the U.S. funneling more than $600 million in military aid to so-called “Afghan freedom fighters” in 1987.

President Jimmy Carter faces reporters in the White House press room on Dec. 28, 1979. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, left, and White House Press Secretary Jody Powell look on. Carter commented on the situations in Afghanistan and Iran. (AP Photo)

When the bloodied Soviet troops eventually withdrew, America seemed to lose interest in Afghanistan overnight. Almost all funding was cut off from the surviving Afghan government, and the assistance we had been providing to Pakistan to help defray the staggering costs of a flood of Afghan refugees largely dried up as well.

As early as 1990, Pakistan’s Benazir Bhutto had warned President George H.W. Bush that the U.S., through its military support of the mujahideen, was “creating a Frankenstein.” With the benefit of hindsight, we know how prophetic that warning was. We were creating a Taliban.

As bad as Operation Cyclone looks in hindsight, it was reprehensible from its start. A since-declassified Dec. 26, 1979, memorandum to President Carter from his security adviser, Zbigniew Brezinski, is one of the most disturbing government documents I’ve ever seen. In it we learn that our support of the mujahideen had nothing to do with protecting the Afghan people. It had everything to do with creating a “Soviet Vietnam” and then feeding enough weapons into Afghanistan to ensure that the war would be protracted and bloody for our Cold War foe. Shockingly, Brezinski clearly foresaw what a devastating toll such a war would take on Afghans but viewed this as a bonus for the U.S. which, by keeping its own bloody hands hidden under the table, would “be in a position to indict the Soviets for causing massive human suffering.”

Ironically, a deliberate decision was made to funnel our military aid in the Afghan/Soviet war to persons known for extremist “jihadist” views rather than the more mainstream Afghan factions who had largely borne the brunt of the defense of Afghanistan up until that point. Again, we saw such a step as politically astute in that we hoped we could reframe what had largely been seen as a political conflict up until that point into a religious holy war, with the U.S. then leveraging that impression to create hostility between the Soviets and Muslims around the globe.

“The U.S. largely created the Taliban and stoked animosities between various factions in Afghanistan by favoring some and rejecting others.”

In short, the U.S. largely created the Taliban and stoked animosities between various factions in Afghanistan by favoring some and rejecting others. We essentially trained and armed the Taliban to fight a protracted guerrilla war against an overwhelmingly superior military force, and then lost any real interest in helping a tattered and torn nation rebuild from the ruins once the war was over. We also essentially taught the Taliban how to script any opposition to its authority in religious terms, ensuring that our own troops later would be seen as crusaders, not mere soldiers, by many Muslims around the world.

Just war theory

All that aside, some Americans still would urge that our own invasion and occupation of Afghanistan from 2001 until 2021 was different from the Soviet invasion and occupation of the 1970s and 1980s. That it was moral. That it was just.

As a pacifist, it’s probably unsurprising that I don’t share those views, nor do I agree with the concept known as “just war theory,” which many Christians embrace. In fact, I think our war in Afghanistan vividly reflects why this concept is an inadequate hedge against the brutality innate in war and in each of us — a brutality that may remind us of the Emperor Constantine and his legions, but which cannot be squared with a Christ pleading for the forgiveness of his executioners while dying on a cross.

In fact, even a cursory assessment of the Afghanistan war framed in terms of some of the classical premises of just war theory reveals a dark but inescapable truth. While we are more than pleased to dress up our war-time rhetoric with the language of just war, we do not intend to be true to our own words. America is more than ready to fight even a transparently unjust war. It just doesn’t intend to admit it.

War as a matter of reluctant last resort

One of the primary principles of just war theory is that violence never can be a first response even to the worst of provocations. War must always be a last resort, one turned to reluctantly when all other paths to ending the conflict have been tried and failed. It must never be entered in haste or without deliberation.

No part of that notion holds true as to our war in Afghanistan. Exactly one week after 9/11, President George W. Bush signed into law a joint resolution of Congress affording him a broad, almost limitless, authorization for the use of force against those responsible for the terror attacks against the U.S. By Oct. 7, 2001, U.S. bombs were being dropped on Afghan soil and, less than two weeks later, U.S. ground forces were in Afghanistan.

The last thing such a timeline reflects is deliberation or hesitancy. Instead, we see almost a primal, reflexive urge to lash out in anger at those responsible for the 9/11 attacks without a fully formed understanding of whom that might be, and before we even began to grapple with the question of why they attacked us.

“We dedicated less than a month to deciding whether to commit ourselves to a war of invasion and occupation.”

