There is no doubt that Amanda Held Opelt resembles her sister, Rachel Held Evans.

Rachel, who tragically and suddenly died in 2019, was in some ways far different than her sister, yet there are striking similarities. Both have approached questions they wrestled with using similar strategies, and both have a knack for challenging their audiences.

“There always will be a connection, and, honestly, I think my dad would say Rachel and I are very different,” Amanda said in a recent interview with BNG.

Rachel Held Evans was a popular Christian columnist, blogger and author. Her book A Year of Biblical Womanhood was a New York Times bestseller in e-book nonfiction, and Searching for Sunday was a New York Times bestseller nonfiction paperback. She died May 4, 2019, after an allergic reaction to a medication.

Opelt is an author, speaker and songwriter who focuses on faith, grief and creativity.

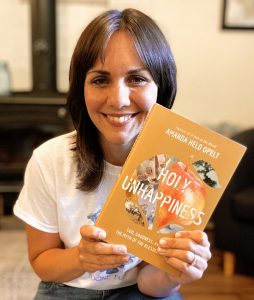

Amanda Held Opelt

“One of the biggest differences between she and I is she is a person who is very convicted and precise about her convictions,” her sister said. “I am the kind of person who can see things from multiple sides. … If you’re going to put it negatively, you might say I waffle; maybe my convictions meander a bit. If you were to put a positive spin on it, I tend to be a good liaison or advocate of different sides, because I do kind of see everyone’s perspective and have maybe empathy for where they’re coming from. I’m very curious and also maybe softer than my sister at times.”

That curiosity led Opelt to do something she and her sister also have in common —putting pen to paper. In Opelt’s new book, Holy Unhappiness, she navigates through the questions and issues faced by many young evangelicals among whom she has ministered.

“I wrote it for young adult Christians who were highly altruistic, motivated,” Opelt explaied. “They were bent toward adventure but bent toward ministry.”

Opelt understands people’s perceptions of both adventure and ministry do not always match reality. Many young adults “have a lot expectations about what their lives were going to be like in service to the Lord. My work was to provide staff care for humanitarian aid workers, and so I was the person who they dumped all their problems on. I would go to the field offices and do these kind of morale assessments and connect them to clinical counselors, but I was the person who they would go to coffee with and say, ‘This isn’t what I thought it would be.’ ‘I’m bored.’ ‘Why am I not married yet?’ Or ‘I’m married and my marriage is falling apart.’”

Opelt noticed the ideals of adventurous ministry changed as young Christians “would bump up into the reality of life. After years of having these kinds of conversations of people — very well-meaning, driven Christian people — who ticked all the right boxes and made all the good decisions to live a life in service of the Lord, … they were struggling just with life.”

Opelt has worked for a few humanitarian organizations, including Samaritan’s Purse, and she has found herself counseling and helping young adults understand God is present amid their struggles. She has learned many of these young adults bought into a dream of reality that may not be what God desires or intends.

So, perhaps much like her sister might have done, Opelt called out influencers — particularly Donald Miller and Rachel Hollins — whom she saw as strong determining voices in the lives of these young people.

“I did feel a need to maybe reference a couple of voices that were having significant influence, just in our brain,” she said. “And it’s not that everything they said or did was wrong, but it creates these narratives that they helped construct for us in our mind, on what our lives would be like. So, I thought it was needed to reference a few of these influencers who many people are listening to regarding the life that they should have of adventure.”

Opelt clarifies that most of life is spent doing normal stuff and enjoying things everyone takes for granted, like eating and enjoying a good piece of fruit. Although those simple joys may not seem adventurous, they are just as good and worthy to pursue, she believes, and can bring adventure and joy into life.

“We’ve been given this idea that you kind of measure the success of your life based on its excitement,” she explained. “I think it’s Andy Crouch who talks about impact fetish — I love that term — this kind of preoccupation we have with adventure, impact and excitement. Sometimes that’s about God; however sometimes it’s about us. Sometimes it’s our fear of boredom; it’s our fear of anonymity.

“The thing most people are afraid of is just disappearing or just not being known or not being seen, not being noticed.”

“In a hyper-individualized culture — show-boasting kind of culture, a culture where we’re all kind of exhibitionists online to some degree — the thing most people are afraid of is just disappearing or just not being known or not being seen, not being noticed. I think the Bible speaks to that in a million different ways, but we have to extract ourselves from this kind of hyper-individualized Western exhibitionist culture.”

She added: “I immediately try to check myself and say, ‘What is this? What is this in you that needs to be seen and known and noticed?’ This is kind of a post-Enlightenment phenomenon of like, we are now no longer satisfied with an ordinary station in life or the station of our birth. (We’re hooked on) climbing that ladder of accomplishment, of notoriety, of achievement. And it’s in most of us, which is why we just have to constantly be pushing back against these things and noticing them, and knowing that Christ is enough.”

Although Opelt and her sister present their convictions about how Christ followers should live out their lives differently, both have displayed the conviction and courage to challenge their audiences. Oplet’s focus most often has been stressing the value of contentment so people will understand that ordinary and normal are OK with God, who is more than enough.

“It was deconstructing years and years of expectations of what the good life should feel like, what the blessed life should feel like,” she said. “I just think we have to shift the things we find joy and happiness in and shift those expectations of what true blessing really is. The sabbath ultimately is about resting in your identity: That you are good, and you are loved, and you are wonderfully made just by virtue of being a child of God. You do not have to strive; you do not have to hustle. You are made in the image of God, and your goodness has been accomplished by Christ. We’re not slaves to Egypt. We’re not slaves to our culture’s expectations. We’re not slaves to the opinions of other people. We are children of God, and he has said it. And we can rest in that, and we can rejoice in it.”