It’s hard to believe it’s been 60 years since President John F. Kennedy was assassinated on the streets of downtown Dallas. For many who were alive at the time, it has become a distant memory of a national tragedy. And for many of the millions in the U.S. population who hadn’t been born yet, it may be nothing more than a few paragraphs in the history books.

However, a collection of sermons delivered by Dallas clerics in the dark days following what happened in their city Nov. 22, 1963, sheds some light on the perspectives and moods of church leaders and their congregants.

The sermons, held in the archives at Southern Methodist University, include three given on Nov. 24, just two days after the assassination:

- “Day of Distress,” by Charles V. Denman, pastor of Wesley Methodist Church

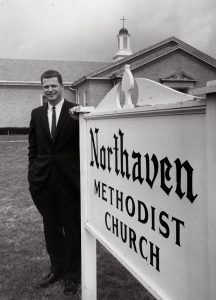

- “One Thing Worse Than This,” by William A. Holmes, pastor of Northaven Methodist Church

- An untitled sermon by Bill Dickinson, pastor of Highland Park Methodist Church

In addition, the collection includes two messages given in the weeks and months that followed:

- “The Fifth Freedom: Freedom from Hate,” given Nov. 28, Thanksgiving Day, by Jimmy Allen, secretary of the Christian Life Commission, Baptist General Convention of Texas, at a community Thanksgiving service in the Oak Cliff area of Dallas

- “What Should Dallas Do?,” a message given by Rabbi Levi Olan of Temple Emanu-El, Jan. 19, 1964, over the airwaves of KRLD-AM radio

Cultural relevance

Matthew Wilson, political science professor at SMU and director of the Center for Faith and Learning, said one of the most compelling aspects of the sermons is their relevance to life in the United States today.

Matthew Wilson

“The cautions against extremism, the cautions against hatred and contempt for one’s political rivals — those are every bit as relevant in 2023 as they were in 1963,” he said. “And it shows that the good old days that we often think about in our politics weren’t maybe as good as we remember them in the sense that this level of acrimony goes back a long way. What we see today has roots that are pretty deep. It’s not just a phenomenon of the last 10 years or so.”

An example can be found in the words of Allen:

A climate of character assassination, carping criticisms toward national leaders and constant complaint about the processes of law has developed in our nation. Dallas is not the only city where this has been present. But it has been present here!! Disrespect for persons and for democratic processes has grown to alarming proportions in our community and encourages the venting of hatred both by young and old. In some quarters it is not only permitted but considered righteous to attack the Supreme Court on every opportunity. Politicians are branded as corrupt to such a degree that many good men refuse to enter political activity because of public attitude.

And Dickinson said:

There are among us today too many purveyors of hate, people who call intelligent sincere holders of public office, traitors; people who fill our cars with leaflets bearing printed lies and calling our public officials, disloyal; people who fill our mail with emotional, bitter harangues and accusations and who make harassing telephone calls to our honest and sincere citizens at all hours of the night. And then there are those who give subtle approval to such extremists and breeders of hate through either indifference or through financial support.

“There are those who give subtle approval to such extremists and breeders of hate through either indifference or through financial support.”

Denman pointed a finger at the church and his own denomination:

Our nation is sick unto death and nothing but repentance will save it, and the church cannot stand aloof from the sickness of the nation. The church is sick unto death too. Sometimes I think the church is like a diseased tonsil, put in the body to trap infection it has become a source of infection.

Much of the hate and discord that has been poisoning our nation has been preached in the name of Christ and the church. In Dallas entire sermons have been devoted to damning the Kennedy administration and the United Nations, and they have been delivered from Methodist pulpits. In the name of the church men and women have sown seeds of discord, distrust and hate and have called it witnessing for Christ. As a church we are sick. God have mercy on us.

Collective guilt: Was Dallas to blame?

While those words calling out purveyors of discontent may sound familiar, Wilson said the pastors’ comments on “collective guilt” may seem foreign to readers and listeners today.

“The sense that somehow Dallas could be held collectively responsible for the Kennedy assassination, I think, strikes the contemporary ear as unusual, but it was widely talked about apparently at the time; the idea that somehow Dallas corporately bore some level of blame for Kennedy’s assassination,” he said. “I mean, you can imagine, God forbid, Joe Biden were to be assassinated out on a campaign stop in Tampa or Minneapolis or Pittsburgh. Nobody would say Tampa bears the guilt for this. It would be focused on whoever was the assassin. But there really was a sense that Dallas collectively had to grapple with this.”

Indeed, Dallas already had set itself up for scrutiny prior to the assassination with two incidents that made national headlines. Three years earlier, Vice President Lyndon Johnson and his wife were spat on and cursed by a crowd in the lobby of a Dallas hotel. And a month before the assassination, Adlai Stevenson, U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, was heckled and interrupted during a speech, and was hit in the head with a sign and spat on as he left the auditorium. Those incidents, as well as the leanings of local editorial writers, painted Dallas as a hotbed of right-wing extremism.

