There’s something happening here, what it is ain’t exactly clear.

Two days after Joe Biden was declared winner of the 2020 presidential election, Paula White, the ex-president’s thrice-married spiritual advisor, launched into a stunning rant. “I hear victory in the corridors of heaven,” White told her congregation, in a staccato, machine-gun cadence. “Angels have even been dispatched from Africa right now. They’re coming here, in the name of Jesus, from South America.” The angelic mission, apparently, was to “stop the steal.”

Two months later, Ché Ahn, a close ally of White, issued a stunning prophecy at the Joshua March in Washington, D.C., that had reporters Googling biblical references. “This is the most important week in America’s history,” Ahn declared two days before the Jan. 6 insurrection. “I believe that this week we are going to throw Jezebel out, and Jehu is going to rise up, and we are going to rule and reign through President Trump, and under the worship of Jesus Christ.”

Televangelist and personal pastor to Donald Trump, Paula White Cain, speaks during a Trump campaign event courting devout conservatives by combining praise, prayer and patriotism, Thursday, July 23, 2020, in Alpharetta, Ga. (AP Photo/John Amis)

Three months later, Rick Joyner, head of Morning Star Ministries in Charlotte, N.C., told Jim Bakker about a revelatory dream from 2018. Joyner urged “true disciples of Christ” to get their weapons ready because, according to Jesus, we are heading for a second American Revolution (or Civil War) in which God-ordained “militias would pop up like mushrooms.” The good news, he said, was that victory was assured.

The New Apostolic Reformation

White, Ahn and Joyner are associated with what has been called the New Apostolic Reformation, a loose network of preachers, prophets, churches and parachurch organizations that typically goes by the acronym NAR (pronounced “nahr”). But NAR is neither a denomination nor a formal organization; it’s a loosely connected movement of likeminded individuals, churches and ministries.

The central NAR tenet is that churches should be run by apostles and prophets. The prooftext is the “five-fold ministry” referenced in Ephesians 4:11 (apostles, prophets, evangelists, pastors and teachers).

NAR ministries are run by apostles endowed with the full authority Jesus granted to the “the twelve.” When Paula White threw in her lot with the Apostolic Movement, she laid down the law to her people. “God is a theocracy, not a democracy,” she said. So, people could “get in, get out or get run over.”

Rick Joyner

In the NAR world, God speaks through modern-day prophets like Rick Joyner and Heidi Baker just as God inspired the words of Jeremiah and Isaiah. Prophets inform the work of apostles but must work under apostolic authority.

Dominionism

The apostolic-prophetic movement is closely associated with “dominionism,” the idea that God wants the church to build “the seven mountains of culture” (education, government, media, arts, entertainment, religion, family). In so doing, the church will usher in the universal kingdom of God. Seven-mountains dominionism is a scaled-down version of Rousas Rushdoony’s “theonomy.” According to Frederick Clarkson, C. Peter Wagner repeated a simple mantra about dominionism, “We have an assignment from God to take dominion and transform society.”

Dominionist theology is not universally accepted on the far right, but it has become the leading view. Either the church will be reduced to just-another-religion status, the thinking goes, or her dominant status must be enforced and extended. During the 1980s, a silent war emerged between dispensationalism and New Apostolic thinking. Rooted in the idea that civilization must inevitably erode prior to the rapture, dispensationalists were disinclined to engage politically. What was the point? But if the dominionists were right, it was possible to fight and win a culture war.

Fleeing from a label

When Terry Gross interviewed Wagner on Fresh Air in 2011, he flatly denied that he was advocating theocracy. But, as Clarkson makes clear, Wagner had an entirely different message for his own people. “Dominion has to do with control. Dominion has to do with rulership,” Wagner told a NAR conference in 2008. “Dominion has to do with authority and subduing … . Dominion means being the head and not the tail. Dominion means ruling as kings.”

“Dominion means being the head and not the tail. Dominion means ruling as kings.”

