Kathy Manis Findley made a career pursuing justice as a Baptist minister, and she is up to it again with a virtual watercolor exhibit offered as both a clarion call and lament for racial inequity in a time of pestilence.

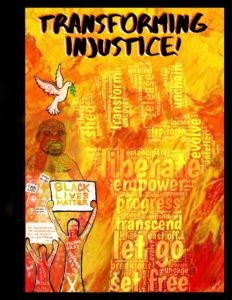

Hosted online by the Alliance of Baptists, “Transforming Injustice!” presents five paintings accompanied by narrative meditations intended to draw attention to police and cultural violence against African Americans.

Kathy Manis Findley

The inspiration for the series came as she attended the Alliance’s Juneteenth Vigil online. At one point, participants were asked to state their commitment to opposing injustice.

“Immediately my mind jumped to the word ‘transformation’ because everything we’re doing and everything going on is not going to be the change agent,” she said. “It is going to have to be a transformation of society and experiencing of the gospel of Jesus Christ in new ways.”

Manis Findley has experience in the area of compassion and striving for racial equity. She has served as a hospital chaplain, pastor, worship minister, trauma specialist and leader of a nonprofit for domestic violence and abuse victims.

She also raised a Black son, which influenced her watercolor exhibit.

“Being his mother, even being white, it immerses me in the Black culture and the Black lament and the Black longing for a new day,” she said. “It was definitely a catalyst in helping me to move on with the paintings.”

In the text that accompanies the series, Manis Findley explains that concern for society’s powerless always has been part of her makeup.

“My quest at times led me to fight for justice for women, for victims of abuse, for prisoners, for Black and brown persons, for immigrants, for the poor, for LGBTQ persons,” she wrote.

“My quest at times led me to fight for justice for women, for victims of abuse, for prisoners, for Black and brown persons, for immigrants, for the poor, for LGBTQ persons,” she wrote.

Manis Findley also is an author and avid blogger now retired from active ministry. She spoke with Baptist News Global about how the development of her calling led her to the fight against injustice.

You’re a retired Baptist minister. How and when did you sense your calling?

I always was a religious girl, but I was a Greek Orthodox little girl. When I was 17, I became a Baptist quite by accident. I always felt a calling, although at 17 I had no idea that a woman could be a minister. It really evolved when my husband and I returned from the mission field — we served in Uganda with the (SBC) Foreign Mission Board. It was difficult because my husband went to be a church pastor and I had no idea what to do. I had no identity. But I knew I had this calling in my heart. So, eventually I became a hospital chaplain. And it was during that four years that my calling solidified, and I understood that I was indeed called to ministry. I later served as the pastor of Providence Baptist Church in Little Rock.

I have to ask: how did you become Baptist “by accident?”

Our family moved to a very small town in Alabama where there was no Greek Orthodox church. So, I started going to church with my friends and, as you can imagine, most of them were Baptist. I joined the choir. I was active in Sunday school. One day the pastor asked me if I was a Christian. And I said, “Oh, yes.” He then asked if I had formally accepted Jesus Christ as my Savior. I said I was baptized as a baby and he said, “That won’t do.” So, I professed Jesus Christ as my Savior. They made a countywide youth rally on the night I was baptized. I had to get up with wet hair and give my testimony.

How did painting enter the picture for you?

My last ministry position was at New Millennium Church in Little Rock, where Wendell Griffen is the pastor. It was my first time serving in a predominantly Black church, and they called me to be their minister of worship. It provided me a great exposure to another culture. I had experienced that culture as the mother of a Black son. I was exposed to the difficulties of systemic racism. But going to New Millennium just opened my eyes.

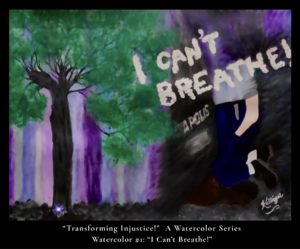

Watercolor #1, “I Can’t Breathe.” (Images/Courtesy of Kathy Manis Findley).

Unfortunately, that ministry was cut short because I got very sick with end-stage kidney disease. Because of my illness, we moved to Macon, Ga., in 2015 to be close to family and that was my forced retirement. And I grieved so much about leaving New Millennium that for a while I was in this dark hole. In the meantime, I started doing art. I never did art until I moved to Macon, and I was so bored I started doing watercolors.

How did the painting help you?

I became immersed in the watercolors. I became almost obsessed with painting. I painted so many things: animals, women in community, a flower, landscapes. But the watercolors in this series are completely different from any of my earlier paintings. I really struggled with that series. It almost put me in a place of lament. Not just doing them, but all the things that were happening, George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery and on and on. It manifested itself in a season of lament.

What was it that struck you so powerfully during the Alliance virtual gathering? Did something just click?

Watercolor #5, “Lift Hope High!”

Yes, absolutely. It was just a normal vigil on Juneteenth. It was lovely, the presentations and the music. At the end there was a call to prayer, and they read the names of probably every single person in the current movement who had been victims of police violence. I heard the names a thousand times but there was something so powerful about being in the midst of COVID-19 and sensing this feeling of beloved community on Zoom. At the end of the whole thing they asked us to share through chat what would be our personal commitment to transforming injustice and working against systemic racism. So, I wrote down, “I am going to do a series of watercolors titled ‘Transforming Injustice.’” I really didn’t know where that came from. I can’t help but believe it was a God thing.

That was in June and the Alliance posted your exhibit earlier this month. How did you get all that painting and writing finished so soon?

There was urgency. There was anger. And above all there was lament and fear. I am afraid for my Black son and my grandchildren. Yes, urgency is the word for it. I put my nose to the grindstone and immersed myself in these watercolors. And they are so different from my other paintings that I had to write a narrative around them. A meditational moment follows each watercolor. I hope this is how people will use this: reflect on the art, look at the brief narrative with each piece, and go through the lament and the questions and the prayer at the end. And stop. Just take it in.

The images are dark both in terms of the colors used and subject matter. What should people take from that?

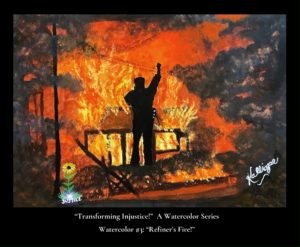

Watercolor #3, “Refiner’s Fire.”

I meant for them to see darkness, but if you notice, in each one there is also a light in there. A tiny light. And that is hope. It’s a very tiny spot in that dark image, but it’s there. And here’s the deal: I don’t do dark images. Very seldom do I do dark images. I decided from the onset the series had to be dark because this is a dark time for our nation with everything from Black Lives Matters, the death of (U.S. Rep.) John Lewis, the pandemic, and this president and the hateful inhumanity that comes from him.

Describe the emotional toll of painting one image after another like that.

It was grueling to me. That’s one reason why I finished so fast. It was painful, and I had made a commitment I considered to be sacred in the Zoom meeting. I would have to paint for a little while and stop. And that’s another place the narrative came from. I could get away from the painting for a while and write the narrative. That was very helpful.

In what ways do you see yourself continuing the work of transforming injustice?

In several ways. One is I want to present these watercolors to Sunday school classes and worship services. I want people to use the series in their churches and feel free to consult with me. I want to connect, if possible, with a congregation, perhaps in Zoom interviews or in personal reflections. The virus has opened us up to Zoom and all these other platforms and makes it possible to disseminate this series.

Churches interested in displaying the “Transforming Injustice!” watercolor series may contact Manis Findley at [email protected].