So many of us look at America’s religious, political and racial landscape and wonder what on earth has happened. How is it possible that American evangelical Christians, who once insisted moral fitness matters, could vote for a creature such as Donald Trump? How is it possible that, as Russell Moore told NPR, American Christians could reach a point where they regard the justice teachings of Jesus as “woke”?

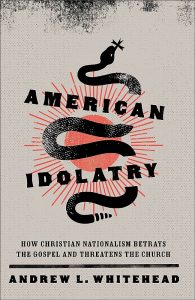

Sociologist Andrew Whitehead — who earned his Ph.D. at Baylor University and serves as associate professor of sociology at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis — has been thinking about these tensions for some time, both professionally and personally. In his brilliant but accessible new book American Idolatry, he uses his skills as a researcher and his identity as a person of faith to lean into some answers to these questions. I am grateful to Andrew for his essential work and for this conversation.

Greg Garrett

Greg Garrett: Andrew, you say you wrote American Idolatry for fellow Christians, maybe fellow evangelicals, and your appeals to the Scripture for authority make supreme sense in that context. What kind of reaction have you gotten from conservative evangelicals to the book? Are they open to hearing these hard truths through a religious lens? Have you heard from any people outside a formal faith tradition who’ve had a response to the book?

Andrew Whitehead: You’re correct, my goal for the book was to reach an audience similar to the community I grew up in and those congregations and communities I spent time in through college and graduate school. The authority of Scripture was paramount, and a commitment to the Christian faith as we understood it was central to how we organized our lives.

“I’m encouraged that there are conservative evangelicals who are reading and interacting with the book.”

I’m encouraged that there are conservative evangelicals who are reading and interacting with the book. One of the first things they might say is, “I know we likely vote differently, but I really wanted to understand where you are coming from because I do see issues with demands for Christianity to dominate American public life.”

I remain committed to seeing every person as on a journey and meeting them wherever they are. Hopefully, American Idolatry can serve as a resource that encourages them along and away from an expression of Christianity inherent to Christian nationalism that idolizes power, fear and violence and toward expressions of Christianity that align with what Jesus claimed he came to do in Luke 4 (Jesus’ inaugural address at the beginning of his ministry).

And yes, I have heard from folks outside a formal faith tradition who have read the book. I am encouraged that they find it useful for better understanding Christian nationalism and thinking through how to encourage Christians in their lives to confront it and move toward alternative expressions of the Christian faith.

GG: Growing up in our respective evangelical traditions, neither of us heard a sermon on racial injustice. One of the goals of my grant work on race funded by the Baugh Foundation is to work with pastors from a sin/grace/salvation tradition of preaching to start seeing and sharing how the Bible calls upon us to fight injustice. What advice would you have to preachers of any tradition who want to call out Christian nationalism and reach out to the marginalized?

“Reading and listening to voices who differ from you in life experiences is so important.”

AW: Reading and listening to voices who differ from you in life experiences is so important. Only when we read and empathize with the life and faith experiences of those who have had to face dramatically different challenges can we begin to learn and realize the Christian faith is not just limited to individual sin/grace/salvation. Rather, the gospel has something to say about both our personal brokenness and the collective brokenness that surrounds us in our communities and the social systems that organize our collective lives.

Our brothers and sisters on the margins have an acute and clear understanding of the second part, and those of us who are relatively privileged must listen to and learn from them if we are going to join the work of the kingdom, which Jesus taught us to pray for “here on earth as it is in heaven.”

GG: Like our friend Robert P. Jones, you’re a sociologist, and like him, you join your personal story with your research in building your case against white Christian nationalism in this book. Can you talk a little about the way you used both scholarship and lived experience to compose American Idolatry?

GG: Like our friend Robert P. Jones, you’re a sociologist, and like him, you join your personal story with your research in building your case against white Christian nationalism in this book. Can you talk a little about the way you used both scholarship and lived experience to compose American Idolatry?