Strategic and pragmatic, NAR leaders work through loose networks on the Christian right and are willing to cooperate with those who don’t share their entire theology. They focus on the Pentecostal and charismatic branches of American Christianity, but NAR influence extends well beyond that world. Apostles and prophets invite one another to speak at movement events, they endorse one another’s books and swap appearances on podcasts and television programs. Some NAR apostles subscribe to the prosperity gospel; others do not. There is a lot of NAR-lite on offer in the American religious marketplace. The influence can be subtle. Most contemporary Christian music today comes out of two churches: Australian based Hillsong and Redding, Calif.-based Bethel, multi-campus congregations that take their NAR teaching full-strength.

Mike Bickle

Prominent figures within the apostolic movement like Mike Bickle of the International House of Prayer in Kansas City or Bill Johnson with Bethel Church in Redding, Calif., claim NAR is a pejorative category invented by their critics. This is a straw man argument. No one claims the NAR is a denomination or a formalized group; but it is a movement defined by an identifiable constellation of beliefs.

The Latter Rain Movement

The restoration of the apostolic and prophetic offices can be traced back to the Latter Rain Movement of the 1940s. While preaching in Vancouver in 1947, William Branham’s preaching about the “Manifest Sons of God” (apostles and prophets) profoundly impacted a group of visitors associated with the Sharon Orphanage Schools of North Battleford, Saskatchewan. They invited Branham to visit their school, and it was there the movement took root.

Peter Wagner

The Latter Rain Movement grew rapidly but was forced underground after being denounced as heretical by the Pentecostal establishment in North America. But with the charismatic renewal of the 1970s, Latter Rain ripples began washing up on the coast of California.

C. Peter Wagner

This was largely thanks to C. Peter Wagner, a nerdy professor of missions and church growth at Pasadena’s Fuller Theological Seminary. Wagner’s experience as a missionary in Bolivia had convinced him that conventional evangelistic techniques focused on saving souls one-by-one. In Wagner’s experience, the mass conversion of entire family units and entire social networks should be the norm.

Readers who attended seminary in the 1970s will recognize this as an outgrowth of the “homogeneous unit principle,” the idea that people are more likely to cross religious and cultural barriers when accompanied by members of their social, ethnic and economic tribes.

Kingdom Now theology

The kind of mass conversion Wagner envisioned would require a dramatic precipitating event — in other words, a miracle. Wagner’s interest in spectacular manifestations of the Spirit led him to John Wimber, a young neo-Pentecostal pastor who was experimenting with what he called “power evangelism.”

John Wimber

Wimber saw religious conversion as a kind of spiritual contest. The power of the Holy Spirit was set against whatever power the demonic force controlled in an individual or community. People came to Christ when “the Jesus stuff” (miracles of healing and exorcism) revealed transcendent power.

His budding friendship with Wagner brought Wimber onto the campus of Fuller Seminary, where he encountered the “inaugurated” eschatology of evangelical biblical scholar George Eldon Ladd. Ladd’s thinking borrowed heavily from Oscar Cullmann, a continental scholar who stressed the “already-and-not-yet” character of the kingdom of God.

Oscar Cullman

Writing in the wake of the Second World War, Cullman suggested that Christ’s victory on the Cross was comparable to the Allied Landing on D-Day. There was still plenty of fighting to be done, but victory was assured. Cullmann compared the Second Coming of Christ to VE Day, the actual cessation of armed conflict.

Cullmann was no fundamentalist but, unlike Rudolph Bultmann, he used the “spiritual warfare” language of the New Testament without embarrassment or apology. After the horrors of fascism and the Holocaust, the demonic no longer felt like a vestige of medieval superstition.

Although Ladd held a doctorate from Harvard, he never outgrew the biblical literalism of his evangelical tribe. The only demons he had encountered personally were alcoholism, depression and dementia (that’s another story), but he never doubted the existence of angelic and demonic beings. They were in the Bible.

Ladd was the sworn enemy of dispensationalism. There was no biblical warrant, he said, for believing the church would be raptured to heaven prior to the great tribulation. Instead, God would use the patient endurance of the church to prepare for the Second Coming of Jesus on the clouds of heaven. Ladd was a bit vague on the details, but his disciples quickly filled in the details in spectacular fashion.

George Eldon Ladd

Ladd’s evangelical version of inaugurated eschatology answered questions that had been nagging at John Wimber. The converted entertainer (he once played keyboards for the Righteous Brothers) thought in the simple categories of a layman. If Jesus healed the sick and cast out demons, Wimber reasoned, the church should too. The Bible said as much. Yet when he first started praying for the sick, it took nine months to get his first miracle. After years of trial and error, Wimber had learned the tricks of the spiritual warfare trade, but even on a good night, not everyone was healed. Why not?