“Of course, what messed up the narrative was that it turned out that Lee Harvey Oswald was not some sort of far-right John Bircher. He was a far-left guy,” Wilson said. “He was a communist sympathizer who spent time in Moscow. So that kind of upset the whole apple cart in terms of the ideological story. But then as at least one of the pastors emphasized in his sermon, extremism does not know ideological boundaries.”

“Hate knows no political loyalty and is as deadly and as vicious in the heart and mind of those to the far right as those to the far left alike.”

Wilson is referring to Highland Park Methodist’s Dickinson, who said:

Isn’t it ironic that the suspect for the attack on President Kennedy and Gov. Connally is a pro-communist, an extreme leftist, when only recently our city made the headlines with the activities of the extremists from the far right at the time of Stevenson’s visit? But if the fact is ironic, it is also prophetic. Hate knows no political loyalty and is as deadly and as vicious in the heart and mind of those to the far right as those to the far left alike.

Allen tackled the topic of Dallas’ culpability with these words:

Those of us who are concerned about the “image of Dallas” are correct in stating that it could have happened anywhere … in any city. The stigma of the deed itself cannot be laid at the feet of our city as if the collective will of our people would have wished it.

However, something far deeper and more disconcerting is the fact that so many in our nation were not surprised that it happened here! What has grown up in a city of great pride, achievement, orderliness and stability which would cause a Billy Graham or an Adlai Stevenson to attempt seriously to dissuade any president of the United States from visiting for fear of violence to him?

JImmy Allen

The most chilling sound of those dreadful four days to me was not the crack of a gun, nor even the weeping of mourners. It was the cheer which came from the crowd across from City Hall when word came that Oswald had been murdered in the basement of the police station! Here is hatred laid bare in all of its ugliness!

That hatred may be more sophisticated in selecting socially approved objects for its venom, but it is the same stuff which triggered a sniper’s bullet or threw a bomb into a Negro Sunday school in Birmingham.

To those who protest that these are not really representative of Dallas, the obvious answer is that they are representative of an element of our city. The white heat of a hate-filled atmosphere allowed the necessary warmth for this element to crawl out from under the rocks to be seen.

Olan noted the apprehension in the community before the president arrived:

Behind our apprehension lay the fact that we had become the No. 1 spot in the nation for intolerance. We had been put to shame several times by rudeness, crude manners and even violence. It is not uncommon for the president of the United States to visit communities hostile politically to him. But we were afraid of an “incident,” the word which was first used in the announcement of the assassination to the audience waiting eagerly for the president to arrive. The fact is that we are like all other cities, with this difference, however we were troubled lest something should happen.

Holmes was wary too:

Dallas has been my home now for the last 12 years. I hope it will be my home for many years to come. It is a city that I love and hold in high regard. We have many graces and human decencies of which I am extremely proud. But we cannot month after month, year after year, sow the seeds of intolerance and hate and then upon learning of the president’s visit just throw a switch and hope all rancor will disappear. The vocal, organized and unorganized extremists have captured us — while we were sleeping in the night. And there is no way in all creation to avoid our corporate and mutual guilt.

“By our timidity, we have encouraged the aggressor; by our paralysis we have given safe conduct to reactionaries.”

By our timidity, we have encouraged the aggressor; by our paralysis we have given safe conduct to reactionaries; by our confusion we have promoted the clarity of evil; by our small prejudices and little hates we have prepared the way for monstrous and demonic acts that have betrayed us all. We have become a garbled people, mistaking patriotic cries for patriotism, boisterous boasts for courage, and superficial piety for faith. In this week of blood-stained history and death, we are under an imperative to whisper unto one another and to God: ‘O Lord, have mercy on us all.’”

Scripture and sermon pivots

Pastors today might marvel at how these preachers stood in their pulpits and delivered their messages just two days after such a tragedy. Some admitted to struggling with the material, but all apparently were able to shape a message based on Scripture:

Denman pivoted with a message from the Old Testament:

This service was to have been a Thanksgiving service but because of the tragic event of Friday it has become a service of mourning. A Thanksgiving sermon had been announced and a Thanksgiving text chosen. Instead of the text previously chosen I am taking as my text this morning words spoken a long time ago in a time of great national peril. The text is, “This day is a day of distress, of rebuke, and of disgrace; children have come to the birth, and there is no strength to bring them forth,” II Kings 19:3.