Simply put, despite our own experience in Vietnam, and our front-row seat for the decade-long Soviet war in Afghanistan, we dedicated less than a month to deciding whether to commit ourselves to a war of invasion and occupation, and we spent most of our energy in that month planning the logistics of the invasion, not seeking a path to avoid it.

War as premised on a just cause with clearly defined ends

Another key premise of just war theory is that a war must be justified, and it must have clearly defined ends. It is perhaps telling in this regard that our search for some valid justification for our invasion and occupation of Afghanistan has lasted as long as the war itself.

At first, the justification offered was clear: revenge for a past wrong, and a desire to replace a hostile foreign government with one more to our choosing. Given that such a motive is wholly inconsistent with just war theory, an almost immediate pivot was made, spearheaded by Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, to recast the invasion as defensive, designed as a preemptive strike to prevent future attacks on U.S. soil.

Of course, such a spin is difficult to maintain, even for someone as gifted in that regard as Secretary Rumsfeld, unless we are equally willing to justify Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor as a preemptive measure wisely undertaken to ward off the almost certain future aggression of America’s growing Pacific fleet.

The next stopping point for attempting to justify our war in Afghanistan is one that was championed by First Lady Laura Bush in the early 2000s, where the invasion was largely recast once again, this time in humanitarian terms and, in particular, in terms of a desire to improve the lives of women who were suffering oppression under Taliban rule and to provide a more democratic way of life for all Afghans.

President George W. Bush declares the end of major combat in Iraq as he speaks aboard the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln off the California coast, on May 1, 2003. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Notably, all those incentives were fully applicable before 9/11, yet prior to that dark day we as a nation showed little to no interest in improving the daily lives of Afghans. By 2006, those justifications had largely evaporated as well, with President Bush candidly acknowledging that, while the U.S. had been prepared for nation bombing, it was “not prepared for nation building.”

At some point, almost any effort to justify our continued occupation of Afghanistan was jettisoned in favor of simply attacking those who would question that such a justification existed, charging such people with refusing to honor the sacred blood shed by American service men and women in the mountains, deserts and villages of Afghanistan.

Whatever else we say about the justification for war, it must be the reason that leads us to believe in the first instance that the shedding of blood is justified. That bloodshed cannot, itself, retroactively provide the justification. Henry Kissinger tried such a spin on the Vietnam War when he realized that the reasons offered for entering the war seemed not, in hindsight, to justify the lives lost or the money spent. In a remarkable about-face, Kissinger brazenly told Foreign Affairs in 1969 that the “commitment of 500,000 Americans has settled the issue of the importance of Vietnam.”

Simply put, we cannot make an immoral war holy by dredging our flag through the blood of the soldiers who needlessly died fighting it. To do so, and to then slur critics of the war as somehow trampling the graves of our noble war dead, is absurd, especially when those criticizing war are often the most dedicated to seeking any and all means to avoid the sacrifice of life in the first instance.

War as premised on a high likelihood of success

Retrospectively assessing the likelihood of our anticipated success in obtaining the goals of our invasion and occupation of Afghanistan is difficult at best given the ill-defined and shifting nature of those goals. It is apparent, though, that Americans have, for a long time, grossly overestimated the efficacy of warfare as a means to solving complex issues, affording almost mystical power to our bullets and bombs.

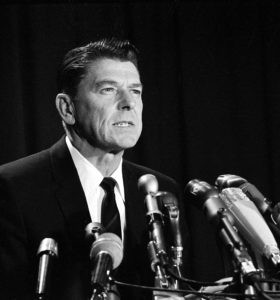

Actor Ronald Reagan answers questions at a news conference in Los Angeles, Ca., on Jan. 4, 1965, after announcing that he will campaign for the Republican nomination for governor of California. (AP Photo)

This is the hubris that would lead a young Ronald Reagan running to be governor of California to tell the Fresno Bee in October 1965 that it’s “silly talking about how many years we will have to spend in the jungles of Vietnam when we could pave the whole country and put parking stripes on it and still be home for Christmas.” It’s the same view that led Secretary Rumsfeld to blithely declare on May 1, 2003, (echoing President Bush’s “mission accomplished” declaration in Iraq) that major combat was over in Afghanistan and had achieved its end. A quick glance at Kabul in 2021 suggests that Secretary Rumsfeld was not simply premature in his pronouncement. He was horribly wrong in his understanding of what, if anything, had been accomplished by a year and a half of war.