Ladd’s already-and-not-yet theology provided the answer. God had broken off a chunk of the consummated kingdom of God and inserted it into the present moment. That was the “already” part. The “not yet” piece of the equation accounted for the hit-and-miss character of Wimber’s power evangelism.

The motto of the mid-century Latter Rain movement had been “kingdom now.” That isn’t what inaugurated eschatology was saying, but that’s what the apostolic movement heard. If God wants to take dominion prior to the Second Coming, new problems arise. What do we do with the people who refuse to bend the knee to the apostles and prophets of the church? How do we get from where we are (a world of infinite religious, political and cultural complexity) to a world in which “every knee shall bow and every tongue confess” without the most draconian kinds of coercion? Ultimately, NAR ideology is inconsistent with democracy, in the church or anywhere else.

Embracing the supernatural

To the chagrin of Fuller’s theology, ethics and New Testament faculty, Wimber and Wagner developed a wildly popular “Signs and Wonders” seminary course. Wagner provided the theological background, and the laid-back Wimber would do the Jesus stuff.

Wagner became convinced that modernism, with its rationalistic and skeptical spirit, was the bitter enemy of “the biblical worldview.”

“Who needs healing today?” Wimber would ask. Hands would go up. This pragmatic approach would become an abiding feature of the NAR movement: If people can be taught to speak in tongues, they can be taught to heal the sick and cast out demons.

Influenced by the thinking of Francis Schaeffer, Wagner became convinced that modernism, with its rationalistic and skeptical spirit, was the bitter enemy of “the biblical worldview.” Instead of moving forward into postmodern analysis, Wagner retreated to a pre-modern (he would say “biblical”) posture.

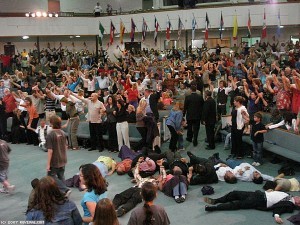

Worshipers receive the “Toronto Blessing” as they lie prostrate on the floor.

It wasn’t long before extraordinary manifestations of the Spirit were breaking out everywhere. A handful of preachers known as the “Kansas City Prophets” were doing amazing things in Missouri. In Toronto, a modest charismatic church was growing like wildfire. Overflow services were being held six nights a week. People laughed hysterically, rolled on the floor, or raced about the room, their hands flung high in ecstasy. Before long, hundreds of thousands were flying in from all over the world to experience “The Toronto Blessing.”

Many of the contemporary leaders of the apostolic movement trace their success to a transformational worship experience. Heidi and Rolland Baker struggled on the African mission field for two decades with little to show for it. Then they plugged in to the Toronto Blessing and came away energized and empowered. Miracles abounded. Hundreds of churches sprang up in response to their teaching.

Knowing that you know that you know

Paul Tillich’s maxim has become axiomatic throughout progressive Christianity: “The opposite of faith is not doubt, but certainty.” Pete Enns, for instance, wrote a book called The Sin of Certainty. The Apostolic Movement has grasped the opposite end of the stick. In this world, certainty is essential.

On a recent episode of the NAR-related podcast Miracles and Atheists, Nicole Welch, an apostolic missionary to Honduras, summed up the new orthodoxy. “We need to know that we know that we know,” she said. “That’s belief!”

Photo from International House of Prayer Facebook page, 2021.

NAR-influenced books, magazines, television shows and podcasts are awash in miracle stories and, according to NAR Apostle Rick Joyner, we ain’t seen nothing yet. In the not-too-distant future, Joyner has prophesied, “news teams will follow apostles like national leaders, recording great miracles.” These miracles will “exceed even some of the most spectacular biblical marvels” and “will cause whole nations to acknowledge Jesus.” In fact, “the appearances of angels will be so common that they will cease to be related as significant events.”