Dickinson turned to the Gospel of John:

In the Gospel of John, Jesus prayed for the church and said to the Father, ‘As thou didst send me into the world, so have I sent them into the world.’ And the Master was talking about us, you and me. This is the reason that somehow I cannot find within my heart this morning a willingness to place the blame for the tragedy of this hour solely upon the man who pulled the trigger, for as a Christian I have been sent into this world as a child of God, and I am thus responsible to live in keeping with his law, though this I have not always done. In as much as the world of business and politics, of social relationships and government, is the real world in which I live, here it is in which my faith must find expression.”

Holmes went to the Gospel of Matthew:

William Holmes

I have several alternatives before me now as I begin this sermon. I could eulogize John Kennedy. This would not be hard for me to do. Or I could deliver myself of all my pent-up bitterness toward Lee Harvey Oswald, his alleged assassin. This would not be hard for me to do. But after brooding prayerfully the last 48 hours about this sermon offered in the name of God, I am very clear this morning that our mission in this service is neither one of eulogy nor of catharsis.

My text is taken from the Gospel of St. Matthew, which tells the familiar story of Pontius Pilate delivering a carpenter from Nazareth into the hands of first century extremists, and then washing his own hands in a bowl of water and declaring boldly to the crowd: “I take no responsibility for the death of this man.”

Olan took his Dallas radio audience to dark days in the history of Jerusalem:

Jerusalem, in the year 520 B.C., was a city despised and scorned by the surrounding nations. She had been decimated by enemies, and those who had returned to her from exile were weak and fearful. As is so often the case in the Bible, it is at this point that a prophet appears to console the people and challenge them to new greatness. Zechariah, a prophet of visions, speaks to Jerusalem in her hour of dismay. “So the angel that spoke with me said unto me: ‘Proclaim thou saying: “Thus saith the Lord of Hosts: I am jealous for Jerusalem and for Zion with a great jealousy. She is not forsaken of God who loves her and will guard her.’’'”

Allen listed three Scriptures — Daniel 9:3-8, Colossians 3:12-17 and John 14:6 — at the top of his manuscript. Echoing the words from Daniel — “We have been wicked and have rebelled; we have turned away from your commands and laws” — Allen said:

Hate is not just the product of social processes or political opinions. It is the fruit of man’s warped and sinful nature. Nothing short of the grace of God moving with power into a life can provide the right antidote for it. Whose is the sin in this atmosphere of hate? Every preacher who studiously ignores hate in the hearts of his people while he talks eloquently of the dimensions of the temple in ancient Jerusalem. Every citizen who tolerates the Jack Rubys of our community contributing to our moral decay because the tourist trade they draw increases profits. Every editorial writer who slashes away at respect for leadership by appealing to the prejudices of his reader instead of to the court of reason in a fair presentation of his political point of view, and every Christian who rejects his responsibility to think and act for Christ with a shrug of the shoulder and a muttered “What’s the use?”

The first Catholic president

SMU’s Wilson said it is unfortunate there is not a Catholic homily in the collection, given the president’s historic turn as the nation’s first Catholic president and the concerns that generated in some corners that he would be “taking his orders” from the pope.

“When John Kennedy ran for president in 1960, his religion, his faith was a significant issue or something he had to overcome, something he had to speak about to establish that you could be Catholic and be authentically American, be elected to the highest office in the land,” Wilson said. “He accomplished that, and in the three short years between his election and his assassination, it is remarkable how much those sectarian divisions did diminish, where in the wake of his assassination, he was not identified as the Catholic president, he was the president. And I think you see that tone reflected in some of these sermons as well.”

Charles V. Denman

Among the Dallas pastors, Denman addressed Kennedy’s faith directly:

Here was a man with the wisdom to know that nations do not perish because of power from without so much as they perish because of decay from within — because of their own selfishness and greed and complacency. He tried to stem the rising tide of selfishness and greed. He tried to put Christian ideals into international relationships. He was a Christian statesman of the highest order, and we accused him of being a cheap politician.

Greatness was passing by, and we didn’t have the wisdom to see it or the decency to appreciate it. The dreams of this man were too great for our shrunken hearts. We couldn’t hear what he was saying because we were listening to the selfishness and prejudices of our own hearts.

“Now he is neither Roman Catholic, Yankee or Democrat but an immortal: a man who had to die because his dreams were too big.”

Some of us couldn’t hear him because he was a Roman Catholic. Some of us couldn’t hear him because he was a Yankee. Others of us couldn’t hear him because he was a Democrat. Now he is neither Roman Catholic, Yankee or Democrat but an immortal: a man who had to die because his dreams were too big.

Personal stories of the day

Another interesting feature of the sermons is the personal stories two of the men shared. Highland Park’s Dickinson began his sermon telling how he was among those at the Dallas Trade Mart awaiting the arrival of the president when they got the news that Kennedy and Texas Gov. John Connally had been shot.

