First there was Jason Aldean topping the Billboard Hot 100 with “Try That in a Small Town.” Then, two weeks ago, Oliver Anthony’s “Rich Men North of Richmond” became the first song ever to top the Billboard Top 100 by a singer who’d never hit the list before.

What’s going on here? Is the Revolution right around the corner? Are the dispossessed and left behind finally gonna get what they’re due: recognition, respect, revenge?

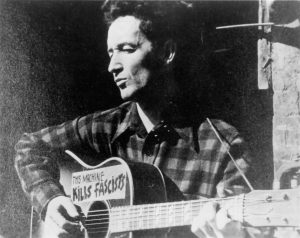

Well, I don’t know; but those are protest songs, and they stand in a proud American tradition. Nearly 85 years ago, 1940, at the tail end of the Great Depression, Woody Guthrie sang “Blowin’ Down This Road.” The angry refrain, “An’ I ain’t a-gonna be treated this way” rings out nine times throughout the song.

And how was he treated? — “I’m a dust bowl refugee” who’s “a-lookin’ for a job at honest pay,” whose children “need three square meals a day” and whose two-dollar shoes hurt his feet.

Photo of Woody Guthrie, circa 1940. (Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

Today, nearly 85 years later, Oliver Anthony sounds a whole lot like Woody. He’s “workin’ all day/overtime for bullshit pay,” while “we got folks in the street, ain’t got nothin’ to eat” and “young men are puttin’ themselves six feet in the ground/ ’cause all this damn country does is keep on kickin’ them down.”

Unlike Anthony, Jason Aldean is speaking for himself and like-minded “good ol’ boys raised up right.” They’ve “got a gun my granddad gave me” and they’ll “see how far ya make it down the road.”

How far ya make it, that is, after “carjack(in’) an old lady at a red light,” “cuss(in’) out a cop” or “stomp(in’) on the flag.”

Twenty plus years after Guthrie declared, “I ain’t a-gonna be treated this way,” in 1962, Bob Dylan was equally despondent about the state of his world. The second verse of his “Song to Woody” goes like this:

Hey, hey, Woody Guthrie, I wrote you a song ‘bout a funny ol’ world that’s a-comin’ along; Seems sick an’ it’s hungry, it’s tired an’ it’s torn. It looks like it’s a-dyin’ an’ it’s hardly been born.

That was a year before the Kennedy assassination and six years before the King assassination. What was the world coming to, you might ask.

Marvin Gaye picked up the mantel of protest with “What’s Goin’ On” in 1971 — “Mother, mother/there’s too many of you crying/brother, brother, brother/there’s far too many of you dying.” In 1970, protesting students were shot and killed by National Guard and police at Kent State in Ohio and Jackson State in Mississippi.

There’s not room here for the next 50 years of American protest songs, but the point is clear: There’s a bright through-line in those protest songs since 1940: unfairness — a belief that I am being treated unfairly and I’m not the only one. What has caused this widespread belief is way beyond my paygrade, but I do know, as you probably do, some of the ground from which it springs.

“Today we are in danger of falling back into those oppressive, pre-democratic days.”

The seeds of this democratic experiment called the United States of America were planted in the soil of the Democratic Revolutions that began in 17th century Europe with calls for government by consent of the governed, not government ordained by God. Yet today we are in danger of falling back into those oppressive, pre-democratic days.

I’m indebted to historian of Christianity Marcus Borg for the following prescient insights. In a 2014 lecture on the social world of the Ancient Near East, Borg cited four distinctive characteristics. Those times were (1) politically oppressive (elites ruled by decree); (2) economically exploitative (elites imposed heavy taxes and owned most of the land); (3) chronically violent (Rome’s legions controlled unruly peasants, and wars to control more land were common); and (4) the social order (see 1-3 above) was legitimated by religion (monarchs ruled by divine right).

This hits much too close to home. Look around. An awful lot of perceived unfairness in America today comes from (1) the feeling of being shut out of the political system; (2) the feeling of being exploited economically; (3) the violence that haunts us daily; and (4) sectarian religion being inserted into politics by the evangelical Christian right (political debate is impossible when their God is your alleged opponent). Thus we are in danger of recreating the culture of the Ancient Near East, today, right here in the United States, the world’s oldest democracy.

So we need protest songs. More than ever. Bring ’em on!

“We Shall Overcome” was and is about much more than being free to eat at a lunch counter or register to vote. In the 1960s, it was about resisting a political, economic and religious system of domination. Today, we are in danger of recreating that very system.

And resist, we must. Our future depends on it.

Richard Conville is a retired professor of communication studies and longtime resident of Hattiesburg, Miss. This column originally was published in the Pine Belt News.

Related articles:

‘Freedom songs’ make a reprise during this year of protests

Music and change, blowin’ in the wind | Opinion by Phawnda Moore

Learning from the political worship songs of our American past | Analysis by Rick Pidcock