Michael Gungor

By Alan Bean

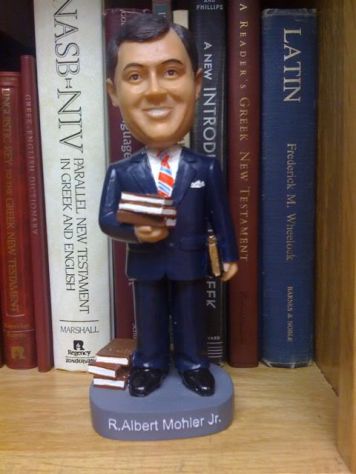

Al Mohler has adapted nicely to our twenty-first century media revolution. He even doespodcasts.

Al isn’t hip. Not even a little bit. But he talks about hip people, albeit with disapproval.

I can’t imagine the venerable Roy Lee Honeycutt or Duke McCall (Al’s predecessors at the helm of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky) dissecting the theological errors of pop artists, but Al is willing to have a go.

Take Gungor, for instance.

Who, or what, is “Gungor” you ask.

First, Gungor is a guy (Michael Gungor) and second, Gungor is the musical ensemble Michael formed with his wife, Lisa, and a few others. The couple moved to Denver in 2007 and started a church for creative types like themselves. If you want a taste of their music, here’s a taste:

According to Wikipedia, the album and the song “Beautiful things” (released in 2011) “were nominated for the Grammy categories Best Rock or Rap Gospel Album and Best Gospel Song, respectively.” Relevant, a magazine for hip young Christians, has produced a number of YouTube videos if you want to hear more.

The lyrics to “Beautiful Things,” reveals the wistful, longing, questing tone of Gungor’s music.

All this pain

I wonder if I’ll ever find my way

I wonder if my life could really change at all

All this earth

Could all that is lost ever be found

Could a garden come up from this ground at allYou make beautiful things

You make beautiful things out of the dust

You make beautiful things

You make beautiful things out of us

Michael Gungor is an evangelical Christian . . . of sorts. He loves Jesus and doesn’t think it’s much of a stretch to believe that Jesus turned water into wine or healed the sick. In other words, he’s no hard-science rationalist.

But, like millions of young, educated Christians his age (he was born in 1980), Michael Gungor has thought long and hard about the Bible and has reached some tough conclusions.

Specifically, he doesn’t think he can hold onto Jesus without relaxing his grip on some of the Bible’s nasty bits. You know, the smitings and blood-soaked massacres that God commands, or the notion that the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ would sweep away thousands of innocent people in a flood that covered the highest mountains.

It isn’t just that Noah’s flood is hard to reconcile with the universal consensus of the scientific community; it’s also hard to square with the compassion and infinite forgiveness of Jesus. If the man from Nazareth truly is the human face of God, there’s a disconnect here.

And then there’s the fact that the early chapters of the Bible (what C.S .Lewis called “the parables of Genesis”) read like ancient folk tales or “myths”. They aren’t mythical in the sense that they aren’t so; but they are much closer to poetry than prose.

When Gungor sings “you make beautiful things, you make beautiful things out of dust,” he is affirming the God of the Apostle’s Creed: the “Maker of heaven and earth.”

But if you ask how God made the world and all that dwells therein, Gungor would direct you to the scientists (who are making shocking discoveries about the wonders of God’s creation on a daily basis) and to poets who reckon with the wonder the rocks and skeletons reveal.

Al Mohler is not impressed. There is a biblical worldview and a scientific world view, he says, and we must decide which has the upper hand. Mohler isn’t anti-science, but when scientific consensus and the revealed, inerrant, infallible Word of God are at odds, Christians go with the Good Book. Every time. Simple as that.

We know the Bible is true, Al says, because it is the very Word of God, and God doesn’t lie. We know the Bible is the Word of God because the Bible itself says so.

When Michael Gungor accepts the miracles of Jesus while questioning the historicity (and the ethical implications) of Noah’s flood, Mohler accuses him of arbitrary and illogical thinking. Dispense with an inerrant Bible, Al says, and you have no philosophical foundation for accepting anything the Bible says.

All or nothing at all.

Mohler doesn’t argue that the Biblical worldview is demonstrably superior to the scientific alternative. He’s a “presuppositionalist” who believes our fundamental, a prioriassumptions predetermine our conclusions. Start with God’s word and you get a biblical worldview; start with science, and you get a scientific worldview. Small wonder that the God of the Bible and the men in lab coats sometimes disagree, and when they do, eternal destiny hangs in the balance.

Mohler doesn’t argue with scientists, or the vast majority of theologians and biblical scholars who claim to be cool with science. These people don’t pay his bills. Al’s bills are paid by simple folk who love God and have never been forced to grapple with the theological implications of the scientific method.

A quarter of the American population believes the sun revolves around the earth, so Al has a considerable constituency.

I’m not saying that Al Mohler is simple, or that he’s a con man sayin’ what he knows ain’t so. His theology is what happens when you spend a quarter century in an environment where no one is allowed to consider alternatives to “the biblical worldview”.

Most of us don’t live in that world. Like Michael Gungor, we want it all: the Bible, the poets, and the best science our little minds can grasp.

Like Gungor’s song, our pendulum swings between “Could a garden come up from this ground at all?” and “you make things beautiful!” We want to hold the anguished question and the ringing affirmation in holy tension.

If Al Mohler’s logic works for you, that’s fine. If you are young, restless and reformed, go for it. By all means.

But millions of young people aren’t prepared to choose between secular scholarship and the Bible. The crisis might come in high school, or it may wait until college; but sooner or later, our sons and daughters confront questions about God, faith and the Bible that never came up in Sunday School and were never addressed from the pulpit. Convinced that the Church has no answers, they are walking away, millions of them, and they’re not coming back.

Al Mohler has nothing to say to these kids; he might as well be speaking in tongues.

But some of them will listen to Gungor.

I hope they do. But pop singers, however gifted, can’t do the heavy theological lifting for the church.

Al Mohler has a point, after all. It isn’t hard to find churches that have abandoned their erstwhile allegiance to an inerrant Bible and Four-Spiritual-Laws evangelism, but what do they offer as a substitute?

Thin gruel, mostly.

Typically, denominational training materials avoid hard questions that easily translate into controversy and cancelled orders.

The adult Sunday school classes created for the rebels and eggheads drift from “The Gnostic Gospels”, to “Zealot: the Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth”, to the latest self-help guide for the spiritually inclined.

It’s all great fun, but such classes rarely coalesce around a gospel consensus; a few hearty conclusions about how Jesus impacts life in the real world. The traditional language of faith no longer speaks to us and we have little to put in its place.

And Al Mohler is right about the need to make fundamental choices. But the question isn’t whether or not we take the scientists seriously. God wants to know if we take Jesus seriously.

Do we?

We need a new orthodoxy

. . . that begins and ends with Jesus and the kingdom he proclaimed

. . . that values truth wherever it is found

. . . that is simple, honest and humble.

Michael Gungor may not have all the answers we seek; but he shows us how to ask the right questions.