Mapping the spiritual realm

Peter Wagner coined the term “New Apostolic Reformation” in 1994. It was his way of hanging a name on an emerging phenomenon. The descriptor didn’t always take, but the package of power evangelism, apostolic polity and dominionism proved to be highly marketable. NAR doctrine has been particularly effective in Africa, South America and parts of Asia, places where enlightenment rationalism never gained a foothold. Paula White’s “angels from Africa” rant reflects this reality. Trump is very popular among African evangelicals, especially in Nigeria, Kenya and Angola.

White’s eyebrow-raising rhetoric flows from the concept of “spiritual mapping,” the idea that each geographic location is controlled by a unique super-demon which must be addressed on his or her own terms. Wagner embraced this notion with enthusiasm, teaching that the regions located just to the north and south of the equator are controlled by a powerful demon he called the “Queen of Heaven.” Until Christians engaged in spiritual warfare with the Queen of Heaven, Wagner taught, the results of evangelism in the affected regions would be disappointing.

White’s eyebrow-raising rhetoric flows from the concept of “spiritual mapping,” the idea that each geographic location is controlled by a unique super-demon which must be addressed on his or her own terms.

A recent article in the Washington Post featured a NAR-affiliated Fort Worth congregation that divided the city into four quadrants, each dominated by a different demon. “Greed, the map read over the west side. Competition, it said over the east side. Rebellion, it said over the north part of the city. Lust, it said over the south.” The congregation also engages in frequent prayer walks through parts of Fort Worth, another feature of spiritual mapping.

Wimber’s worries

Fuller’s Signs and Wonders course came to an unceremonious end when Wimber and Wagner developed irreconcilable differences. For Wimber, spiritual mapping was a bridge too far. Their cooperative relationship took another hit when the Kansas City Prophets, men like Mike Bickle and Paul Cain, moved in an authoritarian direction. Wimber was concerned; Wagner wasn’t.

This pattern was repeated when “the Toronto blessing” worship services moved from “holy laughter” to animal noises. Wimber advised the pastors to re-evaluate; Wagner didn’t see a problem.

Wimber’s growing caution was partly a function of rapidly declining health. In 1993, he was diagnosed with an inoperable cancer. “I began to cling to every nuance of the doctors’ words, shrugs and grimaces,” he admitted to his followers. “I experienced the full range of emotions that go with a life-threatening illness. I wept as I saw my utter need to depend on God. The fear of the unknown often gripped me.”

In 1997, weakened and struggling with the early stages of dementia, Wimber died after a serious fall led to a fatal brain hemorrhage. He was only 59 years old.

Driving without brakes

I suspect the man who brought “signs and wonders” into the evangelical lexicon would be dismayed by what has become of his movement. The “kingdom now” doctrine popular in NAR circles places so much emphasis on the “already” side of the eschatological equation that the harsh reality of “not yet” is often forgotten.

Having effectively jettisoned reason and the voice of tradition, latter-day prophets and apostles are driving without brakes.

The new apostolic reformation is the most recent iteration of the holiness movement John Wesley unleashed in the 18th century. But Wesley taught that Christians could appeal to four sources of authority: Scripture, experience, tradition and reason. Having effectively jettisoned reason and the voice of tradition, latter-day prophets and apostles are driving without brakes.

The temptation to divinize personal prejudice is overwhelming and largely unrecognized. The movement’s embrace of MAGA politics should give us pause. Does NAR speak for Almighty God, or is it just a particularly elaborate species of white Christian nationalism?

Can you top this?

Ché Ahn

Before Wagner died in 2016, he passed his apostolic mantle to Ché Ahn. Although the Vineyard Movement launched by Wimber continues to thrive, no one has stepped forward to champion his brand of irenic and good-natured supernaturalism. In recent years, the apostles and prophets associated with NAR have been locked in an informal competition to make the most striking statement or to describe the most mind-boggling miracle. A can-you-top-this mentality has emerged. As a consequence, the kind of bizarre rhetoric that introduced this piece has become all too common.

The unchecked supernaturalism of the movement has produced a Manichean form of angel-demon dualism. Mike Bickle, with the lnternational House of Prayer in Kansas City, teaches that, during the “tribulation,” God’s true church will pray the plagues of Revelation down upon a demon-infested and unbelieving world. A strong undercurrent of resentment and a thirst for revenge courses through NAR proclamation.

