Two months have passed since the world watched George Floyd die under the knee of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin. In that two months, United Methodist bishops have mounted an initiative echoing the Black Lives Matter movement that they call “Dismantling Racism: Pressing on to Freedom.”

United Methodists are known for launching projects, programs and initiatives that begin with a bang and end with a whimper, but Dismantling Racism already has achieved one objective: it has forced United Methodists to confront their own institutionalized racism.

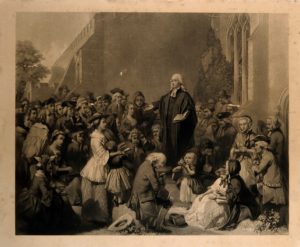

Engraving showing John Wesley preaching outside a church. (Wikicommons)

Methodism emigrated to America with colonists from John Wesley’s England. Whereas Wesley spoke out against slavery in his waning years, Methodists in the American colonies embraced it. Slavery was a profitable institution for both North and South, since the North trafficked in the Black Africans that the South purchased. Wesley inveighed against the practice in a pamphlet, “Thoughts Upon Slavery,” calling it “barbarous” and denying that slavery was needed to build the colonies’ economy. Methodism’s founder appealed to those involved in slavery to quit, invoking everything from God’s wrathful judgment at injustice to sympathy for the Africans’ plight.

Colonial Methodists paid their founder no heed.

Black slaves began to gravitate toward Wesley’s theology of God’s grace, often through the efforts of “Black Harry” Hosier, a freedman and preacher of such eloquence that he often outdrew crowds compared to his traveling companion, Francis Asbury, the first bishop of American Methodism. Despite the hundreds of souls — Black and white — brought to salvation through Black Harry’s preaching, American Methodists still practiced discrimination in their church institution.

Three episodes stand out in the United Methodist Church’s racist history:

- In 1816, discrimination in receiving the Lord’s Supper caused a group of Black members led by Richard Allen to leave St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia to form the African Methodist Episcopal Church. This was the first of today’s historically Black denominations including the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Zion, and the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church.

- In 1844, the white Methodist Church split into southern and northern branches because a bishop, James Osgood Andrew, refused to give up his slaves. This split wasn’t resolved until 1939 when three predominantly white Methodist branches reunited into a single Methodist church. The price of this merger, however, was the southern branch’s insistence on the creation of a racially segregated unit called the Central Jurisdiction to which all Black clergy and churches were assigned.

- In 1968, today’s United Methodist Church was formed through the merger of the Methodist Church and the Evangelical United Brethren Church, spiritual descendants of German-speaking colonial-era Methodists. In a reversal of fortune, the historically abolitionist EUB’s price of merger was the dismantling of the racially segregated Central Jurisdiction. This action was met with jubilation among Black Methodists and with dismay and outright anger among remnants of the former southern branch. A few dozen congregations exercised their option to leave the new denomination because of it, joining the more theologically conservative Wesleyan Church or even the Southern Methodist Church, which advocated racial separation as part of its doctrine.

Tellingly, today only United Methodists with a deep education in the church’s history know its full racist background. While it hasn’t been kept secret, neither has the UMC’s past been a priority in membership education. That’s why the past two months of activism have been a shock to some United Methodists: they had at best a vague idea of what had gone before in the church’s history of race relations.

“Only United Methodists with a deep education in the church’s history know its full racist background.”

However, not all the resistance to Dismantling Racism has been from ignorance of the UMC’s history. Similar themes have been prevalent among United Methodists who’ve expressed outrage at the anti-racism initiative. Some see Black Lives Matter as a political movement in which the church should have no part. Some “blame the victim,” contending that those Black people who’ve died because of police brutality wouldn’t have been in trouble if they had obeyed the law. A small-but-vocal contingent clings to the idea of white supremacy, arguing that the Bible supports the superiority of the white race.

Because the United Methodist Church is organized as a “connectional” body (a topic we’ll unpack in a future essay), implementation of Dismantling Racism will be a decentralized effort based on four guidelines: pray, connect, show up, act.

A page of the official United Methodist website lists multiple resources for regional units known as annual conferences and local congregations to participate in the anti-racism initiative. Each annual conference, local congregation and individual United Methodist is free to participate as much as desired — or not at all. This makes the effectiveness of the initiative difficult to gauge statistically, because there’s no way to count how many hearts and minds will be changed to reject racial discrimination and embrace racial justice.

Sam McGlothlin, associate pastor of Belle Meade United Methodist Church, elbow bumps Officer Edward Rucker following “A Prayer Service To Stand Against Racism” held June 5 at Belle Meade United Methodist Church in Nashville, Tenn. (Photo by Kathleen Barry, UM News)

Nonetheless, Dismantling Racism has one thing going for it: the campaign has been embraced by multiple levels of the worldwide church, from the Council of Bishops that began it through men’s and women’s ministries to all program and administrative agencies. Not since the foundation of Africa University in Zimbabwe has there been such church-wide unity of mission.

The denomination’s men’s and women’s ministries offer prime examples. United Methodist Women, which has been at the forefront of anti-racism efforts throughout its 150-year history, has become a source of ready-made study resources. United Methodist Men, which has been dwindling because of the overall decline in male participation in church, has rebounded over the past two months to produce anti-racism resources and a booklet of prayers, and to hold virtual prayer services sponsored by four of the five U.S. jurisdictions.

Ultimately, independent grassroots action outside the official Dismantling Racism initiative may ensure, if not achievement of its goal, then certainly improvement. Local church members and clergy have posted videos and photos on social media documenting their participation in demonstrations across the United States since George Floyd died. Anti-racism committees (United Methodists love committees) have been formed or strengthened locally and regionally. Bloggers are filling screens with thousands of words on the scriptural basis for doing away with systemic and institutional racism.

Still, the idea that one group of people is inferior to another because of skin color remains endemic in humans. The reality that all of American society rests upon a foundation of white privilege proves such a revelation to most white people that they can’t grasp it mentally or emotionally.

However, the convergence of recent crises appears to be dropping the scales from lots of eyes.

“Bloggers are filling screens with thousands of words on the scriptural basis for doing away with systemic and institutional racism.”

Recently, a hospital chaplain, Caesar Rentie, participating in a church’s online panel discussion of racism, said he believes the coronavirus pandemic has made everyone “a little bit Black.” He elaborated that the invisible menace of COVID-19 and the public health restrictions designed to slow its spread have given white people a semblance of what it’s like for people of color to face daily indignities, confrontations and threats to their existence. Ironically, the emotional, psychological and spiritual impact of the coronavirus pandemic may have made it easier for white people to see the horror of George Floyd’s death, he said.

Certainly the United Methodist Council of Bishops saw Floyd’s death for what it was and remembered Methodism’s racist history. They responded with a call to lament the racial discrimination that has occurred in the church and American society, and to advocate that people of faith refuse to accept it anymore.

Whether the Dismantling Racism initiative achieves its ultimate goal — which as the late John Lewis said is the work of a lifetime — it appears to be helping United Methodists repent of their church’s racist past and resolve to do better in the future.

Cynthia B. Astle is a veteran journalist who has covered the worldwide United Methodist Church at all levels for more than 30 years. She serves as editor of United Methodist Insight, an online journal she founded in 2011.

Related articles:

Is the United Methodist separation still on?