William Dickinson

At the very moment of apparent triumph, our world crumbled around us, and we became very conscious of our complete inadequacy to face the cold, hard facts with which we were involved. … What we were told was simply beyond our capacity to understand. It could not be true. Such things happened in story books and fiction, in other countries, but it was too unreal, too fantastic to happen here. And when the cold, hard facts seeped slowly into our consciousness, we were left desolate. There was nothing we could do but pray. The question was how to pray? Pray for what?

Denman of Wesley Methodist told how he took his two boys out of school and they stood on the parade route neat Love Field Airport to watch the motorcade go by.

When the car came into view, we were glad to see that it was an open car for it meant we would get a better view of the president and the First Lady. The car passed by so closely we could have almost reached out and touched it, and we had the thrill of seeing our president.

When the Denmans got to the Trade Mart, they encountered protesters and heard sirens. There was a “commotion” in the crowd and then they heard that the president had been shot. They went back to the car and listened to radio reports as they drove home.

As we traveled homeward, we continued to listen to the reports. The older boy asked that the radio be turned off, that he didn’t want to hear it. He didn’t want to hear that the president was dead. Before we arrived home, however, we knew that President Kennedy had died.

What should we do now?

In the days after the assassination, Dallas civic and business leaders tried to distance the city from the actions of Oswald, who was left-leaning and a relative newcomer to the area, but the clergy represented in the sermons did not do that, said SMU’s Wilson.

“I think clergy didn’t really want to echo that because they did not want to lose the opportunity for introspection that this tragic event presented,” he said. “I think that’s why you see some divergence between what political leaders said, which was to try to put arm’s length between the city and this tragedy versus what religious leaders did, which was to ask their congregations to search their souls about how even if they were not individually responsible in any meaningful way for this assassination, to see whether they harbored the kinds of spirit of hatred, intolerance that could lead to an event like this.”

Levi Olan

Temple Emanu-El’s Rabbi Olan, who had spoken on the psychological, ethical, legal and personal challenges raised by the assassination, said:

What should Dallas do now? For its psychological well-being it ought to accept blame and responsibility for its behavior and act upon that now. It is getting later all the time. Its moral climate needs some lifting up so that it can rise above the fourth level of values which determines all things by, ‘What is there in it for me?’ The church and synagogue are charged with the responsibility of talking to the people, not reflecting their present values. Perhaps to paraphrase the late president, our value system in Dallas ought to be, “Ask not what Dallas can do for me but what can I do for Dallas.”

Dickinson told his congregants at Highland Park Methodist:

There can be but one motive for conduct in our world. Civic pride is not enough. Protection of our economic interest is not enough. Recognition of God’s law and the response to his love is the only motive by which our actions can be justified.

The question, then, we face today is, What does a Christian do? What does a Christian do today in Dallas? What can we do who stood this morning to declare our faith in one God, Maker and Ruler of all things, Father of all men, the Source of all goodness and beauty, all truth and love? Such faith cannot be maintained within a vacuum. We either have faith and God, we either have faith in God, or we have no God at all.

Denman at Wesley Methodist called for repentance, beginning with himself:

This morning I am going to kneel here at the altar and ask God for his forgiveness. I am going to ask him to forgive me for my sloth, my love of ease, my selfishness, my prejudice, my pride and all that stands between me and a life lived for the glory of God and the redemption of a nation. I ask you to join me here. Do not come if you feel you have no need of repentance. Come only if God is calling you to repentance and if you in this moment want to pray: “God be merciful to me, a sinner; I have been part of the problem but by God’s grace from this day forward I will be part of the answer.”

Holmes’ charge to Northaven Methodist took a more civic turn:

By the grace of God, this much is clear. We are called to be a city where political debate continues. Different points of view must be expressed. Liberals and conservatives, Democrats and Republicans must go on exchanging partisan convictions. The two-party system is intrinsic to our way of life, and through the years the correctives, balances and checks of these two parties held in tension, have given depth and magnitude to our destiny as a nation and a people. But the context of that debate in Dallas — as across our land — must be the context of mutual forbearance and good will. We must be as jealous of another person’s right to think and live as we are jealous for that right ourselves. It is not too late for us to learn that men can agree to disagree in love and still hold partisan persuasions.

At the end of Holmes’ sermon manuscript, someone typed this postscript:

“Upon the conclusion of this sermon, Rev. Holmes was handed a note informing him that during the sermon Lee Harvey Oswald, alleged assassin, had been shot while being transported from the city to the county jail in Dallas, Texas. He then informed the congregation.”

Jeff Hampton grew up in Richardson, Texas, a northern suburb of Dallas. He is a freelance writer raised at First Baptist Church of Richardson and now a longtime member at Wilshire Baptist Church in Dallas.

Related article:

The Fifth Freedom: Freedom from Hate | Opinion by Jimmy Allen