Radical dualism

If our side is validated by miracles and direct communication with the Almighty, NAR teaching suggests, we must be on the side of the angels. Churches that reject our teaching are rejecting God and dabbling with the demonic. Atheists, liberal Christians, Hindus, Muslims and Buddhists are demonized in the most crude and literal fashion. Bigotry toward the LGBTQ community knows no bounds.

NAR-generated conspiracy theory merges easily with Christian nationalism, the militia movement and QAnon. It would be a gross oversimplification to blame the Jan. 6 insurrection on NAR, but their hyper-partisan brand of Manichean dominionism clearly contributed to the insurrectionist mindset.

If the other side is literally demon-possessed, how can you compromise?

Dominionist dualism has little patience for the pragmatic give-and-take of secular politics. If the other side is literally demon-possessed, how can you compromise? The only option is absolute victory. NAR-style paranoia has exercised a leavening influence in contemporary Republican politics at the state and national level and is particularly prevalent in Texas.

NAR apostles and prophets have little interest in comparing notes with their ideological opposites. The challenges mounted by feminists, the Black Lives Matter Movement, and gay rights advocates are either ignored or rejected out of hand. This can create problems.

Paula White’s joined-at-the-hip relationship with the ex-president shocked her large Black constituency. T.D. Jakes, White’s erstwhile mentor, has been forced to distance himself from her ministry. The sudden emergence of Donald Trump has exacerbated the tension between white and Black evangelicals across the nation.

NAR-related churches clearly appeal to a significant segment of American young adults, but, in general, the younger cohorts of the American population are moving in an entirely different direction. Rick Joyner’s call to a religious civil war may resonate with portions of the Republican base, but his own children are unimpressed. “He talks about Democrats being evil, forgetting that all five of his kids vote Democratic,” one of his daughters told the New York Times. “Who is he asking his followers to take up arms against?” she asked. “Liberal activists? That’s me.”

Demographic studies suggest that, for every young person who walks through the door of a NAR-oriented congregation, two or three are walking away from organized religion. For millions of American young people, NAR-style dominionism has become the face of American Christianity, and they are appalled by what they see.

Providing an alternative to NAR religion

Religious moderates and progressives lack a shared vision. We aren’t sure what to make of the Bible, so most of us choose to ignore it, or to focus on the bits about love, justice and mercy. We have no idea what to make of angels and demons. A 2008 Pew study concluded that “68% of Americans believe that angels and demons are active in the world.” Moreover, young people are just as likely as their parents and grandparents to hold supernatural beliefs.

These studies suggest that there is a large and motivated audience for the kind of miracle stories and angel-demon dualism we find in the NAR religious vision. The market for a form of Christianity that minimizes the importance of biblical authority and the supernatural is vanishingly small and may be shrinking. Hollywood is just as enamored of miracles and the paranormal as C. Peter Wagner and Paula White. The difference between a Marvel superhero and a guardian angel is slight.

As a consequence, NAR-style religion controls a huge share of the religious market. I am reminded of Yeats’ famous line, “The best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity.”

If progressive Christians hope to counter the NAR religious package, we must come to terms with the angel-demon language of the New Testament and the healing ministry of Jesus.

If progressive Christians hope to counter the NAR religious package, we must come to terms with the angel-demon language of the New Testament and the healing ministry of Jesus. We must enter into intense conversation with biblical scholars, theologians, sociologists of religion and Christian ethicists who have light to shed on these issues.

We will want to reinterpret these symbols, perhaps along the lines Walter Wink has suggested, but we dare not ignore them. Using the simple categories of everyday conversation, we must be able to explain how we believe God speaks to us through the Bible, how we understand “the gospel,” what it means to call Jesus the Savior of the World. Finally, we must explain how we can hold these commitments without silencing or discounting other religious and non-religious perspectives.

If we continue to “lack all conviction” while conspiracy theorists are “full of passionate intensity,” the madness of Jan. 6 could become a normal feature of our national life.

Alan Bean

Alan Bean serves as executive director of Friends of Justice, an alliance of community members that advocates for criminal justice reform. He lives in Arlington, Texas.

Related articles:

Trump treats evangelical supporters to ‘state dinner’

SBC president leads prayer at meeting of ‘dominionists’

Christian nationalism and the looming death of religious liberty | Opinion by Jonathan Davis