I have been working to free Curtis Flowers for 12 years. He’s been locked up twice that long.

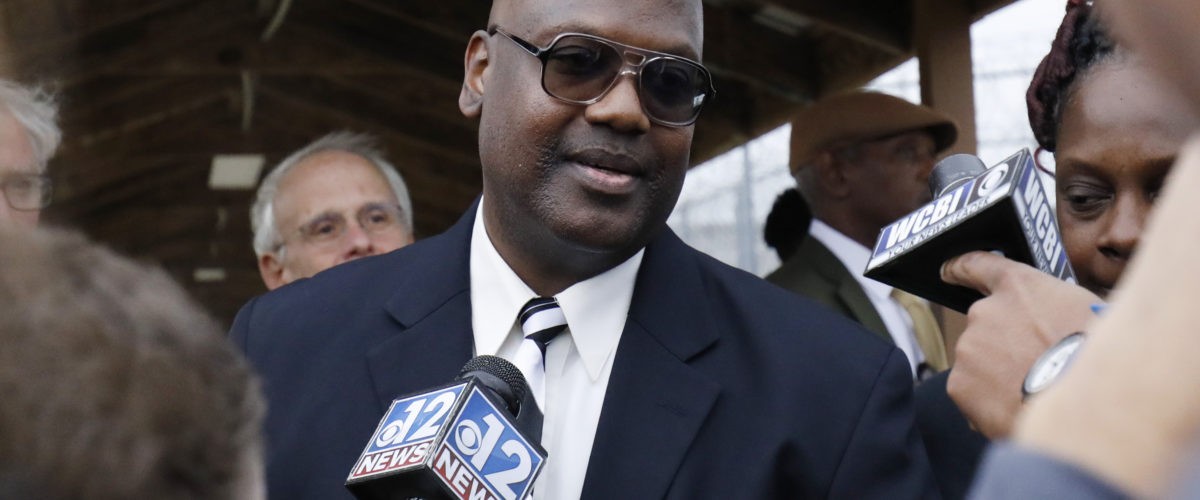

Yesterday, Sept. 4, after six flawed murder trials, Lynn Fitch, attorney general of Mississippi, dismissed the charges against Curtis with prejudice. That means the state can’t indict him a seventh time.

Alan Bean

Twenty-three years after being wrongly arrested for a brutal quadruple murder, Curtis Flowers is free.

Viewed through a lens of justice, we may wonder why it took so long for a case this weak to unravel. But when you understand how hard it is to vacate a death sentence, the attorney general’s decision feels like a miracle.

I was speaking to a legal conference in New Orleans about my advocacy work with Friends of Justice when I first learned of the Flowers saga. Ray Carter, Flowers’ lead attorney, told me his client had been to trial five times on the same charges. The crime took place in Winona, Miss., the town where Fannie Lou Hamer, the civil rights icon, was beaten half to death in 1963. A sixth trial, Carter told me, was scheduled for June 2010.

A week later, I was in Winona, visiting with Curtis’ parents, Archie and Lola Flowers. They introduced me to friends and family members, who told me all the reasons why Curtis was an innocent man.

They showed me the furniture store where four innocent people had been murdered execution-style early one June morning in 1996.

I talked to two people who had been questioned by the local police. They were shown a handbill offering a $30,000 reward for information leading to a final conviction. Then they were shown a picture of Curtis Flowers. All they had to do was say they saw Curtis, at a particular place and time, on the morning of the crime.

The folks I talked to refused to take the bait. Others were not so principled. Once they signed a statement, they were informed that they would be subpoenaed to testify and that the penalty for perjury was severe.

“No one personally acquainted with the soft-spoken gospel singer believed he was capable of murder.”

District Attorney Doug Evans transformed these isolated bits of testimony into the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. No single witness saw Curtis do the deed, but the state used the words of these supposed witnesses to trace the suspect’s journey from his duplex apartment to the scene of the crime and back again.

In Winona’s Black community, these witnesses never were taken seriously. No one personally acquainted with the soft-spoken gospel singer believed he was capable of murder.