It is clear that the U.S. has an equally pronounced tendency to grossly underestimate the effort needed to try and rebuild what has been blown apart by war. President Bush’s April 2002 speech at VMI is tragic in this regard, with the president declaring, during active combat, that by “helping to build an Afghanistan that is free of this evil (meaning the Taliban), we are working in the best traditions of George Marshall.”

Of course, Gen. Marshall knew what President Bush had not yet learned at that time. You can build with bricks and bread. You cannot build with bullets and bombs. As noted earlier, it would take President Bush four more years to realize that America was “not prepared for nation building” in Afghanistan.

In sum, even if the replacement of the Taliban government with a more democratic and open society would have been an end sufficient to justify the means of war, it is clear that we never had a plan remotely likely to succeed in that mission. Instead, we are now leaving behind an Afghanistan that is war-torn and impoverished, one that is wracked by internal strife, and one in which many of those who previously were at risk for abuse or persecution do not simply face that same risk; they also face the potentially lethal risk of being branded as “pro-American.” We’ve killed tens of thousands of innocent people and spent almost $1 trillion making Afghanistan a worse place for Afghans and leaving the region less stable than we found it.

“We’ve killed tens of thousands of innocent people and spent almost $1 trillion making Afghanistan a worse place for Afghans and leaving the region less stable than we found it.”

War as restrained by proportionality and limited to just means

Finally, just war theory teaches that any violence in war must be proportional to the violence that occasioned it, and that war must be waged in such a way as to minimize harm to non-combatants.

As candidly acknowledged by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara in a May 1967 memo to President Johnson about the Vietnam War, despite efforts to minimize war protests, it was becoming increasingly clear that there “may be a limit beyond which many Americans … will not permit the United States to go,” as the “picture of the world’s greatest superpower killing or seriously injuring 1,000 non-combatants a week, while trying to pound a tiny, backward, nation into submission on an issue whose merits are hotly disputed is not a pretty one.”

Secretary McNamara understood this. We, as a nation, apparently did not. A few horrific examples suffice. They are not as isolated as we would hope.

- In June or July 2002, an American AC-130 gunship bombed a residential area in the village of Kabrak, killing 48 non-combatants and injuring 117 more.

- In November 2008, a U.S. missile strike targeted an Afghan wedding, killing the bride and as many as 90 other innocent civilians, including a number of children.

- In October 2015, another American AC-130 gunship bombed a hospital in Kunduz, killing at least 42 non-combatants.

In terms of proportionality, it bears stressing that almost 3,000 American non-combatants tragically lost their lives in the terror attacks of 9/11. American and coalition forces have since killed more than 70,000 equally innocent Afghan non-combatants over the course of the invasion and occupation of Afghanistan.

Those losses are not simply tragic for the Afghan victims and their grieving loved ones. Consistent with Secretary McNamara’s Vietnam-era warning, such events have done serious and lasting harm to our national reputation, likely radicalizing future anti-American terrorists much more effectively than our enemies could have hoped to accomplish on their own. Or as stated by General Stanley McChrystal from Afghanistan as early as 2008, “We must avoid the loop of winning tactical victories, but suffering strategic defeats, by causing civilian casualties or excess damage and thus alienating the (Afghan) people.”

Again, these voices largely went unheard, with President Trump speaking to our troops at Arlington, Va., in August 2017, responding to U.N. reports of a noteworthy surge in Afghan civilian casualties caused by U.S. and coalition airstrikes by promising to further loosen restraints that were designed to protect against such atrocities, but which President Trump viewed as unnecessarily handcuffing our war effort.

We are now at the end of America’s direct combat engagement in Afghanistan, although the almost unimaginable damage done by 20 years of war will long remain. To be the rare Southerner willing to borrow from Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, war is never just. War is hell.

I pray that we learn that lesson now, but I fear that we will not. I’m just no longer sure how much more blood will have to be shed before we take Christ at his word and come to see that those who live by the sword will die by it.

Chris Conley

Chris Conley is an attorney and graduate of the University of Georgia and of the Emory University School of Law. He and his wife, Mary, live in Athens, Ga., where both are members and deacons at First Baptist Church. They have one son, Aaron, who also is an attorney, and a miniature schnauzer, Oso, whose career path remains uncertain.

Related articles:

Blame me for the situation in Afghanistan | Opinion by Craig Nash

Will U.S. departure from Afghanistan create a humanitarian and religious freedom crisis?

Reflecting on the effects of 9/11 and the disarray of America foreign policy | Opinion by David Gushee