AW: My professional journey as a social scientist is fundamentally shaped by my personal faith journey, and vice versa. As I looked back over my work in peer-reviewed outlets and in Taking America Back for God, I wanted to further help translate and connect this work for folks still in the congregations and communities I’d grown up in. When Brazos Press reached out about writing a book aimed at this audience, I originally passed. I wasn’t sure if I really had the answers.

But then I realized it is more about sharing my journey and giving voice to what I’ve learned and where I’m going, then inviting people to join me on that journey, wherever they might find themselves. Social science is such a wonderful tool for helping us clearly see what is happening around us. It is then up to us to take that information and collectively move toward a future that encourages the common good. It’s that work that I am committed to.

GG: One of your primary points in American Idolatry is that American Christians ought to be pursuing “kingdom power” instead of political power, and yet the exact opposite seems to be happening. Why do you think so many people who identify as Christian are turning their backs on Christian teachings — and what remedies do you see for this tragic failure? What would kingdom power look like in today’s context?

“We were told over and over that the only way to be a morally upright American citizen was to vote for a particular political party to ensure our chosen and specific ‘moral issues.’”

AW: The reason so many American Christians are committed to idolizing self-interested power, power that only serves “us,” is that we’ve been taught and discipled to see that route as a faithful expression of the Christian faith. We were told over and over that the only way to be a morally upright American citizen was to vote for a particular political party to ensure our chosen and specific “moral issues” — like abortion or homosexuality — were front and center in the culture wars, and to ignore other issues — like racial injustice — as merely “politics.”

We were taught this was the route to living according to God’s law. And it is the taken-for-grantedness of this particular expression of the Christian faith — one committed to culture warring and gaining and protecting privileged access to power — that makes it so powerful.

We remedy the situation by gently but firmly pushing back on the narrative that this particular expression of Christianity is the only faithful expression. We need to faithfully engage with the tragic portions of our history, where Christians were committed to marginalizing and destroying various communities to maintain power. We need to disciple ourselves toward different expressions of the Christian faith, ones focused on a fuller representation of the gospel as Jesus preached in Luke 4, one that is literally good news for the poor, freedom for the prisoners, healing for the sick, freedom for the oppressed and the year of the Lord’s favor.

In this sense, kingdom power is then focused on the collective flourishing of all people, not just “us.” It pushes for society to be organized so all have access to the benefits only the privileged have so far enjoyed.

GG: You and I are straight white middle-class American Christian men, and people like us have consolidated power, built hierarchies in the church and in the culture, and actively failed to confront the injustice that has benefited us. For white Christians seeking to do better, who are some of the writers, scholars and theologians they ought to read to establish the facts and resolve to confront our history?

AW: There are so many amazing writers and scholars and theologians I cite throughout American Idolatry. Those and others have been instrumental to my journey. I would encourage folks to adopt a broad rule: Read at least one book a month by someone who differs from you in at least one, and ideally two, ways.

So for me, a white, middle-class, able-bodied, straight, Protestant man, I need to read books by folks who differ from me on those descriptors. Listening and learning from folks different from us help us to see how American life and the social realities surrounding us operate differently depending on our embodied selves.

My hope is that we will then be motivated to work toward a future where all can flourish. It is this work Jesus called us toward. My hope is we begin to answer that call.

Greg Garrett teaches creative writing, film, literature and theology classes at Baylor University. He is the author of two dozen books of fiction, nonfiction, memoir and translation, including the critically acclaimed novels Free Bird, Cycling, Shame and The Prodigal. His latest novel is Bastille Day. He is one of America’s leading voices on religion and culture. Two of his recent nonfiction books are In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett and A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. He is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

Related articles:

American Idolatry: How Christian nationalism betrays the gospel and threatens the church | Opinion by Robert P. Jones

Attacks on Critical Race Theory didn’t come out of nowhere, panelists say