“I’ve worked in this jail a long time,” a prison guard told me, “and I can tell you one thing: Curtis doesn’t belong in here. He is kind, compassionate, helpful and always respectful. Curtis Flowers,” the man told me, “is the finest young man that ever put on a pair of pants.”

White residents didn’t think Curtis was guilty; they knew he was guilty. Sure, the case was circumstantial, but they believed the witnesses DA Evans assembled. Curtis had to be guilty, the reasoning went, because the crime was so heinous. If Curtis wasn’t the killer, it was likely that the crime never would be solved. That was unthinkable. Somebody had to pay.

When I arrived in Winona for trial number six, the atmosphere was electric. I was accompanied by my daughter, Lydia Bean, and Liliana Ibarra, a young woman from Boston who had participated in our fight for justice in Tulia, Texas, a decade earlier. Once white residents saw us sitting on the Black side of the courtroom, they immediately became suspicious. The father of one of the victims confronted me in front of the courthouse and suggested I was having improper relations with Lydia and Liliana. Anybody who believed that Flowers was innocent, he said, was either drunk or stupid, and he didn’t think I had been drinking.

Evans always had been able to get easy guilty verdicts from all-white juries. But since Winona is half Black, Evans couldn’t get a monochrome jury without revealing his racial bias. When racially diverse juries were selected, they split along racial lines.

Over the years, I have dedicated more than 40 blog posts to the Flower case, paying particular attention to the fraught racial history of the region.

“Whites were afraid their “Southern way of life” was under assault. Blacks learned that challenging the Southern way of life could get you fired or even land you in an early grave.”

Gradually, I began to understand the fear. Whites were afraid their “Southern way of life” was under assault. Blacks learned that challenging the Southern way of life could get you fired or even land you in an early grave.

Every time Curtis went to trial, the fear in Winona was palpable. Everyone in the white community was close to one or more of the murder victims, and every new trial forced them to relive the horror.

Black residents lived in fear that an innocent man would be condemned to death.

We stayed with Archie and Lola through a trial that stretched over a week and a half. When the death sentence was announced, Archie and Lola left the courtroom with quiet dignity. This wasn’t their first rodeo.

We all believed justice was coming. We didn’t realize it would take another 10 years.

When Mississippi’s highest court upheld the conviction, the case moved to the federal level. It is almost impossible to get a case before the Supreme Court, but this was not a typical case. And Curtis had excellent legal representation.

The big break came on May 3, 2017, when I got an email from Madeleine Baran with the In the Dark podcast. “I came across your website while researching,” Madeleine told me, “and I’d like to learn more about the Flowers case.” Two weeks later, Baran arrived at my doorstep accompanied by her producer, Samara Freemark. They had read every word I had written and spent two full days peppering me with questions.

In the Dark planned to spend a full year in Winona doing interviews, sifting through documentary evidence and asking hard questions.

Over the past three years, they have produced 19 episodes dedicated exclusively to the Flowers case. Working from my blueprint, they took the inquiry to the next level. Soon they had millions of devoted listeners. Witnesses began recanting. DA Evans was being deluged with letters demanding that he drop the charges against Curtis.

Nine years after the somber conclusion to trial six, the Supreme Court vacated the conviction due to racial bias in jury selection. But the 7-2 ruling suggested that the justices had been listening to In the Dark and reading my posts. The case was sent back to the court in Winona. Judge Joseph Loper, who had experienced a surprising change of heart, released Curtis on bail.

Finally, nine months later, we received the joyous news.

It is easy to blame this travesty on a single prosecutor from Mississippi. That would be a mistake. The brand of racism at work in this case is systemic. People believed Flowers was guilty for the same reason they believe in conspiracy theories like QAnon. Those who fear their cherished way of life is in jeopardy are predisposed to trust authority figures who embody their fear.

Curtis Flowers is in no mood to give interviews. Not yet. But in a brief statement released the day of his liberation, he said that what happened to him is happening throughout Mississippi and across America.

Tragically, he’s right.

Alan Bean is executive director of Friends of Justice, an alliance of community members that advocates for criminal justice reform. He lives in Arlington, Texas.

Related articles:

Curtis Flowers was tried 6 times for the same crime. His story reveals 3 kinds of Christians