Stereotyping young adults as lazy and entitled – and as a major source of the problems facing the modern church – may be easy but doesn’t come close to understanding this group of Americans.

Tim Clydesdale (Photo/College of New Jersey)

“The story is a lot more complex than that,” said Tim Clydesdale, a sociology professor at The College of New Jersey and co-author of the new book The Twentysomething Soul: Understanding the Religious and Secular Lives of American Young Adults.

The prevailing narrative that young adults are generally disinterested in faith and totally self-absorbed misses the truth by a wide mark, he said. The “Millennial” label has become a catch word for these stereotypes.

“We don’t use the generation terms” in the book, Clydesdale said. Materials and ideas supporting generational descriptions seldom rely “on robust research.”

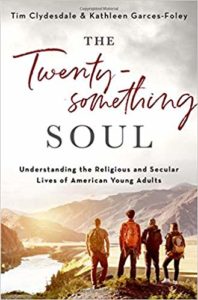

(Image/Amazon)

The research took him and religion scholar co-author Kathleen Garces-Foley about 10 years and delved into the complexities of life for today’s 20-somethings.

The authors examined the emerging realization among social scientists that it’s taking young adults about an additional decade than in previous eras to complete the typical markers of adulthood – such as living on their own, finding a long-term partner, beginning a career and having children. Trends in religious affiliation were also factored in, Clydesdale said.

“We write, therefore, to tell a story that is more optimistic than most,” the authors explain in the book. “We write to introduce readers to the full spectrum of American twentysomethings, many of whom . . . live purposely, responsibly, and reflectively.”

Clydesdale spoke with Baptist News Global about young American adults and the assumptions swirling around them. His comments are included here, edited for clarity.

What are the prevailing stereotypes about these young adults?

Some will use terms like “the lost generation” because it seems like folks are wandering, unable to find their way. Some use the phrase “kidults” and some say “extended adolescents” for people who don’t seem to have a clear sense of the path they are on, or who seem to be avoiding or delaying adulthood.

They also are considered the least religious group. Is that accurate?

In the book we demonstrate that among Americans in their 20s, 25 to 35 percent take their faith very seriously. That has remained remarkably stable. What’s changed is the people outside of that group. There was a time when they would have a social affiliation with religion – they felt they needed to have an affiliation with a church or synagogue to be a good American. That has shifted significantly. Those are called the nones. That group has grown significantly.

So, young adults aren’t all abandoning church?

Why a lot of people are confused about that is that young adults very much flock together. They do not evenly distribute across American houses of worship. They tend to self-select into congregations where there are a lot of other young adults. They like to attend worship services where there are other people like them.

And people who take faith seriously hope to partner up with someone else who does, so they’re not likely to go to a small congregation with 40 people. They want increased odds of finding friends and a romantic partner and that’s going to happen typically at urban congregations that are larger in size. Sometimes they are traveling long distances just to get there, passing dozens of churches that would be happy to have them.

The book includes chapters on mainline, evangelical and Catholic Christians. Are there significant differences between them?

There are differences. On the whole, the mainline Protestants have the lowest proportion of folks who we call “active” – who attend at least a couple times a month. Evangelicals have the highest rate of that. They consider attendance to be important and they consider spiritual growth to be very important in their lives.

What did you learn about the nones?

The smallest group of them are what we consider philosophical secularists, or who use the term atheist for themselves. More than half are theists – we call them unaffiliated believers. They clearly believe in some significant divine being, but they don’t have a church or other house of worship that they attend. We also have spiritual eclectics. They tend to pick up a little bit of spiritualty from a variety of different religions and fuse that into their own lives.

You state an optimism about these young adults in the book. Why?

For a couple of reasons. Once you really get a sense how much the economy and the culture has changed, making it harder to figure out life and to find a path to adulthood, that gives you a lot of empathy. A lot of jobs today are low-wage, low-skill or high-wage, high skill – and not a lot in between. To launch a career takes time. Then think about personal relationships, their love lives. Any given marriage has a 40-percent chance of ending in divorce. That’s made people a lot warier of marriage and intimacy. Wondering if they are with the right person takes longer. All these things keep getting harder and harder and housing hasn’t become cheaper anywhere, especially rental housing. When you put all that together I gain a lot more empathy. I see a lot of 20-somethings working really hard just trying to hold on.